SADBH O’BRIEN REVIEWS A CURRENT EXHIBITION AT IMMA.

Featuring over 40 Irish or Ireland-based artists, ‘Staying with the Trouble’ at IMMA feels especially important to the current moment. The exhibition is grounded in the research of Donna Haraway and is titled after her seminal text, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016).

A prominent figure in contemporary eco-feminism, Haraway offers reassuring perspectives on how we can respond to, and make sense of, troubling times. Where catastrophic events and seismic geopolitical shifts are triggering and can overwhelm us into inertia, Haraway gives us proactive methods to sit with, counteract, and think around these complex systems. Her expansive thesis conjures a biomorphic, multispecies space of storytelling, which denounces human exceptionalism and decentres capitalist viewpoints of the world.

This is a space of transmogrification in which genders and genres can be indeterminate, unresolved and of course, open to what she calls ‘Tentacular Thinking’. From this, the curators have used five propositions, as defined by Haraway: ‘Making Kin’, ‘Composting’, ‘Sowing Worlds’, ‘Critters’ and the ‘Techno Apocalypse’. However, strictly categorising each artwork into one of these is tricky, since most are multi-faceted and interwoven across multiple perspectives.

The first works encountered are rooted in a type of magic. In Kian Benson Bailes’s sculpture, Self Actualiser (2024), four spider-like creatures, playfully adorned with frills, phalluses, and bells, hang from coloured thread. Their knotted web evokes a playful and creative engagement – a woven dance. The multi-eyed faces are both mischievous and wise, evoking the supernatural, and alongside the small ceramic figurine, Weather Statue (2025), and textile creature, Archiver ii (2025), reflect the artist’s interest in folklore customs and craft traditions.

The theme of ‘Composting’ arises in Bea McMahon’s ‘low-tech’ biomorphic breathing sculptures, Ierse Stoofpot/ Irish Stew (2024). The paper structures are stained with organic matter, such as beetroot, turmeric, coffee, and cabbage – a potent concoction influenced by Macbeth’s witches’ brew. Earthly, human, and cyborg, the work’s continuous inflation and deflation is controlled by exposed mechanical apparatus. Aoibheann Greenan’s compelling film, The Ninth Muse (2023), combines moving image, performance, and sculpture. A witch-like husky whisper conflates sinew with cables, skin with plastic, creating a speculative narrative on techno-human experience. It highlights looped technological systems and sits at the intersection of neuroscience, techno-feminism, myth, and magic.

Storytelling is central to the proposal of ‘Sowing Worlds’, focusing on planting ideas, relationships and stories that can influence potential futures. Visually striking works by Samir Mahmood and Sam Keogh expand this allegorical approach with colourful, figurative scenes, informed by the Mughal miniature painting tradition and sixteenth-century Flemish tapestries, respectively.

Venus Patel’s enrapturing film, Daisy: Prophet of the Apocalypse (2023), confronts and dismantles the heteronormative and transphobic preaching of religious indoctrination. Patel plays a self-proclaimed transexual Texan preacher who is attempting to convert the public to an LGBTQ cult, baptising her followers, who emerge from biblical waters as hybrid queer creatures. In this way, Patel flips abusive anti-trans and homophobic sentiments back towards heteronormative constructs in a truly effective manner.

