JASON OAKLEY’S INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL WARREN WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE SSI NEWSLETTER IN 1996.

In the first of a series of interviews with distinguished Irish sculptors, Michael Warren, a maker of dignified and spartan forms, talks about his working disciplines and the self-imposed limits of his practice.

Jason Oakley: I’d like you to talk, first of all, about your work in the outdoors, where I think some of your key concerns of rootedness in place and natural forces like gravity, are very apparent.

Michael Warren: Yes, I have a great interest in making outdoor works. A characteristic I like is that it’s work for someone – work with an audience in mind. Chances are, someone is inviting the work, be it the mayor, local authority, an architect or a developer. With public money involved there is an obligation on the part of the artist not to be too obscure – to provide entrance points. In addition, there are strict limitations and curtailments which I find very challenging: a given location may dictate horizontal treatment or verticality – the range of appropriate materials will be limited – history of place and function are likely to be considerations. Then there are matters, that depending on one’s temperament, one can find a challenge or hindrance, such as the teamwork, site control and general diplomacy which are part and parcel of any big project. Of course, all of this isn’t worth two hoots if the artist doesn’t instil his or her own creative integrity and personal preoccupations – it’s a multi-levelled process, a dialogue. Too much twentieth-century work is a case of the artists working in a bubble. When so much explanation has to be joined onto artwork, there is something very wrong going on.

