ÁINE PHILLIPS REFLECTS ON TULCA FESTIVAL OF VISUAL ARTS 2018, CURATED BY LINDA SHEVLIN.

A person in complete accord with their environment is described as being in a ‘syntonic state’. Curated by Linda Shevlin, this year’s edition of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts in Galway examined this concept. The artists, thinkers and writers assembled by Shevlin offered different perspectives on this theme, generating various possibilities for viewers to attain syntonic experiences through art.

A vibrant example of human and environmental accord was created on the opening night by Aoibheann Greenan with The Life of Riley. Taking the form of a street procession, led by a lone piper, the work involved a number of Galway buskers, who entertained the crowds, alongside the artist and her cast of performers, animating the nighttime city streets and leading the audience from the festival gallery to the club. Greenan’s performance incorporated wildly embellished, hybrid costumes and props that mingled elements of Irish and Mexican visual motifs. Darkly funny, bizarre and congruent with Galway’s street performance culture, the event also presented a contemporary take on histories of the Great Famine period, a subject in Ireland deserving of new modes of analysis and interpretation. Video documentation of the performance was later presented to great effect on the top floor of the Fishery Watchtower Museum, a unique Victorian building that houses a collection of fishery memorabilia and vintage photographs.

TULCA was originally initiated 16 years ago, by Galway artists and curators, to counter the distinct lack of visual art spaces and resources in the city. This deficiency unfortunately persists, with space now at a premium, in the run up to Galway 2020; however, TULCA continues to enliven empty venues with contemporary art each year. Columban Hall, a former Congregational church, was theatrically lit to produce a unifying sense of anticipation and discovery. Helen Hughes commanded the space with her series of collapsed inflatable forms, deluged with paint, like extravagant mollusks or the discarded parts of an alien apparatus. Both Laura Ní Fhlaibhín and Rosie O’Reilly’s installations were complex narrative works involving multiple elements, correlating with each other to give the impression of an uncommon museum.

Another repurposed space, the festival gallery at Fairgreen House, displayed ‘Empathy Lab 2018’, a series of paintings by Colin Martin exploring ambiguous sci-fi subjects betraying modernist futuristic fantasies. Martin’s realism utilises a calm and banal painterly execution, to chilling effect. Robot children and cyberphobic computer banks assert the future is now and it is sufferable. Conor McGarrigle’s #RiseandGrind gave the opposite impression. His ordered algorithmic systems of thought, manifested across interconnected screens, seemed beyond human apprehension and tolerance. Denis McNulty’s video installation, David (Timefeel), featured the music and animated stills of a fresh-faced Bruce Springsteen, trapped in an endless recursive edit.

An exquisite contradiction to these restrained works was Stella Rahola Matutes’s Babel, teetering upright pillars of shimmering borosilicate glass. Invigilators hovered nearby to defend the delicate baroque shafts from the vibration of viewer’s footfall. This building has a vast underground concrete edifice, which was occupied by Jesse Jones’s Zarathustra, cinematic documentation of the Artane Band performing in an abandoned Ballymun swimming pool, wistfully redolent of failed housing projects in Dublin’s recent past. The bleak chamber was haunted by the notorious past atrocities and abuses perpetrated on the children of the original Boys Band, part of the Artane industrial school.

As explored in much of the works included in Shevlin’s edition of TULCA, the ‘syntonic’ also evokes sensations of longing for previously experienced states of harmony or oneness with our surroundings. Nostalgia and a yearning for an idealised past or future, was succinctly expressed in Cities of Gold and Mirrors (2009), the work of Cyprien Gaillard installed in 126, Galway’s artist-run gallery. This 16mm film has the aura of seductive lost worlds. A mirrored tower block dissolving in a controlled explosion, and the sun-drenched rutting contests of young men, provided haunting metaphors for evanescent desire.

