GOMA Waterford

10 May – 8 June 2025

Street Art and Graffiti become radically transfigured once separated from their obligatory medium of the street, coming, in fact, to be something entirely other.1

Even for those energised by the intellectual stimulation that contemporary art offers, walking into a gallery of paintings can come as a relief. A good exhibition of paintings can provide not only a set of images to explore, but a point through which to access some meaning in a cacophonous culture.

David Fox’s first solo exhibition, ‘Urban Fingerprint’ invites us to be “the pedestrian who is for an instant transformed into a visionary.”2 However, rather than de Certeau’s ‘Icarian fall’, we descend to the mean streets by way of a sturdy, critical scaffold, created by Fox’s careful and consistent use of a reliable, pictorial language, derived from everyday manifestations of the modern state, which includes road signs and markings.

Each work is a self-contained verse in the larger story. Take Graff on James Street (2025) – a dull sky, strung by wire and etched with the body of a crane, broods over a junction, its lampposts, railings and signage a grid that is echoed in road markings, only relieved by curved tram tracks. Pinned within this matrix, cut out facades, crossed with supports, rise behind hoarding that is tagged with graffiti, white on black.

Modern graffiti – or ‘graff’ as the artist refers to it – evolved in New York in the 1970s as a “signifier of radical transgression but the days when we could celebrate graffiti and/or street art as a kind of resistance against the evil authorities are way behind us.”3 Fox’s contained use of it might represent the annexing of transgression by the voracious neoliberal state. ‘Graff’ is indeed truncated, now monotone hieroglyphs of futile rebellion.

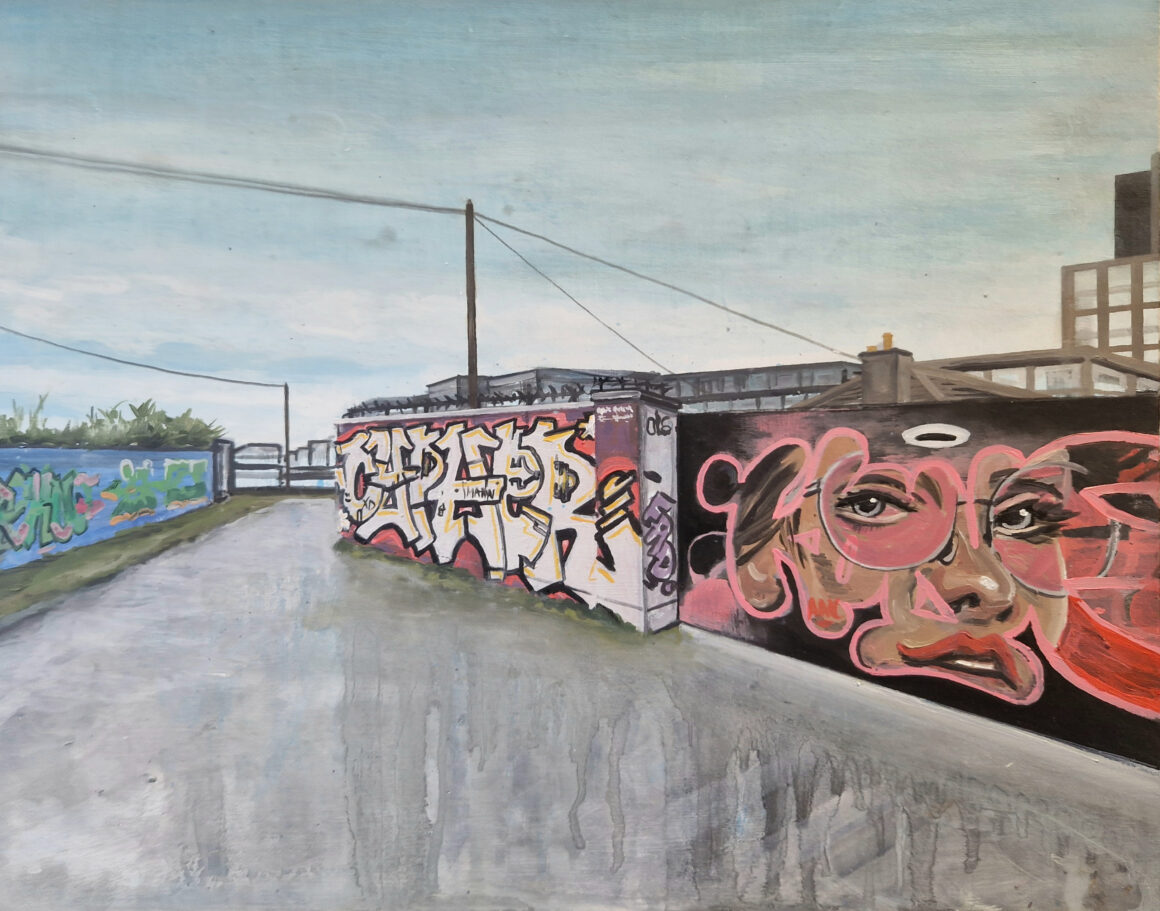

Fox’s centring of the ubiquitous mural – often state-funded – further underlines such a reading. Street Art, Rose Ln (2025), boxes off dreaming figures in a bland housing scheme, while the striking ‘raver’ tag in Raver Mural GCD (2023) is temporary and overlooked by a blind and defunct facade. The mural reframed reflects the systemic co-opting of the anarchic – a reminder that these days, street art is more often a signifier of gentrification.4

