Luan Gallery, Athlone

17 September – 16 November 2025

What systems are armed against us and how can we defend ourselves? This is but one of the many urgent questions raised in Luan Gallery’s latest exhibition, ‘System Arming’. The title is taken from the technical term for activating an electronic security or monitoring system – highly appropriate for an exhibition featuring artistic practices that focus on digital technologies and surveillance systems. ‘System Arming’ also serves to signpost the viewer towards ‘systems aesthetics’ as a critical framework for engaging with the exhibition.

‘System Arming’ was formally launched on 20 September by writer and academic, Dr Francis Halsall, who has contributed enormously to understandings of systems aesthetics as a relevant critical tool for contemporary art, including digital art. Drawing on information science and biology, systems aesthetics highlights the shift from the modernist belief in the self-contained art object, to a post-formalist focus on process, and the relationship between objects within systems.

American writer and critical theorist, Jack Burnham (1931–2019), was an early exponent of systems aesthetics for the analysis of art practice emerging in the 1960s and 1970s. In an essay for Artforum in 1968, Burnham stated that: “Art does not reside in material entities, but in relationships between people and between people and the components of their environment.”1 Almost 60 years later, Burnham’s assertion deeply resonates with the artworks presented in this exhibition, all of which have process-driven and relational components, highlighting the relationship of art to an ever-more digitalised world.

Nadia J Armstrong’s intriguing installation, GIRLHERO (2025), in common with her video, EDIFICE UNBOUND (2022), is a fantastical work of the imagination. It uses a range of digital and analogue systems to create what the artist calls the ‘quantum imaginary’. Combining the antiquated and the futuristic, her sculpted artefacts, made for this exhibition, are ‘protected’ by bell jars, or what were called ‘glass parlour domes’ in the Victorian era. This adds both humour and temporality to her presentation, as well as, possibly, a subtle art-historical reference to the ‘real time systems’ in the pioneering work of systems artist, Hans Haacke.

Interactive systems are in evidence in Aisling Phelan’s work. Her visually compelling film, Goodbye Body (2024) explores themes of identity and the possibility of transformation and shows the artist’s practice of creating processes using advanced technologies. Phelan creates digital versions of herself and other people and invites the viewer to interact with them. She thereby sets up a system of relationships between object, process, and spectator. With the mixed-media installation, Spares & Repairs (2024) the artist enquires further into the territory of transhuman possibilities.

The artist duo Kennedy Browne’s expanded installation, Real World Harm (2018), is another exemplar of a systems aesthetic process. By incorporating interconnected audio and visual systems and wide-ranging research, Kennedy Browne expose the sinister world of technofeudalism – a term developed by key thinkers like Greek economist, Yanis Varoufakis, to refer to digital capitalism as a modern economic system of control. Elements of this complex and multi-layered presentation include: Max Schrems’ Retrieved Facebook data (2018), a five-channel sound installation; a black vinyl mat used by the artists to present a series of ‘digital self-defence’ classes; and a wall-mounted guide to the video. The work also comprises text that has been laser-etched onto an Oculus Go VR headset, used to experience the 360-degree video. The overall effect is powerful and disturbing.

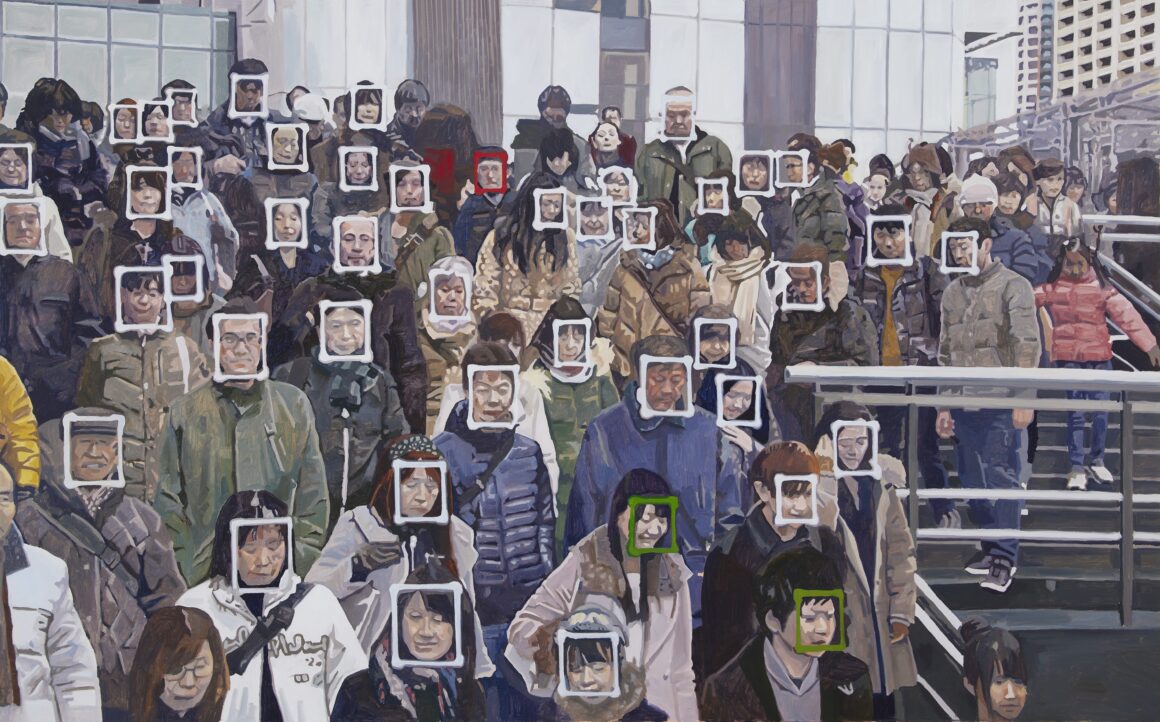

The inclusion of a substantial body of recent paintings by distinguished artist, Colin Martin, is an affirmation of the visual power of figurative painting. Yet, Martin’s paintings go well beyond the purely representational, and are underpinned by his process of research, using primarily digital sources. In this way, the paintings do not exist in isolation but are linked to other ‘objects’ and systems. Martin’s exploration of cybernetics and digital systems in his paintings sits comfortably within the exhibition and shares thematics and processes with the other artists. Recurring themes include state surveillance, both contemporary and historical. Martin’s oil paintings on canvas make for engrossing viewing. The artist uses a limited palette, with grey predominating, thus adding a sense of alienation and oppression. Among the works on show are the unsettling, though strangely beautiful, Robot (Anthromimetic) (2021) and the vertiginous Procedural City (Zorn Palette) (2025). Martin’s richly detailed paintings powerfully convey the precarity and anomie that comes with life under techno-oligarchy.

With ‘System Arming’, Aoife Banks has curated an expansive and multifaceted exhibition that challenges the cultural complacency arising from the ubiquity of technology, and, most significantly, situates artistic imagination at the frontier of digital resistance. It is an achievement that has profound relevance for a digitised world.

Mary Flanagan is an art writer and researcher based in County Roscommon.

1 Jack Burnham, ‘Systems Esthetics,’ Artforum, September 1968.