In syntonic accord at the Electric nightclub, Mark Leckey’s 1999 cult film, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, used found footage to show the evolution of Britain’s nightlife, from Northern Soul and disco to rave culture. Joanne Laws also developed this theme with her text for the festival’s catalogue, which presented an ethnography of rave culture, rooted in her lived experience. She writes memorably that “when returning to a place where I’ve previously spent a lot of time, I half expect to see ghosts of myself in the street, going about everyday business”.1 These phantoms of place and identity were further elaborated in Bassam Al-Sabah’s newly commissioned CGI film work and sculptural installation, Wandering wandering with the sun on my back (2018), at NUIG Gallery. The film features a shimmering young man, trapped in a series of bizarre architectures located in dystopian, desert-like landscapes. Reminiscent of computer game aesthetics, the film implicates the viewer in the protagonist’s struggle to endure traumatic displacements, amidst transcendent, hallucinogenic transformations.

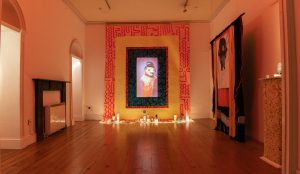

Galway Arts Centre’s ground floor collocated the vibrant neo-fauvist-style paintings and shrine-like banners of Eleanor McCaughey, in her multipart work, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed. In close proximity, Gavin Murphy’s wall installation and narrative video explored the material and cultural histories of the now-defunct Eblana Theatre at Dublin’s Busáras. The work captured fading aspirations of the modern Irish state to locate public memory in our past fantasies of social organisation. Upstairs in the centre, Paul Murnaghan tethered a blackened inflatable island to a heavy weight, under a relentlessly blowing fan, a sad and funny tableau in contrast to Marcel Vidal’s pitch-black colonnades, which incorporated petrified deer hooves and hardware materials, implying a sadistic but satirical violence.

Ciarán Óg Arnold showed the intriguingly titled photographic series, I went to the worst of bars hoping to get killed, channeling Wolfgang Tillmans’s sentiment that “only when you are aware of how tragic life can be, can you also enjoy the depth of a party through the night”.2 Other works at the centre were Ciara O’Kelly’s dual-screen video installation, which uses the promotional languages of corporate advertising, with slick humour and elegance. Susanne Wawra’s photo-transfer paintings, based on personal archives from her childhood in East Germany, were suggestive of the dim and aching memory of lost social realities.

TULCA events this year included a ‘Nostalgic Listening Club’ with Mark Garry, where participants honoured and shared beloved music collections, housed across old and defunct formats, such as cassette tapes, vinyl, gramophone discs and CDs. The Domestic Godless returned to the city soon after a GIAF residency, resuming their crusade to bring flavoursome tastes to celebrate and expand the culturally and historically entangled relationship between society and food. Collaborating with Deirdre O’Mahony in Mind Meitheal, along with EU research centre, CERERE, they presented new imaginings for a ‘heritage cereal renaissance’. Giving material form to this project, Sadhbh Gaston’s emphatic embroidered fabric banners were installed in Sheridan’s on the market. In addition, British writer and journalist Owen Hatherley spoke to Declan Long about his new book, Ministry of Nostalgia, described as a “stimulating polemic” against “austerity nostalgia”. This was followed by a screening of the radical documentary HyperNormalisation by British filmmaker, Adam Curtis, which was introduced by Conn Holohan.

In all, TULCA 2018 provided a rich mix of speculative viewpoints on syntony – a state that seems difficult to attain in modern life, as evidenced by the disconnect we currently manifest, in relation to our ecological and political environments. Clearly, a syntonic state is something to aspire to.

Áine Phillips is an artist based in County Galway.

Notes

1 Joanne Laws, ‘Feed Your Head: The Speculative Futures of Rave’, TULCA 2018 catalogue essay.

2 Wolfgang Tillmans quoted in Ha Duong, ‘Photographers Who Captured the Ecstasy and Abandon of Rave Culture’, 7 September 2018, artsy.net.

Image Credits

Mark Leckey, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999, video installation, Electric; photograph ©Jonathan Sammon, courtesy TULCA Festival of Visual Arts.

Jesse Jones, Zarathustra, HD film, installation view, Fairgreen House; photograph ©Jonathan Sammon, courtesy TULCA Festival of Visual Arts.

Eleanor McCaughey, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, 2018, installation view, Galway Arts Centre; photograph ©Jonathan Sammon, courtesy TULCA Festival of Visual Arts

‘Nostalgic Listening Club’ with Mark Garry, 10 November, The Mechanics Institute; photograph ©Jonathan Sammon, courtesy TULCA Festival of Visual Arts