CLODAGH ASSATA BOYCE INTERVIEWS BEULAH EZEUGO, CURATOR OF TULCA FESTIVAL OF VISUAL ARTS 2025.

Clodagh Assata Boyce: TULCA Festival of Visual Arts 2025 is titled Strange lands still bear common ground. Can you explain why you chose this title?

Beulah Ezeugo: I chose this title because I enjoy a statement that can gather its own kind of energy. I also enjoy the trend of past editions of TULCA that lean into the poetic by using longer, slightly awkward titles. When a phrase is repeated enough, it can act like a shared refrain that shapes a shared language for that moment in time. This feels suitable for something as quick and celebratory as a festival.

The words in this title carry ideas that conjure very specific definitions that shift based on where you ask and who is speaking: the strange, the common, the land. When I am in Galway, the presence of the Atlantic feels significant. So, conceptualising the festival began with thoughts about Galway’s mercantile past, but also with the discourses taking place around migration now. Both of which make me wonder how arrival is felt on an island – a place that can feel protected by distance yet also vulnerable to outside forces.

Earlier on, I came across an image of a medieval Burmese Map of the World. It depicts a teardrop-shaped island rising from the ocean, with smaller islands drifting below, detached from the mainland. Where the image shows up online it is captioned something along the lines of ‘The Himalayas are shown by a horizontal green line: above is the magical land of seven lakes and Mount Meru; below is where strangers come from.’ It suggested that to know the world is to expect strangeness, and that this encounter is not only inevitable but also vital. We meet the world through others, and in that sense, we are all strangers to someone else.

CAB: This exhibition sets out to chart new ways of relation. Can you tell us a little bit about how this cartographical approach has shaped your curatorial and exhibition-building choices?

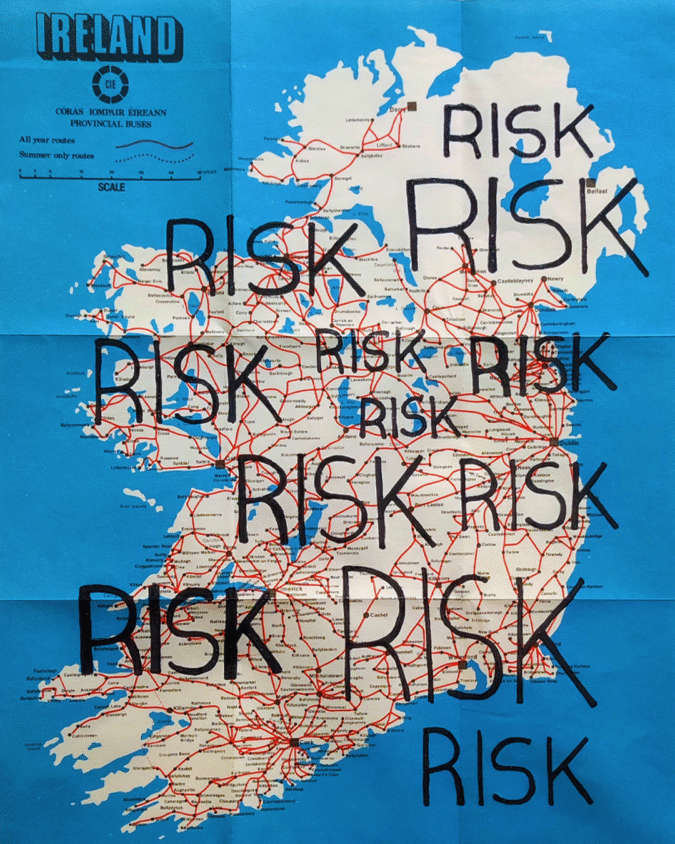

BE: Maps and borders hold a decisive place in contemporary art. For this exhibition, I was drawn to their paradoxes. Maps have long served as instruments of colonial power, but they can also act as anti-colonial tools, capable of encrypting, concealing, and revealing the limits of hegemonic knowledge.

In the curatorial process, I approached exhibition-making as a form of map-making: a search for pathways, a desire to document encounters, a projection of curiosity and intention across discrete spaces, and a pursuit of familiarity with the unknown alongside a willingness to be transformed by it. The exhibition follows this impulse, inviting audiences to navigate the worlds presented by the artists with openness and attentiveness.