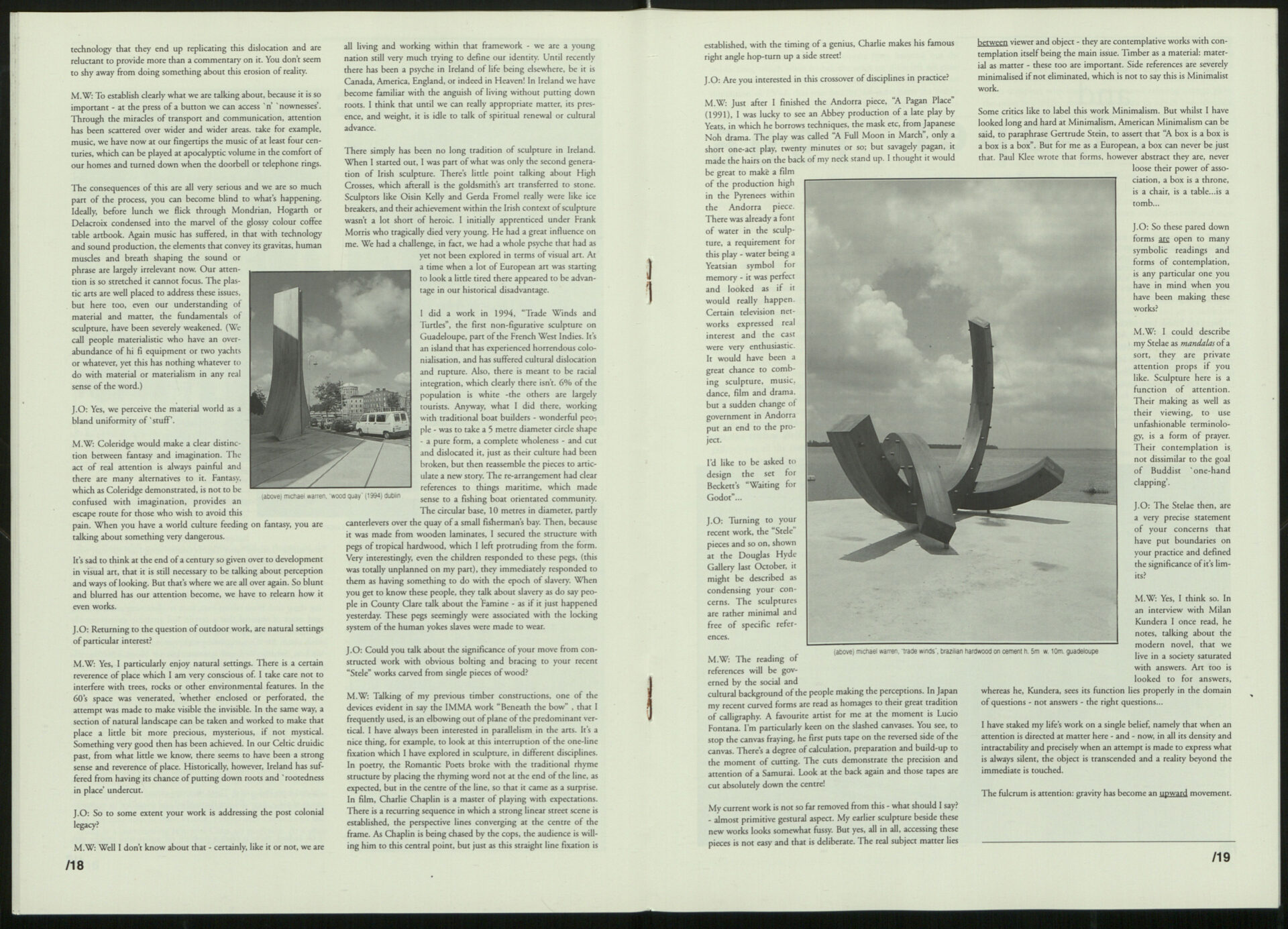

J.O: Your piece at the civic offices at Wood Quay is a good example of working to such constraints.

M.W: In that particular instance, I worked in close collaboration with the architect Ronnie Tallon. The verticality and scale of the work was determined by the building. A big consideration was of course the juxtaposition of the sculpture to the strict undercut form of harvested cedar, which was a nice foil to this, while the work’s base, 17 metres of white limestone, was a horizontal that had to be established.

J.O: And there are a number of obvious entry points to the work, such as the shape of the river at that point, a Viking longship…

M.W: If you go to the top floor of the building, where the planning offices are, you can see clearly the echo in the shape of the river, the bridge and the dome of the Four Courts. Much controversy surrounded the site with the Viking excavations: the work had to be a reconciliation of place past and present. As a new and important centre of civic administration, it needed a certain seriousness of intent and dignity. But to mark the full sense of place, it could not be forgotten that historically the Viking longships came right up the Liffey to this point. I took measurements from Scandinavian excavated longboats, the dimensions across the bow are replicated in the width of my sculpture. If you look at the sides of the sculpture, each laminate is uniquely tapered, feathered and fitted like the prow of a longship – tedious work!

J.O: To what degree do you find curtailments stimulating? Is an idea of limit important in your studio practice?

M.W: As I say, I find such public situations a tremendous challenge; I really look upon each new project as an adventure. In fact, I do not find any conflict between my more intimate scaled pieces and the public works. There is a clear common denominator – a common thread throughout. In both cases limit takes the form of a gravitational force. My indoor work could be taken as one continuous meditation on space and gravity. Activity takes place solely towards the bases of the work, with the descending vertical forms suddenly undercut at the last minute: the work has to be read downwards.

J.O: In this respect, I would regard your work as making a fairly significant step in terms of the history of sculpture. Most accounts centre on ideas of the sculpture freeing itself from the plinth, and perhaps gravity, to expand into a wider spatial realm.

M.W: From an art historical angle, I, like many students during the late 60s and early 70s, looked very closely at the discoveries of the Russian Constructivists. I later named my home and studio “Letatlin” after Tatlin’s famous aeroplane, the title combining his name with the Russian verb ‘to fly’. (In retrospect, I would have been better advised to call it Witsend or Taj Micheal!) The whole raison d’etre of Constructivists like Rodchenko and El Lissitzky was to elevate the mass. But we are talking about such brave talents here, such revolutionary understanding and usage of material, that a certain soil aesthetic unintentionally clung on to their spiralling shapes. I consciously combined my enthusiasm for Constructivism with my reading of philosophers such as Simone Weil and systematically set about inverting this thrust, replacing elevation of mass for its contrary. I needed to give anchorage and ‘here – and nowness’ to the work. That sense of ‘nowness’, presence and immediacy are vital issues in my work.

J.O: A lot of sculptors are dealing with this in the very broad sense of uncovering the social and cultural meanings of space; how does your work relate to this?

