PÁDRAIC E. MOORE CONSIDERS THE CURRENT EXHIBITION AT THE COLLEGE OF PSYCHIC STUDIES IN LONDON.

Recent years have seen a profusion of institutional exhibitions foregrounding occultism as a vital catalyst for cultural progress. A noteworthy example is the major show, ‘The Medium is the Message’, featuring over 40 artists, which continues at London’s College of Psychic Studies until 31 January. As the McLuhanesque title suggests, the emphasis here is not on any theme or subject but rather upon the methods of producing art via psychic means.

Artists featured can be divided into two groups. Deceased historical figures from the mid-twentieth century onwards, who actually engaged in forms of artmaking via channelling. Then there is the smaller group of living artists, whose work demonstrates the contemporary renaissance of interest in the esoteric. Of the contemporary artists, the work of Ireland-based artists, Samir Mahmood and Susan MacWilliam, is worthy of mention. MacWilliam’s work focus upon female luminaries from the history of mediumship, while Mahmood’s delicate, juicy watercolours resemble thought forms or tulpas – a term originating from Tibetan Buddhism relating to the visualisation of sentient beings through spiritual practice.

A notable aspect distinguishing this exhibition is the synergy between the venue and the material on display. Since 1925, this ostentatious, six-storey Kensington townhouse has been a locus for research into spiritualism and has amassed an impressive archive. Some of these holdings are on permanent display and are literally part of the furniture, such as the portraits of luminaries associated with the history of psychical research adorning the stairwells. Two years before her death, the clairvoyant painter, Ethel Le Rossignol (1873–1970) donated her visionary artworks to this organisation, and they constitute a vital foundational element of the show. Like many, Le Rossignol sought solace in spiritualism during the unprecedented trauma of World War I. In collaboration with her spirit guide (who was named J.P.F.), she cultivated a distinctive visual language that merges prismatic mandalas with whirling art nouveau motifs.

