SARA GREAVU INTERVIEWS HELEN CAMMOCK ABOUT HER NEW FILM COMMISSION FOR VOID GALLERY, DERRY.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of a key civil rights march in Derry that took place on 5 October 1968, calling for the right to vote and an end to gerrymandering and discrimination in housing. This march, and its suppression by the state, is often cited as the galvanising moment of the civil rights movement, and as the starting point of the political conflict that dominated the next 30 years. In the days and weeks before the 50th anniversary, a range of events were organised by a wide spectrum of political groups and by a number of local cultural institutions. These included talks, screenings, exhibitions, rallies and two separate commemorative marches. On the anniversary itself, Helen Cammock’s exhibition, ‘The Long Note’, opened in Void Gallery, featuring a newly commissioned video work, The Long Note, centring on the role of women in the civil rights movement. This is shown alongside Cammock’s video and text-based print series, Shouting in Whispers (2017) and a reading area comprising a range of research material.

Combining interviews, archival footage, text, video, song and voiceover, The Long Note strikes a reflective tone, moving beyond a straight re-insertion of women into the historical narrative, touching lightly on issues of gendered historiography, the mechanisms of erasure, and the fallibility of collective memory. A mix of archive and new interviews (with known and less-known figures from the period) conveys both vigorous personal mythmaking and nuanced discussions of the different, often collaborative, ways that women organised – and the invisible reproductive labour of resistance and revolution. In the months leading up to the 1968 commemorations, Bernadette Devlin McAliskey – a significant representative of the civil rights era who is threaded through the layered narrative of The Long Note – commented that “… those claiming bragging rights from 1968 might reflect with greater humility on the price paid against the degree of progress made since that first march and examine their actual contribution to the reality of 2018”.1 When we look back to this lost moment of revolutionary potential, projects like The Long Note can point to some of the mistakes, oversights and invisibilities that led to the failures of the present – but perhaps they can also signpost us to their redress. I interviewed Helen on 5 October to discuss some of these ideas.

Sara Greavu: What did you bring with you into this project from previous work, in terms of methods or approach?

Helen Cammock: I guess the beginning was the conversation that I had with Mary Cremin [Director of Void Gallery]. Generally, I work on research or ideas that come from my experience or things that I’ve been affected by. So, in a way, this is not a film I would ever have made, unless somebody had approached me, because I would feel that, potentially, it wasn’t my place to do it. I couldn’t make it in the same way that I’d made other films, because I wasn’t talking about my own experience and I wasn’t talking generationally about experiences of people with whom I share a heritage. I had to take myself out of it much more than I have done in any other film I’ve ever made.

SG: Many of the women you interview are drawing on equivalencies and solidarities with the Black British experience. Was this something you were expecting to find so strongly represented?

SG: Many of the women you interview are drawing on equivalencies and solidarities with the Black British experience. Was this something you were expecting to find so strongly represented?

HC: Absolutely, yes. My dad was born in Cuba, coming from a Jamaican family. He came to the UK in the Second World War and he understood what oppression meant. He was eight when he left Cuba but the experience of coming to Britain was completely traumatic for him, so as a family, we understood those things. When we watched ‘The Troubles’ on the news in the 70s and 80s, we made the connections between the Black civil rights movement, including what was happening in South Africa, for instance. So, although I was thinking, “Oh it’s not my context,” I knew that here was a connectedness that I already felt from these early experiences. And then it was about research and meeting people; once you have dialogue, you’re into something then.

SG: I’m interested in the way you use the archive in both works, in different ways. Can you talk a bit about that?

HC: Prior to Shouting in Whispers, I think I’d only used archival footage once before. I made this film as a kind of imagined conversation with James Baldwin using an archive clip and I just felt like it made complete sense, because everything I do with scripting is all about a collage and montage of stories. So, there’s this idea that histories are never singular, they’re always multiple; but there’s always a hierarchy of how they knit together and that’s the thing that I want to interrupt, disrupt and reshape. It made sense, then, to start doing that visually, as well as in terms of the way that language works. The relationships between language, image and text are really important in everything I do.

When I made Shouting in Whispers, that was the moment I realised that, actually, I could make new stories with archival footage. So sometimes, for instance, the audio on the archival footage belongs to another piece of footage, so the stories are just moving and weaving together with each other. This works with the various registers and treatments given to different contributions. I used footage from hegemonic news sources and then I was also using the archive we managed to get from [local filmmaker] Vinny Cunningham, which has footage from people’s 16mm and 8mm cameras. Some of it is really blurry and it’s been cut together in a kind of amateur way. I think it’s really important that we get these two views: some with reporters standing there and other footage that’s kind of shonky and clumsily cut together – for me that’s beautiful.

SG: Do you feel there’s a particular ethics of working with film made by people in the community? Do you feel a responsibility to honour that material in a different way?

SG: Do you feel there’s a particular ethics of working with film made by people in the community? Do you feel a responsibility to honour that material in a different way?

HC: The ethics are always tricky and if I thought about it too much, I would come a bit unstuck. When you can talk to people face to face, there’s dialogue and it’s so much easier, because you can ask people what they’re comfortable with. You can get a sense of what might make them vulnerable or not, and then you can make decisions. There have been many occasions when I’ve really wanted to use an image or some video footage and I know I can’t. But when you make use of an archive like this, sometimes the material isn’t tagged to a name and there’s no way to contact its maker. So, I had just had to take that footage and work with it in the same way that I would with a published text. Again, if I think about that too much, it can be really problematic. I have to just check myself all the time – “What am I saying with this footage? How and why am I saying it? Who is going to be watching this and how will they read it?” It’s not a historical document or a political document, but of course, it is founded in history and in politics. I bring my own politics with me, so I knew very clearly where I was sitting, whilst making this film.