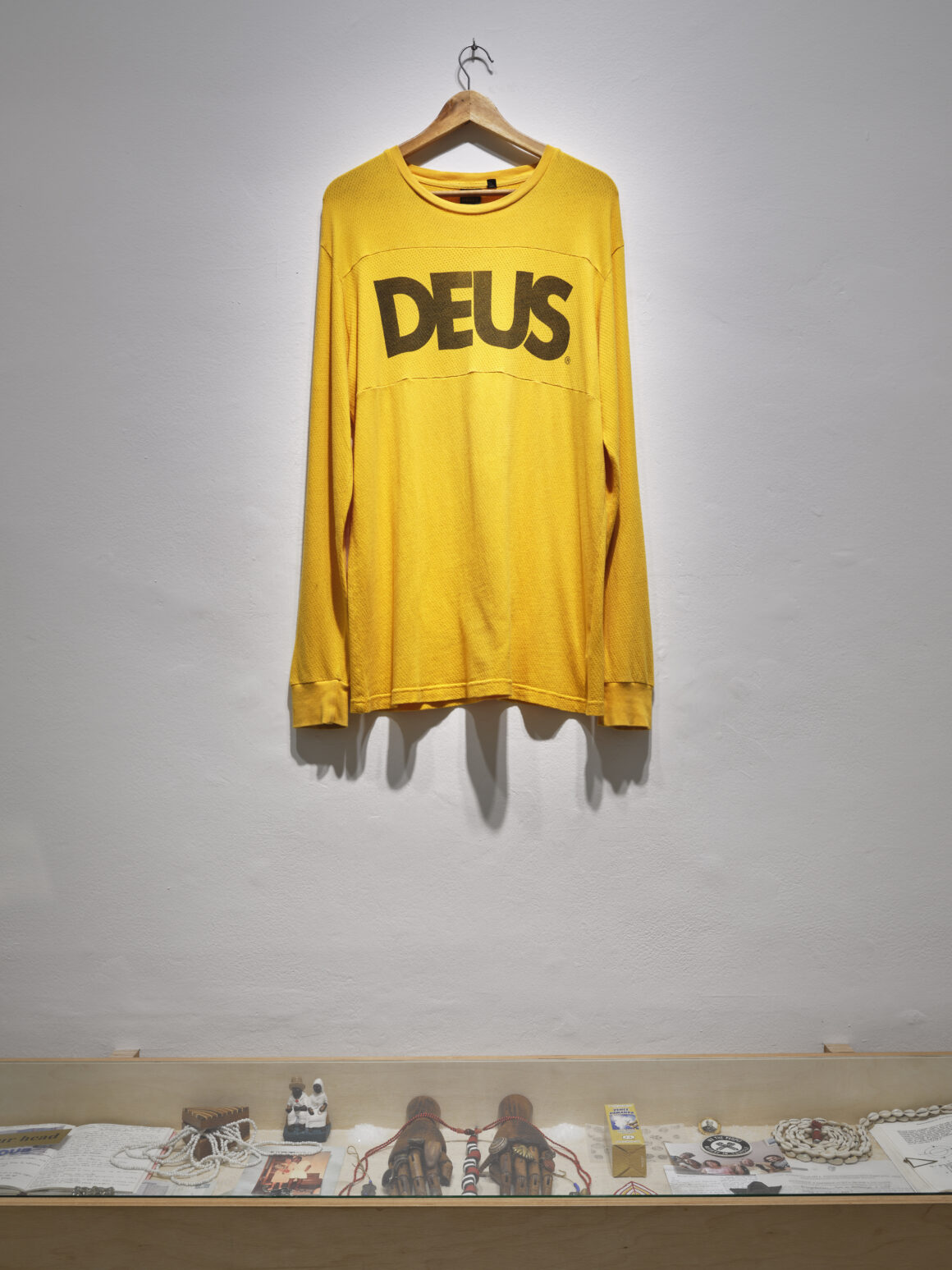

Companionship and cohabitation between the humans and non-humans that share this planet are central to ‘Making Kin’, which proposes forming bloodlines to other planetary organisms. Alice Rekab uses their mixed-race heritage to consider identity through familial connections across two distinct places. In nest of tables (Red): together in difference (2022), Rekab blends the domestic and familial to highlight the symbolic influence of animals within cultural history.

Given that agriculture forms part of Irish heritage and contributes significantly to the country’s economy, it’s unsurprising that several works deal with farming practices and its by-products. For example, Watchorn’s sculpture, Surrogate II (field) (2021), a bevelled block of beef fat and leather rosette, mechanically bolted by gate clamps to a weathered fragment of a shipping pallet, demonstrates the artist’s clever and intuitive use of materials. Here, a tension occurs between life, death, and the stark inhumanity of systems designed to extract maximum value from livestock.

McKinney’s Drumgold Holly Embryo Transfer (2021) is a curiously striking sculpture comprising a crescent-shaped, galvanised, steel cattle feeder, flipped on its side and weighed down by sandbags. Hanging from this is a brightly coloured sculpture, woven from artificial insemination straws. Inspired by a protective talisman, made from a bunch of holly found in a Wexford farm, the woven straws form clusters of berries, from which pointed cattle horns emerge. It calls to mind the very real grief and suffering in Andrea Arnold’s film, Cow (2021), showing the life of a dairy cow through the animal’s eyes, beginning with a heart-breaking postnatal separation. Like the film, McKinney’s work exposes stark systems of physical and psychological control, built into the engineering of farming apparatus, and questions the impact of bioengineering on our bovine counterparts.

Bridget O’Gorman also examines systems of power, specifically how civil infrastructure excludes those of us who have access or mobility issues. Highlighting a world rife with barriers, her installation, Support | Work (2023), forms a system of precarious, suspended pulleys, made from haphazard parts of mobility aids and fragments of mosaic flooring. The combination provokes a sense of phantom pain, as one imagines the brittle sculptures falling to the floor.

‘Techno Apocalypse’ draws on religion’s preoccupation with the end of the world; however, the presented works aim to variously subvert or dismantle end-stage capitalism. Both Austin Hearne and Luke van Gelderen focus on patriarchal systems of identity from a queer perspective. Hearne’s Curtains of Celibacy and Glory Box (both 2023) reference church interiors and confessionals, while alluding to institutional hypocrisy and oppression within the Catholic Church. Employing interior design techniques, including hand-painted wallpaper, the artworks subvert ‘divine’ authority by building an opulent, ecclesiastical den of secrecy and queer desire.