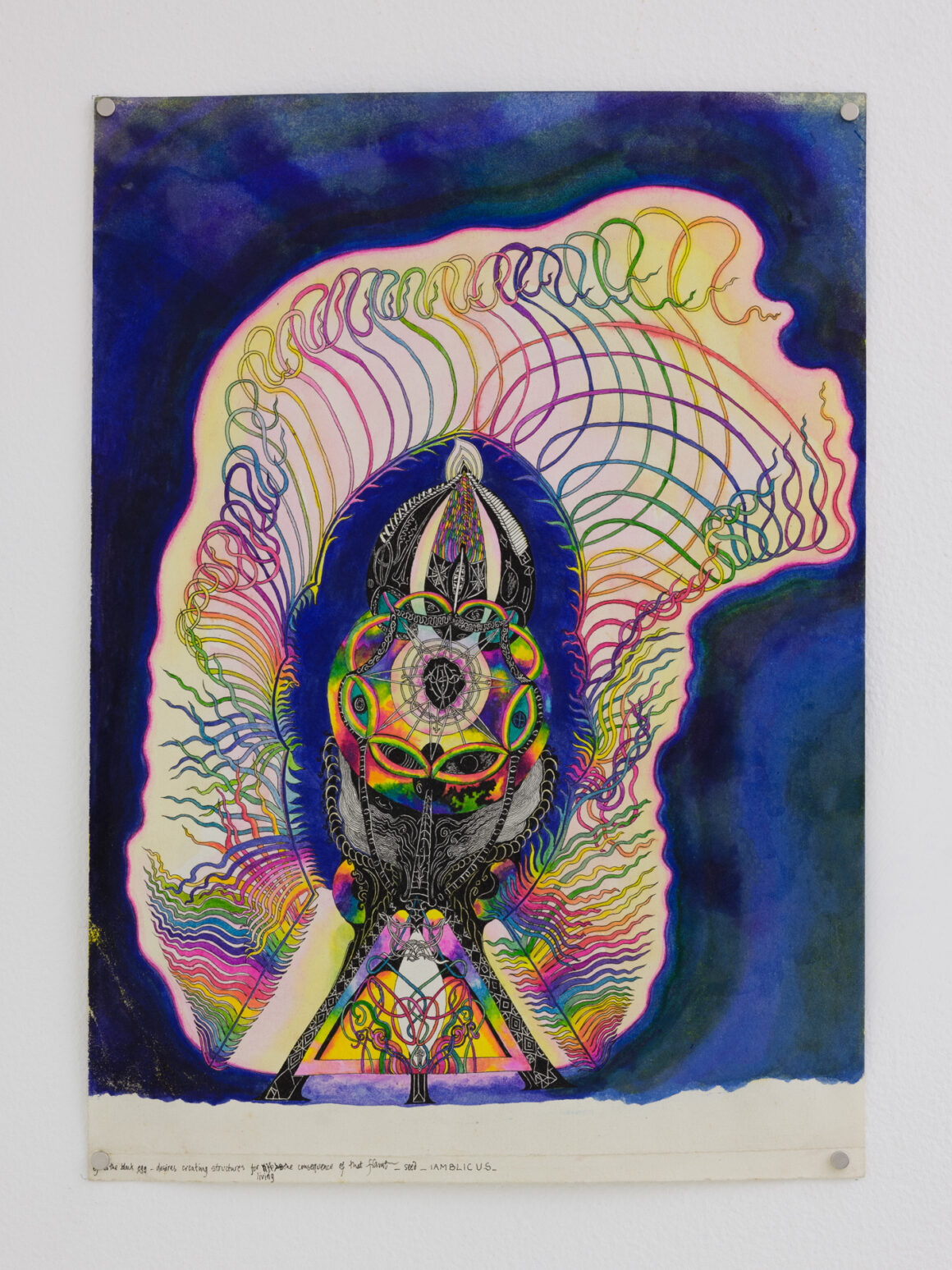

The clustering of artists into thematic categories (such as Between Worlds, The Mediums, Messages from The Unseen, and so on) lends cohesion to what would otherwise be an unwieldy multitude. Affinities and causal connections are emphasised, and art historical lineages are drawn between individuals that were previously positioned as solitary outliers. This is demonstrated by the protean Ann Churchill, whose visionary and intuitive work has recently been the focus of greatly-deserved attention. Represented here via drawings that possess a filigree quality, such as the jewel-like Iamblicus from 1975, Churchill’s works resonate with that of Le Rossignol. One of several enlightening wall texts punctuating this exhibition reveals that Churchill encountered Le Rossignol’s paintings during a visit to this organisation in the 1960s and clearly found the work of the older artist instructive.

In the 1980s, Churchill was an active participant in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) at the Women’s Peace Camp in Greenham Common, where she created textile artworks that embellished fences of the military base. This instance exemplifies how artists, invested in exploring unseen worlds and spirit realms, are frequently also committed to social and humanitarian issues. Indeed, the history of modern esotericism is replete with individuals who were active within causes such as women’s suffrage, anti-vivisection, and pacifism. This is attested to in the permanent display in the President’s Room, where, amongst the many photographs of past luminaries, is Charlotte Despard (1844–1939), the Anglo-Irish Sinn Féin activist and founding member of the Women’s Freedom League.