The festival also borrows from cartographic methods to define its guiding themes. Much of the work begins from a specific historical or cultural vantagepoint and then from there, documents situated encounters with land, the sea, the creature, the stranger, and so on. So, re-orientation became a central theme and is understood as the act of unsettling assumed stances, turning again, and opening the possibility of encounter and contact.

CAB: How do you see the role of ‘the other’ and what is the role of art in shifting that?

BE: By evoking the idea of ‘the other’ I am evoking the ways of knowing and experiences that have been pushed aside or ignored by the dominant systems of power. The margin can also be an advantageous position. If every margin is someone else’s centre, then the task is to keep shifting our point of view toward the many centres that exist, noticing what becomes marginal from each new vantage point. Much of the work in the festival is a relational encounter with a powerful external presence, whether another person, another state, a non-human species, a mythical or spiritual figure. At times, the work itself shifts perspective from the margins, moving through overlooked or excluded positions to open new ways of seeing and being.

Although art has the capacity to propose new considerations and ways of seeing, at the same time, it’s difficult to think of how exactly contemporary art makes significant shifts. I am aware that a festival, no matter how ambitious, cannot do that much. What it can do is create proximity and enable an artist or an audience into intimate relations with an idea, and then hopefully spark the impulse to act in a different way.

CAB: What can audiences expect from this year’s festival?

BE: The festival includes a performance, artist talks, various exhibitions in Galway and one in New York, a book, and several audio works shared online and broadcasted over radio. There are many films in the programme that move fluidly across different geographies, as well as cultural and historic points. I am particularly excited to share Kate Morrell’s film …Y el barro se hizo eterno (…And the Mud Became Eternal) (2021), which explores ‘guaquería’, a type of political resistance that involves excavating the earth to loot archaeological treasures and indigenous cultural property.

I also look forward to the festival’s ephemerality. Many of the works are ongoing or exist as part of a larger continuum, so work in different states of completion will be able to converge and momentarily come into conversation with others. Marie Farrington’s Diagonal Acts (2025) appears here in its fourth, site-specific iteration, engaging with Galway’s Geology Museum and the knowledge embedded within it. There is also new work by Bojana Janković and Nessa Finnegan that brings together a living archive, related to crossing Ireland’s north-south border – a project that will continue to evolve during the festival and beyond.

CAB: Can you tell us about the accompanying publication?

BE: The publication extends the festival’s core questions around contact and proximity. It brings together several writers who explore the politics of place through poetry, prose, and experimental forms. Some of the writers involved in the festival also contribute to the publication, for example, the broader themes around Ireland’s revolutionary potential, presented in Caroline Mac Cathmhaoil’s film, Mirror States (2025), are extended through the publication in a more intimate register. Other contributors share writing that is rooted in research as well as personal experience, which reflect on how lived histories and places intersect. The publication includes responses to a range of environments, with particular attention to architectural and natural landscapes.

CAB: To what extent does international collaboration play a critical role this year?

BE: Through the open call, the festival emphasised collaboration and cross-border exchange – not to showcase a particular kind of work, but to create conditions for a certain type of exchange. In much art-making, the focus is on the final outcome or exhibited work, so the life of thinking and making, including the negotiations and the frictions that led to it, often remains invisible. Artists who work collaboratively are especially compelling because of their ability to establish through shared systems that support this way of working. Considering global interconnectedness felt particularly important, in order to invite reflection on the kinds of relationships that sustain solidarity and those that do not.

Some of the festival’s collaborative duos were already established, while others developed through the open call or expanded from individual practices. Mair Hughes, who has been exploring dual identity through excavations along the Welsh border, began with a solo project but invited collaborators Emily Joy and Durre Shahwar, who are now contributing artists in their own right. Peter Tresnan, a painter based in New York, has created a project which explores diasporic identity, drawing connections between Galway and New York. This has led to a secondary outpost of TULCA; an exhibition at 334 Broome Street in New York, organised by Peter, which will feature his work alongside contributions from other TULCA artists, and local artists working within similar themes.

Clodagh Assata Boyce is a Dublin-based independent curator and artist, who is influenced by the radical traditions of Black feminist thought.

bio.site/Clodaghboyce

Beulah Ezeugo is curator of the 23rd edition of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, which takes place across venues in Galway City from 7 to 23 November.

tulca.ie