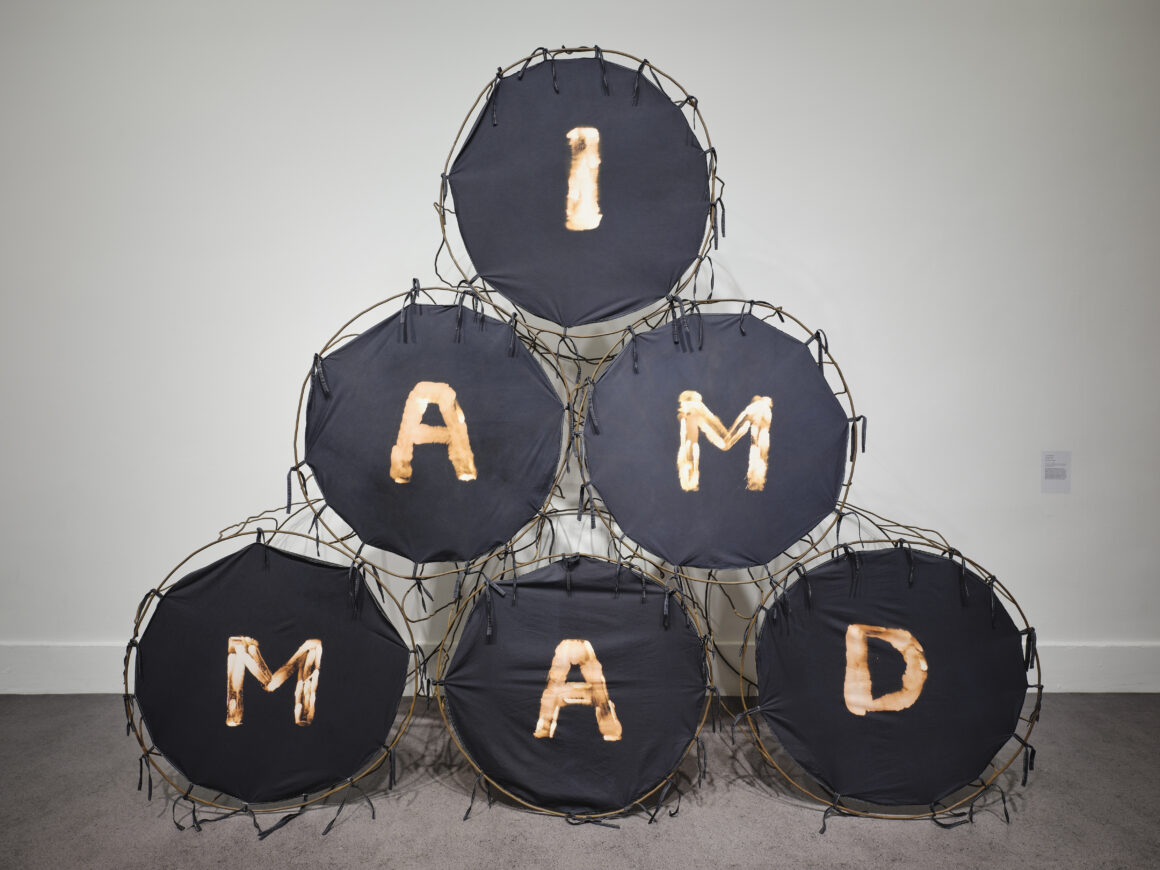

Van Gelderen’s film, HARDCORE FENCING (2023), examines the influential tropes of contemporary masculine identity emerging from digital culture and far-right politics. The film exposes the deep fault lines of insecurity, unpredictable anger, and violence – forces that have recently been seen on the nation’s streets. This is further evident in clips of riots, fires, and protests in Eoghan Ryan’s Circle A (2024). The film records a group discussing the term ‘anarchy’ and its role in contemporary society, unravelling its place within academia and lived experience in an increasingly polarised political landscape. In the face of accelerating global conflict, Diaa Lagan’s paintings offer reflection on political upheaval. Arabic calligraphy is laser-cut from Perspex, framing imagery of ancient Islamic architecture, designed for peace and tranquillity.

Continuing at IMMA until September, ‘Staying with the Trouble’ takes time for viewers to navigate, since the featured artists (too many to mention here) variously pull from complex material, digital, and metaphysical realms. Returning to Haraway’s argument for expansive ways of thinking about the world right now, the exhibition illustrates how humans are deeply woven into systems of interconnectedness, to which we have a profound and urgent responsibility.

Sadbh O’Brien is an artist and writer based in Dublin.