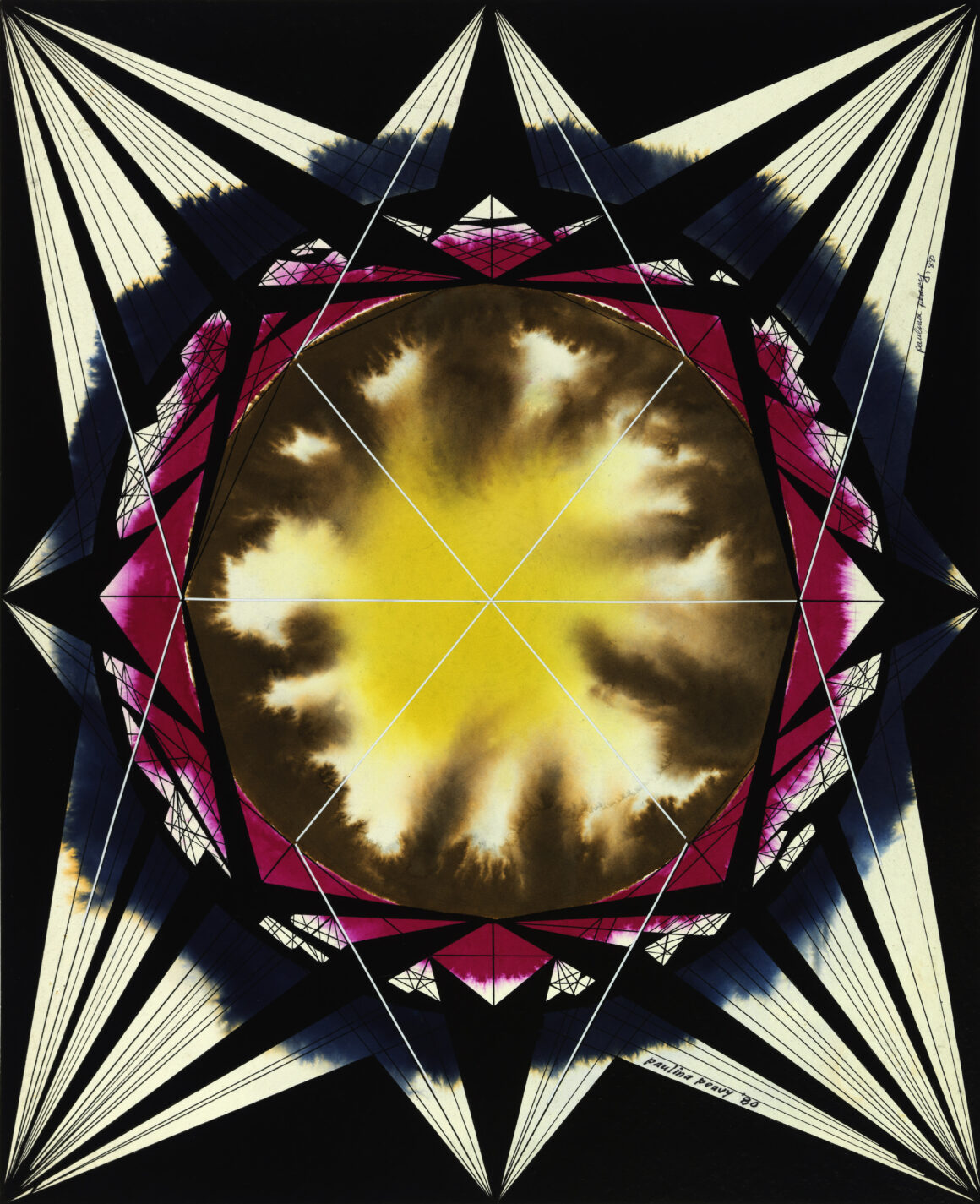

Utopian tendencies are also certainly present in the work of polymath Paulina Peavy (1901–1999), one of several artists in this show with a room devoted to their work. This is the first time Peavy’s work has been presented in the UK, and she is represented here via several works on paper and two videos, all of which were created under the direction of a nonhuman entity known as Lacamo. Peavy’s work draws heavily from New Age philosophies and is infused by the conviction that humankind was on the brink of an epoch in which feminine intelligence and ‘ovarian wisdom’ would flourish. The presented videos are visually scintillating, merging images of ancient Egyptian edifices with geometric graphics. Through these works, Peavy promulgates her conviction that we are all moving towards – and must aspire to – the state of androgyny as a means of achieving spiritual enlightenment.

Aside from the contributions of contemporary artists, most of the work in this show would once have been designated by that problematic but nevertheless useful term, ‘outsider art’, coined by Roger Cardinal in the early 1970s. Only recently has art historical scholarship become equipped to interpret such art, the makers of which were invested in practices beyond the purview of academia. This points to the importance of shows such as this one, which emphasise the seriousness of the devotional, didactic, and in some instances, even scientific intentions of these artists. And so, the most exhilarating aspect of this exhibition is the unselfconscious and assured nature of the presented work. It is gratifying to encounter artworks that have been created according to criteria that transcends any trends or art market forces and are instead the outcome of a creative union between an artist and their kindred spirit.

Pádraic E. Moore is a writer, art historian, curator, and Director of Ormston House.

padraicmoore.com