M.W: There is, I believe, a kind of innocence of perception that has vanished. In Medieval times, ceremonial costumes of heraldry registered like a trumpet call. We on the other hand are saturated with colour, form and sound. These, our very capacity for attention, our sense of place, have all been diminished and trivialised by technology.

J.O: Returning to the question of outdoor work, are natural settings of particular interest?

M.W: Yes, I particularly enjoy natural settings. There is a certain reverence of place which I am very conscious of. I take care not to interfere with trees, rocks or other environmental features. In the 60s space was venerated, whether enclosed or perforated, the attempt was made to make visible the invisible. In the same way, a section of natural landscape can be taken and worked to make that place a little bit more precious, mysterious, if not mystical. Something very good then has been achieved. In our Celtic druidic past, from what little we know, there seems to have been a strong sense and reverence of place. Historically, however, Ireland has suffered from having its chance of putting down roots and ‘rootedness in place’ undercut.

J.O: So, to some extent your work is addressing the post-colonial legacy?

M.W: Well, I don’t know about that – certainly, like it or not, we are all living and working within that framework – we are a young nation still very much trying to define our identity. Until recently there has been a psyche in Ireland of life being elsewhere, be it in Canada, America, England, or indeed in heaven! In Ireland we have become familiar with the anguish of living without putting down roots. I think that until we can really appropriate matter, its presence, and weight, it is idle to talk of spiritual renewal or cultural advance. There simply has been no long tradition of sculpture in Ireland. When I started out, I was part of what was only the second generation of Irish sculpture. There’s little point talking about High Crosses, which after all is the goldsmith’s art transferred to stone. Sculptors like Oisín Kelly and Gerda Frömel really were like ice breakers, and their achievement within the Irish context of sculpture wasn’t a lot short of heroic. I initially apprenticed under Frank Morris who tragically died very young. He had a great influence on me. We had a challenge, in fact, we had a whole psyche that had as yet not been explored in terms of visual art. At a time when a lot of European art was starting to look a little tired, there appeared to be advantage in our historical disadvantage.