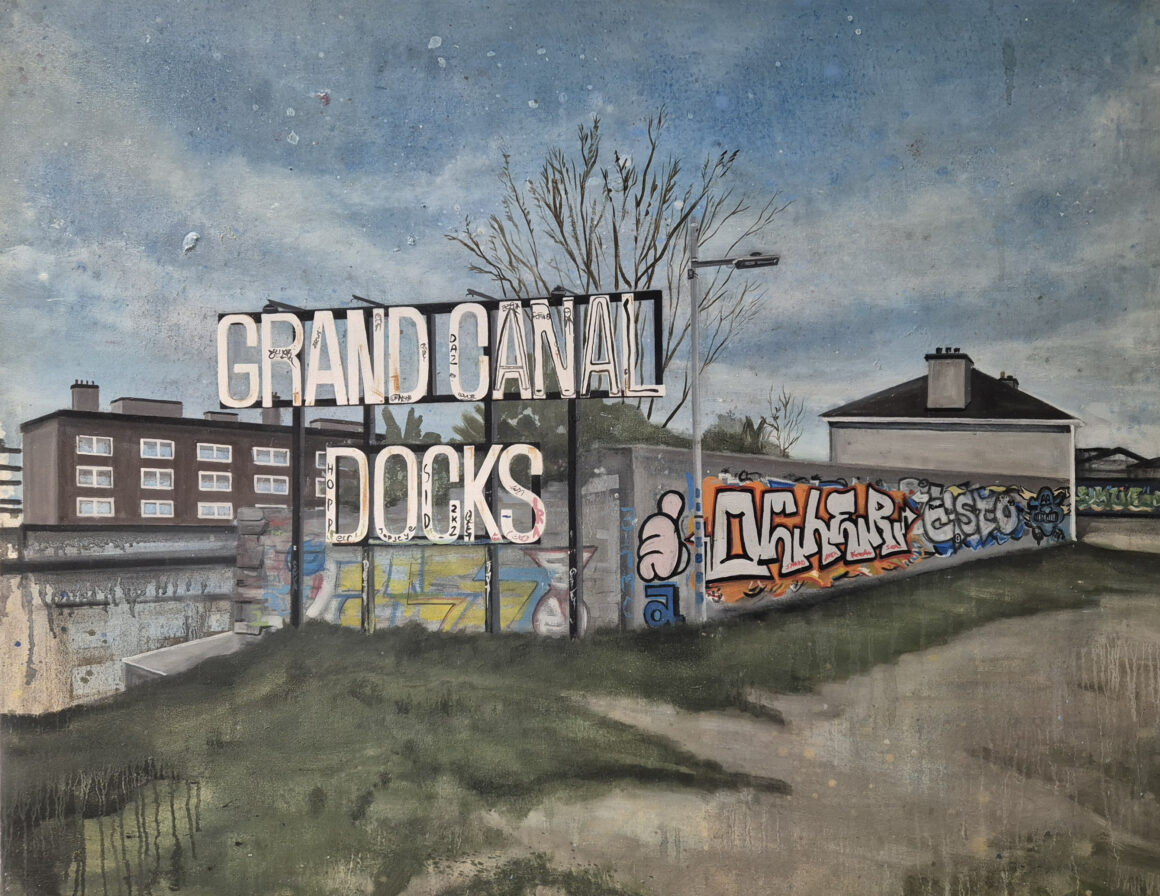

The use of text within the image supports this view but can also point to other tellings. In Grand Canal Docks (2024) – an area controversial for its accelerated development – the signage, looming large, is neglected, scribbled on, and offset by a wall of tagging. Behind it, mean little windows squint. In Graff on Chancery Street, the text on the ground, ‘Loading – Loading – Loading’, might be taken as a reference to the blizzard of digital imagery that acts to paralyse us, while a mural of a character from The Simpsons, featuring in Fat Tony (2024), doubles down with its hint of the televisual culture which keeps us stuck to the sofa. Furthermore, Parrot Mural Belfast, Fliadhais Mural, Ballina and Big Fish, Foxford (all 2024) could be seen as caricatures in our tense relationship with our environment, a distancing suggestive of malaise.

Still, there are hints of wildness and transgression; weeds sprout from chimneys, naked branches scratch the sky. The edges of the crumbling metropolitan scheme are both indicative of our huge impact on nature, and suggestive of how these environments might eventually respond.

Above it all are skies, some awash and speckled, others with wisps of impasto, but all are dull, even during summer in the stifling city. Below, in the drippy, dribbly ground, the artist allows some breathing space. The expansiveness of works like Street Art GCD, (2024), and Cat Mural, Waterford (2025) convey the joy of painting. There are traces of the artist’s previous evolution in Ulster Says Yeoo (2023), the mural here less like a depiction and more of a portrait, defined by the swoop of the yellow double lines and the retreat of graffiti to a fuzzy background.

The paintings in ‘Urban Fingerprint’ can be studied and enjoyed for their images alone, with the added bonus that the subject matter will be familiar to many. It is this familiarity – the entropic cityscape and the centring of street art within it – that allows us to consider the political, cultural and natural landscapes and where we might situate ourselves within them.

Clare Scott is an artist and writer based in Waterford.

1 Rafael Schacter, ‘The Ugly Truth: Street Art, Graffiti and the Creative City’, Art & the Public Sphere, Vol. 3, Issue 2, December 2014, pp.163-165.

2 Michel de Certeau, ‘Walking in the City’, The Practice of Everyday Life (University of California Press, 1984) p. 93.

3 Kurt Iveson, ‘Graffiti, street art and the democratic city’ in Konstantinos Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (Eds.), Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing, and Representing the City (London: Routledge, 2017) p. 89.

4 Schacter, op. cit.