Last spring, many artists were restricted to their homes. As we entered into another lockdown over the winter months, our worlds again contracted to a 5 km perimeter. Almost akin to working small, we accepted how one might take advantage of the restrictions imposed on us. Some artists resigned to an inability to make work; others set up makeshift studios and laboured feverishly. Many shows were cancelled or postponed. The instability of not knowing meant that notions of DIY culture were being redefined in the digital realm.

Early morning walks have always been an intrinsic part of my practice. Familiar sights, such as ruined mills and abandoned rail tracks, form the topography of the River Boro – a tributary of the River Slaney, which rises in the dense moss overlooked by the Blackstairs Mountain. Big stately houses, such as Coolbawn House, Castleboro House and Macmine Castle, now lie ivy-clad against the riverbank. Among these once-thriving estates is Wilton Castle, reduced to ruins during the Irish Civil War in 1923 and now partially restored by a devoted farmer, Seán Windsor, over the last 17 years.

With access to cultural institutions hindered once more, Wilton Castle opened up the possibility of an exhibition venue within my 5 km border in north Wexford. The castle’s remote location seemed to chime somewhat with the solitary life of a painter (this solitude is what attracted me to the medium in the first instance). Daniel Robertson designed the castle around an existing country house, the scorched metal hanging rail still visible on the bare stone walls of the drawing room. It’s tempting to reimagine what a contemporary collection might look like today. ‘Sift’ began as a painting project in 2015, in response to the themes of memory and place. I decided to revisit the project, this time through the lens of Instagram, inviting Irish and international artists who live and work well beyond my 5 km boundary, from cities such as Los Angeles, London, Berlin and Dublin. The shared global experience of the pandemic brought to the fore a collective awareness of being in it together. Forming an artist-led group show therefore seemed logical.

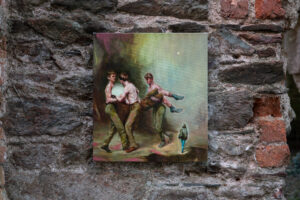

Placing work within the ruined castle became the primary focus of the project, but also filtered out in response to architectural details such as the medieval doorway, towers and underground passageway. Richard Proffitt’s installation reclaimed the burnt remains of the original central beams, reactivating small chambers within a tunnel system. Christof Mascher’s mixed media installation found space within ‘The Lady’s View’, an elevated site overlooking the central tower and river below. The architectural fabric of Wilton House was occupied by Gemma Browne, Paige Turner-Uribe and myself, including features such as windows, balconies and doors. Christopher Orr’s small-scale cryptic paintings were hosted in what would have originally been the reception, the eye of the building, seen through silver-grey Mount Leinster granite. The installation of work necessitated a discursive process, involving ongoing conversations with the artists through direct messaging and emails.

Gemma Browne’s painting, My Apron Knows Me Well, appears optimistic. Playful in scale, windows and curtains are sketchily blocked in, with a flicker of light coming through the transparent drapes. Black outlines are filled with bright colour, at times possibly referring to children’s colouring books. But not all is well – windows peer out from behind empty voids. A floating pinafore appears hemmed in; there is a sense of looking out but also looking in. A claustrophobic atmosphere swells in the air, seeming at odds with active and lively painting. Browne’s discordant themes appear candy-coated, like fairy tales gone awry.

Los Angeles-based painter, Paige Turner-Uribe, delights in quiet moments culled from a variety of sources, such as cult films, found images and personal ephemera. John D. Hancock’s horror film, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death1, has been a repeated source of inspiration for the artist, often compared to Irish novelist Sheridan Le Fanu’s Gothic novella, Carmilla2, in which themes of unreality play out in an inconclusive manner. A sweet, sun-drenched melancholy frames otherwise banal daily encounters, such as waking from sleep, sitting at a park bench, or pacing along a sidewalk. Turner-Uribe dresses her paintings in titles that lend a strange register. Fuzzy chartreuse narratives sometimes dip into cool blues and mauves.

‘Cut and paste’ is a practice associated with early Dadaists like Hannah Höch, who appropriated imagery from magazines, particularly human forms. Confronted by scale, her photomontages undoubtedly informed punk zine culture of the 1970s. Where the Long Shadows Fall, a painting by Christopher Orr, sees three young men carry what appears to be a wounded colleague. There is a striking likeness in their faces, their upper torsos bare. Olive military uniforms are smeared in magenta, which is echoed in the foreground and sky directly above. Their shorts are indicative of a more tropical climate. A puzzling orb-like face emits light, a moon or sun above signalling events below. Perhaps Orr’s more stark reference to photomontage is a diminutive figure, dressed in jeans and hoodie, a handbag slung over her shoulder. A possible nod to Rococo, she too releases traces of light.

Christof Mascher often presents us with art historical vignettes. At times brooding, there are many passages through which one can enter his paintings. Nocturnal houses emerge from fog; eccentric architectural forms give way to a pre-industrial way of life; tight-knit communities huddle to shelter from the cold; the framed glow of light from oil lanterns projects random patterns. Mascher’s palette of mucky browns is all his own. There is something musical about these arrangements, with swatches of violet meeting in polyphonic unison. Dancing horses can mingle with dinosaurs – minute detail, calling to mind the Dutch Renaissance painter, Hieronymus Bosch.

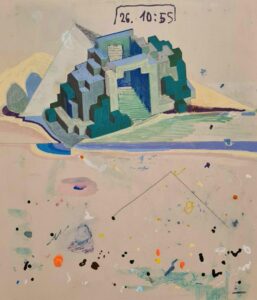

Civic aspects of the built environment have long occupied bodily interests within my own painting practice. Uprooted from distant sources, relics such as disused canals and aqueducts sit alongside shop fronts, housing developments and alleyways. In Houses That Are Gone…, masked or shrouded figures drift through, while a barely-there figure gestures beneath a thicket of leaves. A garland cuts across and terraced houses are temporarily suspended. Perceptual barriers render themselves as pockets of dense social activity. A slight sparring process occurs, recently taking place on fluorescent grounds.

Richard Proffitt’s practice is a hyperactive hoarding of debris, stashing a mind-bending assortment of objects – from charred driftwood and paint-stripped bottle caps, to cassette tapes and seaweed. These scattered remains have a ‘happened upon’ feel about them. Riffing on aspects of hippie counterculture, his paintings are conceived with a random logic; dream catchers sit alongside images of birthday cakes, tree houses or temple sculptures. Leading titles point to mystical themes, such as pagan rituals and sun worship. In an archaeological fever, he assembles work that seems to suggest half-imagined human activity.

Given the unpredictable nature of lockdown, waiting for cultural institutions to reopen has at times been frustrating. As a result, DIY culture has never been more alive. Different forms of presenting painting practice have emerged online in recent times; however, nothing entirely replaces the physical act of meeting a painting first-hand. But for now, it’s taking a detour to places that might have seemed unimaginable in pre-pandemic times. Installed as a winter show, the project unfolded over several weeks via Instagram (@siftpainting #siftpainting). How work was framed within the space was important, taking in architectural details and individual responses to particular parts of the building. This meant that there was a gradual feeding of each respective practice.

John Busher is an artist and occasional curator based in Wexford.