Solstice Art Centre, Navan

12 January – 1 March 2019

The exposé of Cambridge Analytica last year showed us how we are complicit in our own surveillance. It’s no longer just footage from omniscient CCTV that tracks us; self-authored social media data is also capable of being harvested, hacked or stolen. And thanks to unscrupulous but canny work of electioneers, the world now has Trump and Brexit to deal with. As the wordplay in the title suggests, the current exhibition at Solstice surveys surveillance-related art from multiple perspectives.

The show originates from Centre Culturel Irlandais Paris – Ireland’s cultural outpost in Europe – and is curated by centre director and Belfast native Nora Hickey M’Sichili, who began the project at her family home, on discovering it was used as an ‘intelligence centre’ during WWII. It is The Troubles however, that provides the historical backbone to this show.

Two large photographs by Willie Doherty from 1985 observe Derry with dry, ominous words as overlaid text, describing yet subverting the banal urban landscape. 20 years later, Donovan Wylie photographed the dismantling of army watch towers on the border, documenting landscapes once littered with the infrastructure of looking and listening. These stark images introduce the object but not the subject of surveillance – something which proves more elusive than should be expected across the entire show.

The banality of surveillance is evident in Colin Martin’s large photorealist painting of a canteen area at Facebook’s Dublin offices. Based on a snapshot taken on an open day, Martin’s intense detailing misdirects, as it discloses no secrets or dark revelations regarding the company’s guarded internal operations. The futility of revenge against our technological overlords is more apparent with Martin’s accompanying small painting of a child’s head, wired with EEG electrodes.

This belied banality is a common thread. John Gerrard’s 24-hour simulation of a Google data farm may show some random industrial buildings, but they are made sinister by imagining what is inside. Roseanne Lynch’s photograph of an actual Google data farm off the M50 in Dublin may be static and analogue, but it is just as portentous. Conversely, Karl Burke’s Martian-like landscapes are digitally fabricated from computer virus code that was originally used, amongst other things, to disrupt Iranian enrichment centrifuges in 2010. The ones and zeros have been repurposed to map a virtual geography. Oddly, the prevention of nuclear annihilation has created barren post-apocalyptic landscapes; sublime contradictions abound in these human-free works.

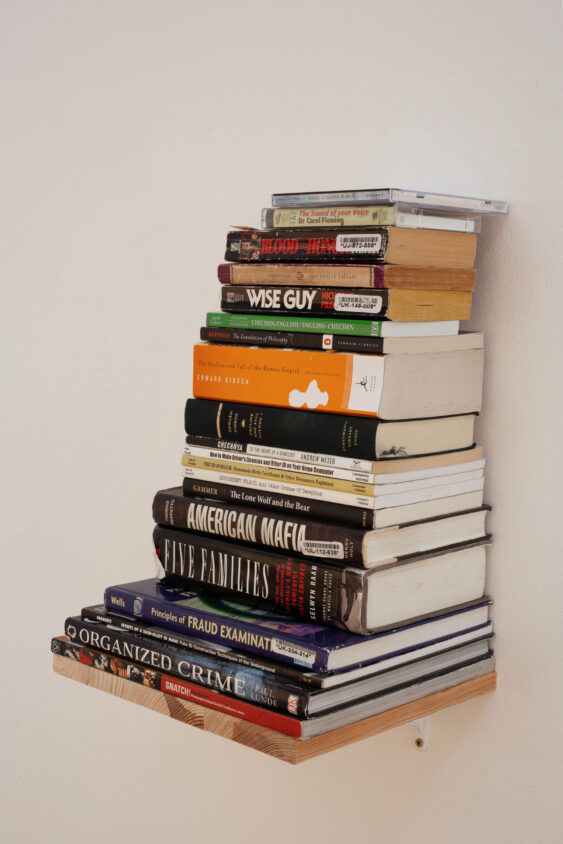

Alan Butler’s pizza-covered drone forms part of a mock-advertisement-cum-expo stand, promoting cryptography for children. It’s a mega-mix, where pop eats itself with extra pepperoni, flanked by an Amazon Books wish-list of a bomber from Boston. Digital traces are mocked here but are then manipulated back into a critical assemblage. The adjacent woven carpet by Jim Ricks reappropriates the Afghanistan tradition, begun during the Russian occupation, which incorporated military vehicles in carpet designs – upgraded now to deadly decorative drones.

With the human subject largely absent from the exhibition, Teresa Dillon’s cardboard CCTV cameras focus on a UV anti-bird gel as another incursion into urban life. But there are figures in Ian Wieczorek’s paintings and in Benjamin Gaulon’s hacked and not-so-closed CCTV footage, which shows how unaware we are of the open wireless networks watching us and how they can so easily be harnessed. Declan Clarke also provides some humans to surveil, in his 35-minute classic spy film drama. Here the gaze is gendered male, with the artist stalking a female researcher through galleries and streets.

As a corollary, the female gaze fights back through artificial intelligence in Caroline Campbell’s research piece, in which an AI programme is taught to see the ‘wrong’ stuff – in this case, to ignore the faces of activists in the footage of protests at Shannon Airport. This resistance is complimented in Nina McGowan’s adjacent sculptural assemblage, which offers a conceptual route away from surveillance. A large ornamental pinecone stands in for a pineal gland, illuminated by an array of large surgical theatre lights. The pineal is being interrogated as the site of the soul, now a giant mechanical flower in bloom, as a spiritual form of resistance to the presence of all-pervading surveillance.

Alan Phelan is an artist based in Dublin.

Feature Image:

Alan Butler, Surprise Party Breath, 2015, Contents of Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s Amazon.com Wish-list, installation view, ‘Surveillé·e·s’, Solstice Arts Centre; photograph by Paul Gaffney, courtesy Solstice Arts Centre.