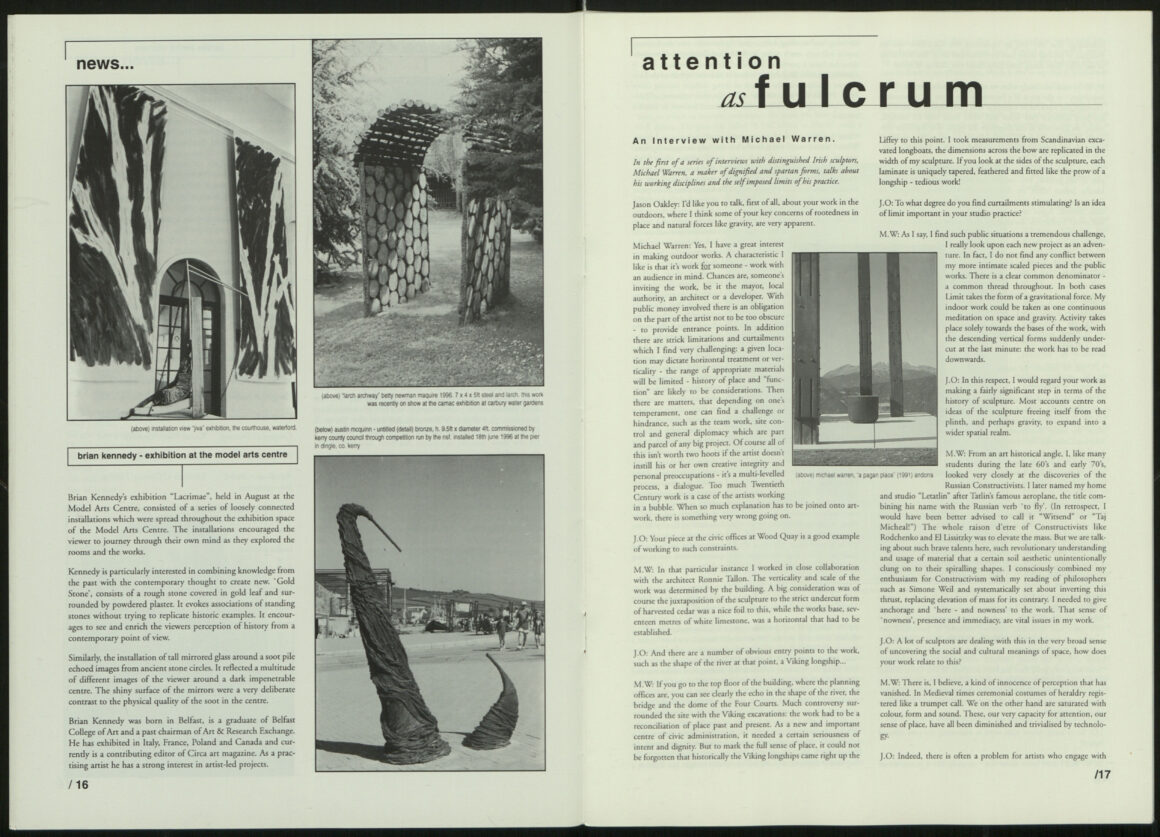

I did a work in 1994, Trade Winds and Turtles, the first non-figurative sculpture on Guadeloupe, part of the French West Indies. It’s an island that has experienced horrendous colonialisation and has suffered cultural dislocation and rupture. Also, there is meant to be racial integration, which clearly there isn’t. 6% of the population is white – the others are largely tourists. Anyway, what I did there, working with traditional boat builders – wonderful people – was to take a 5-metre diameter circle shape – a pure form, a complete wholeness – and cut and dislocate it, just as their culture had been broken, but then reassemble the pieces to articulate a new story. The re–arrangement had clear references to things maritime, which made sense to a fishing boat orientated community. The circular base, 10 metres in diameter, partly cantilevers over the quay of a small fisherman’s bay. Then, because it was made from wooden laminates, I secured the structure with pegs of tropical hardwood, which I left protruding from the form. Very interestingly, even the children responded to these pegs (this was totally unplanned on my part) as having something to do with the epoch of slavery. When you get to know these people, they talk about slavery as do say people in County Clare talk about the Famine – as if it just happened yesterday. These pegs seemingly were associated with the locking system of the human yokes slaves were made to wear.

J.O: Could you talk about the significance of your move from constructed work, with obvious bolting and bracing, to your recent Stele works, carved from single pieces of wood?

M.W: Talking of my previous timber constructions, one of the devices evident in say the IMMA work Beneath the bow (1991), that I frequently used, is an elbowing out of plane of the predominant vertical. I have always been interested in parallelism in the arts. It’s a nice thing, for example, to look at this interruption of the one-line fixation which I have explored in sculpture, in different disciplines.