SG: I’m also interested in your use of music. I know you have used the lament as a format in previous projects and music is threaded through this work as well.

HC: The work is very layered and there are a number of different registers of text and the voice. For me, music is another way of expressing what I want to say, but I know that people receive things in different ways. For instance, I used a short extract from a Langston Hughes poem. I know that if I read that with my very English accent, it would be received in a completely different way than if I sing it. The weight of conveying language and emotion is completely different when you shift registers like that. I’m interested in the role of music in sadness but also in resistance, in work songs and political songs. I guess in many ways, laments are also political songs. In Ireland it seems the same as in the Caribbean, and in the black communities in the States: song is a used for survival, as much as it is a tool for politics, as a way of making cross-cultural, cross-racial, cross-gender connections. Music is really important in the way that I think of the world – it’s there as part of storytelling.

Helen Cammock was the winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women (2018–19) and will have a solo exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery (2019). Sara Greavu works with artists and others to make exhibitions, projects and texts. She is based in Derry. ‘The Long Note’ continues at Void Gallery, Derry until 15 December.

Notes

1 ‘PLATFORM: Bernadette McAliskey’, The Irish News, 9 February 2018. https://www.irishnews.com/news/2018/02/09/news/platform-bernadette-mcaliskey-1252271

Image Credits

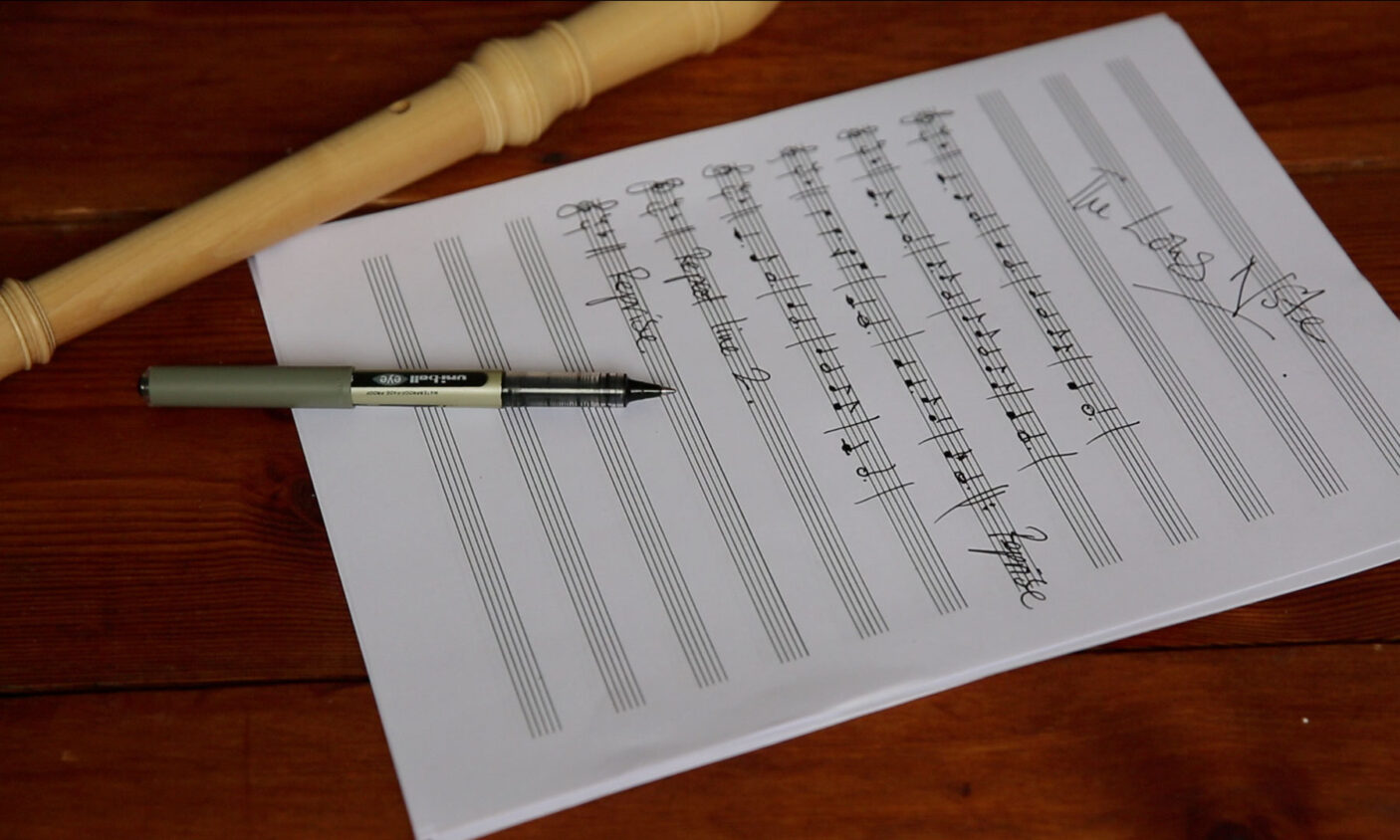

Helen Cammock, The Long Note, 2018, single channel, 103 mins, video still; all images courtesy of the artist and Void Gallery.