AENGUS WOODS REVIEWS A RECENT EXHIBITION AT SOLSTICE ARTS CENTRE.

Infinity is one of those rare concepts that does not so much pervade western thought as haunt it. Since the calculations of Dedekind, Godel and Cantor, we tend to think of infinity primarily as the concern of mathematicians. Yet, starting with Zeno’s paradoxes, going all the way to Hegel’s distinction between two forms of infinity, we see that its ability to create aporias and vanishing points within and without the fabric of reality has driven philosophers and artists to distraction for millennia.

‘Of Peras and Apeiron: ends and infinity’, the superb group show at Solstice Arts Centre in Navan (6 September – 25 October 2025), takes its title from the ancient Greek terminology. Aristotle notoriously relegated infinity to the realm of the potential (rather than the actual) in keeping with the classical world’s generalised fear of the infinite. The ancient Greek worldview prized order, proportion and clear delineations. Infinity, on the other hand, promised chaos and disorder, with yawning chasms lurking in the fabric of time. Infinity and its repercussions return and return, throughout the history of art and philosophy. The perspectival advances of early renaissance drawing, and the complex computations around modern quantum physics would be unthinkable without Cantor’s multiple infinities.

Nonetheless, despite its full embrace by modern mathematics, something of the Greek anxiety around infinity remains with us. Descartes claimed that it was the only concept that could not be produced by humans and must be seeded in our minds by God. Hegel, by contrast, argued that it is precisely the mind that is infinite. We, ourselves, would then be the very source of that which so de-stabilises us.

This odd tension between the concept and the mind, between system and individual, pervades this exhibition. Works by Ray Johnston, Gerald Caris, Ronnie Hughes and Neil Clements, at first glance, seem to be working within the legacies of minimalism and Op art. But these presentations are wonderfully deepened and enriched by the inclusion of a substantial number of works by Channa Horwitz, dotted throughout the exhibition. Horwitz, a remarkable conceptual artist who only achieved due recognition in the last years of her life, produced works based on complex numerical and spatial systems of her own devising. Her Rhythm of Line works, exquisite drawings on Mylar and utilising gold leaf, bring to mind Sol Lewitt, but they are executed with a delicacy and sense of colour that elevates them entirely to their own realm. Add to this her Sonakinatography compositions, dating from 1969 to 1996, expansive hand-written systems of numbers on graph paper. They are mysterious and suggestive, at once reflecting the focused energies of the scientist and the obsessive ruminations of the outsider artist.

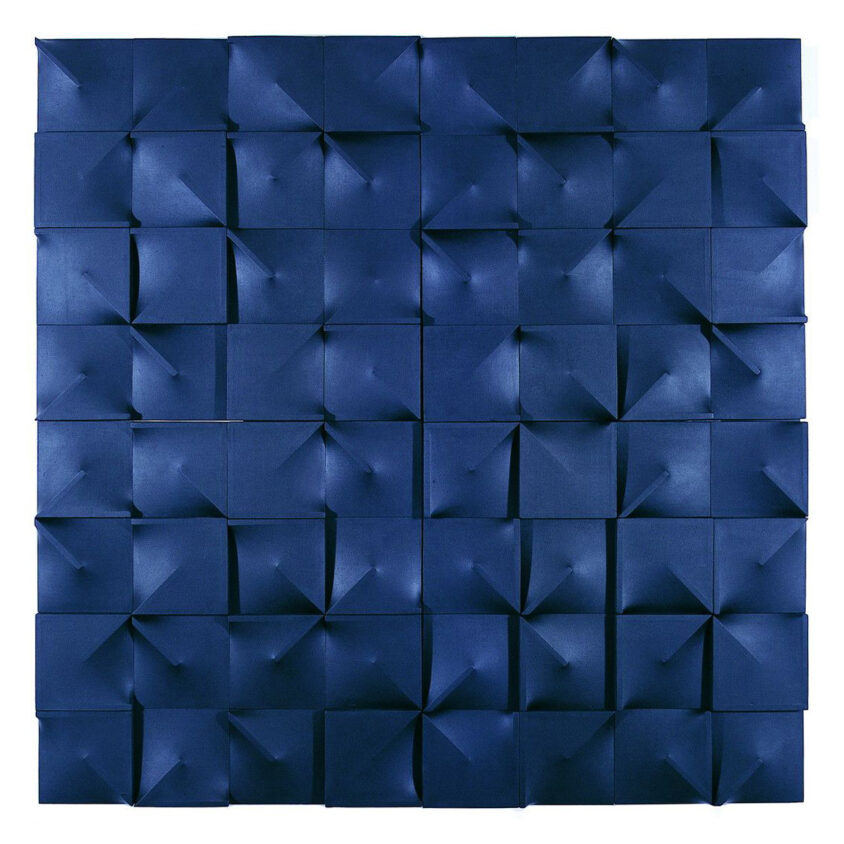

The Sonakinatography works are essentially scores; systems of notation to be interpreted at will by others. This intimate connection between system and practitioner, between the concept and the mind considering it, is key to Horwitz’s works, and in turn provides a connective tissue between the other artists in the show. Across the presented works, human touch grounds abstract complexities or provides the essential input for systems that might otherwise be detached from anything beyond themselves. Sixteen rotated forms (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) (1975) by Roy Johnston are a case in point. Each of the 16 units that from the individual work are composed of grey painted fabric, stretched over three-dimensional constructions, organised in shifting patterns. The austere and programmatic language of the work is, however, softened by its painterly sensibility and the tangibility of the artist’s touch.

Likewise, Ronnie Hughes’s paintings, at first glance, seem to represent complex geometrics of colour and shape. However, closer inspection reveals traces of the hand. The pull of the paint bears traces of brushstrokes; clusters of triangle and diamond, in their various undulations, point to long hours taping and tracing lines and shapes. Neil Clements’s clean, tight paintings are pleasingly rigorous but his choice of tread plate as a painting surface also points to the human life and labour underpinning their execution, and the art-historical intellectualism they evince.

The labour of the artist bleeds into questions of labour more generally in the works of Grace McMurray. Knitted objects, fabrics and woven materials draw parallels between aesthetic systems and those of social organisation and labour hierarchies. Made of painted and woven satin ribbons, We aren’t on the same wavelength (2022), by virtue of its abruptly fragmentary appearance, points to a system that is, at least in principle, both spatial and temporally endless.

The works of Dannielle Tegeder and Suzanne Triester share with Horwitz that inclination toward the obsessive that might be most optimistically taken as the human mind attempting to make sense of the sheer plethora of reality. Tegeder’s pieces feel richly symbolic. Conjuring ladder with handbook of one shape meaning, and Standard line, with Fixed Element (2024), in particular, seems totemic in its presentation of finely crafted patterns in painted wood, suspended, drawing the eye upward. Treister’s prints, in their invocations of Kabbalah and shamanism, reverberate with that other abiding association with the infinite: mysticism and the precise mechanisms of how the individual can, or indeed perhaps cannot, maintain themselves in the grand flux of being and time.

Overall, the show intriguingly brings to light the attractions and the challenges of system thinking, while dual notions of infinity permeate everything as creation and dissolution. Nonetheless, of the many minimalist, conceptual or systematic artists, hovering in the background of this show, none seems more pertinent than Agnes Martin. Her grids, lines and dots incessantly highlight the attractiveness of systems, to which the exhibiting artists are evidently in thrall. And while these systems can exceed and evade our control, extending ad infinitum, they can sometimes be tamed and shaped, at least momentarily, by the hand and the mind.

Aengus Woods is a writer and critic based in County Louth.

@aengus_woods