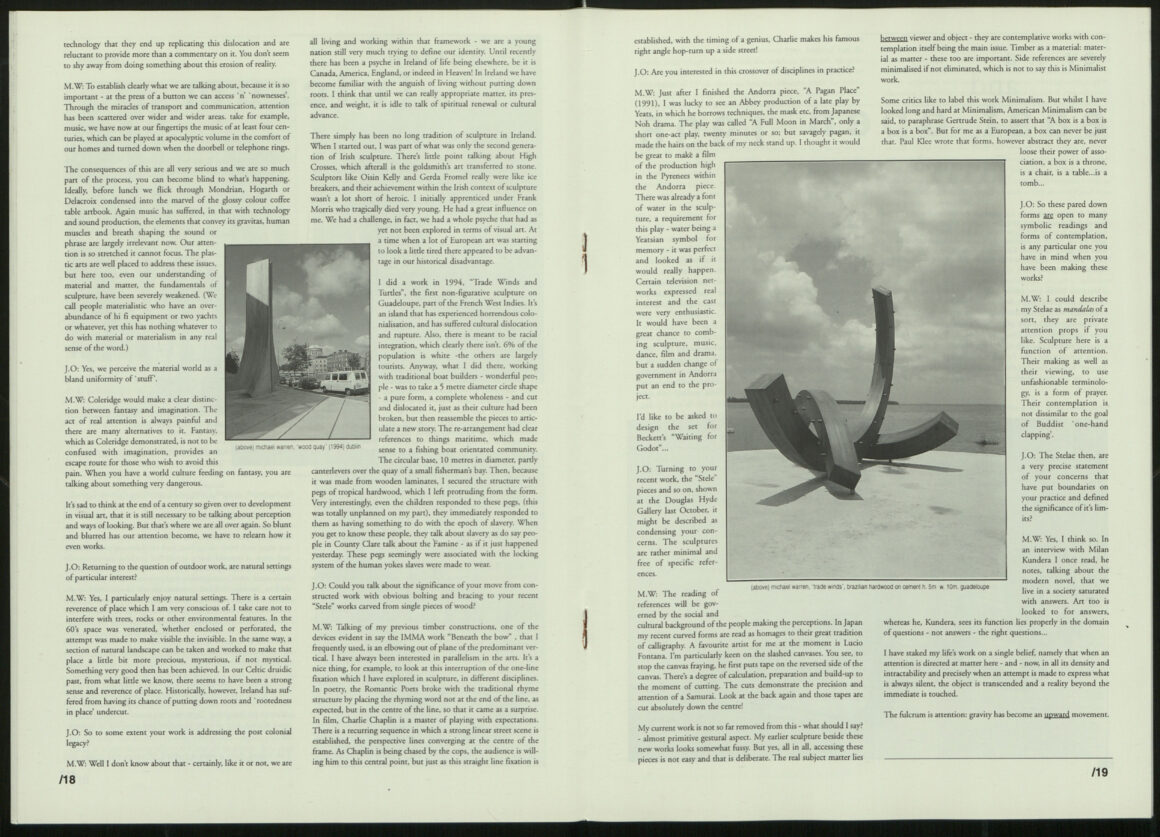

J.O: Turning to your recent work, the Stele pieces and so on, shown at the Douglas Hyde Gallery last October [‘Simple Measures’, 1995], it might be described as condensing your concerns. The sculptures are rather minimal and free of specific references.

M.W: The reading of references will be governed by the social and cultural background of the people making the perceptions. My current work is not so far removed from – what should I say? – an almost primitive gestural aspect. My earlier sculpture beside these new works looks somewhat fussy. But yes, all in all, accessing these pieces is not easy and that is deliberate. The real subject matter lies between viewer and object – they are contemplative works with contemplation itself being the main issue. Timber as a material: material as matter – these too are important. Side references are severely minimalised if not eliminated, which is not to say this is Minimalist work.

Some critics like to label this work Minimalism. But whilst I have looked long and hard at Minimalism, American Minimalism can be said, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, to assert that “A box is a box is a box is a box.” But for me as a European, a box can never be just that. Paul Klee wrote that forms, however abstract they are, never lose their power of association, a box is a throne, is a chair, is a table…is a tomb…

J.O: So, these pared down forms are open to many symbolic readings and forms of contemplation; is there any particular one you have in mind, when you have been making these works?

M.W: I could describe my Stelae as mandatas of a sort; they are private attention props if you like. Sculpture here is a function of attention. Their making as well as their viewing, to use unfashionable terminology, is a form of prayer. Their contemplation is not dissimilar to the goal of Buddhist ‘one-hand clapping’.

J.O: The Stelae then, are a very precise statement of your concerns that have put boundaries on your practice and defined the significance of its limits?

M.W: Yes, I think so. In an interview with Milan Kundera I once read, he notes, talking about the modern novel, that we live in a society saturated with answers. Art too is looked to for answers, whereas he, Kundera, sees its function lies properly in the domain of questions – not answers – the right questions… I have staked my life’s work on a single belief, namely that when an attention is directed at matter here-and-now, in all its density and intractability and precisely when an attempt is made to express what is always silent, the object is transcended and a reality beyond the immediate is touched.

The fulcrum is attention: gravity has become an upward movement.

This is a streamlined version of an interview between SSI Editor Jason Oakley (1968–2015) and sculptor Michael Warren (1950–2025), first published in the SSI Newsletter, September – October 1996, pp. 17–19. The original full text is now available on The VAN website.

visualartistsireland.com