JOANNE LAWS SPEAKS TO THE SOME OF THE ARTISTS DEVELOPING NEW WORK FOR THE 39TH EVA INTERNATIONAL PLATFORM COMMISSIONS.

Joanne Laws: What was the rationale behind your original project proposal, particularly with reference to the ‘Golden Vein’ thematic, outlined in the commission brief?

Áine McBride: My motivation to respond to the thematic was the potential it offered for an abstracted response. The strip of land of the Golden Vein approaches an ideal(ised) state, offering a framework for conceptual projections around broader notions of land and landscape, place and site. The perceived perfection of this area allows it to be considered in a way akin to a fictional space. How could this space of thought be manifested physically?

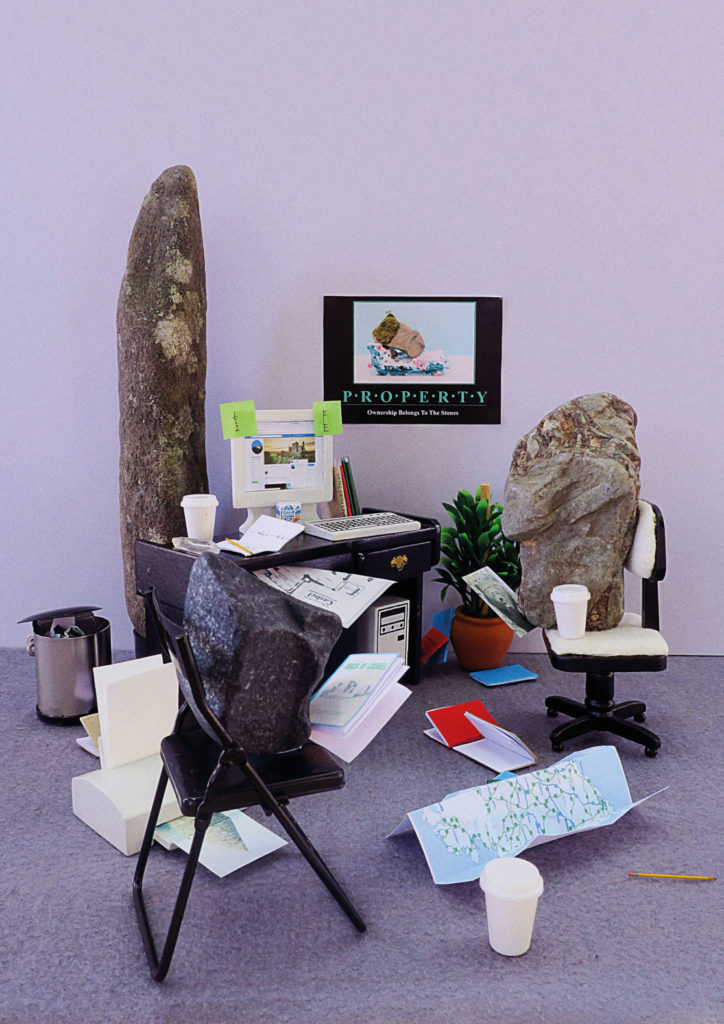

Laura Fitzgerald: My project will explore ideas relating to land use, inheritance, capital and survival, amongst members of the farming community in the Golden Vein area. I will be conducting interviews with farmers and using stones collected from the area, in order to discuss these issues. These themes will be further explored by antropomorphising the rocks I’ve collected and situating them within a variety of domestic, office and studio scenarios. I have long wanted to compare administrative aspects of the art world (such as funding applications) to those of the farming community, and the mentality that accompanies this quest for survival, both in practical terms but also in physiological terms, reimagining this as the stones’ ‘personal weather’.

Emily McFarland: At the start of 2018 I began collecting material documenting a series of actions taken by members of a small rural community living in the Sperrin Mountains of West Tyrone, close to where I grew up, in response to plans submitted by a Canadian mining and prospecting company, called Dalradian Gold Ltd, to the Department for Infrastructure in 2017. Particular conversations taking place within the community at that time and research I was doing overlapped with the starting point for the 39th EVA International – thinking through ideas of land and its contested values within the context of Ireland today.

Eimear Walshe: The Golden Vein, as a historic term used to describe a fertile area of land in Munster, kind of romanticises the yield and value of the land in agricultural terms. Of course, it is a very urgent time to rethink (and materially alter) how land is valuated, shared, distributed and inherited, and Irish history provides us with a lot of illuminating precedents for this. Colonialism, migration, famine, economic vacillation and cultural trauma all play their part in where we find ourselves today. However, I’m specifically interested in how the libidinal economy impacts our relationship with land and housing; how our desire for intimacy, privacy and sexuality informs (and possibly restricts) our vision for how to live together.

JL: Can you discuss some of your ongoing research inquiries and methods?

ÁMcB: My ongoing considerations are relatively broad and concern ideas of architecture, our relationship to space and place, and how these concerns may be communicated. Identifying a suitable site for the artwork is also ongoing. This search is being done in tandem with the gathering of visual research. I’ve began collecting a set of digital and analogue images from direct and indirect observation, which are serving to drive the work in a formal capacity and may be a potential form of output in themselves.

LF: I just bought a Ladybird ‘Learning to Read’ book called The Farm, which I’m planning on weaving into my new film. I also recently attended the Teagasc National Dairy Conference on 3 December 2019, to gain insights into the contemporary concerns of farmers working in the industry. I completed a project in September 2019 for Cashel Arts Festival, called ‘Rock Stars’ (curated by Emma-Lucy O’Brien), which has played a pivotal role in consolidating my thinking about the tone of the project. I made two postcard images, called Meeting of Rock Uprising I and II, that depict scenes of a group of rocks discussing how they could ‘take back’ ownership of the Rock of Cashel in County Tipperary – the seat of the Golden Vein. So, the premise of the project is very much within the ‘hands’ of the rocks, imagining things from their perspective and trying to understand how they would reorganise the use of land in the contemporary age. Preliminary research and production methods will build the actual content of the film itself, which for me is embedded within procrastination and the fear of making new work – in particular, new video work. Some of the self-reflexivity referenced in the film will include a fear of failure – channeling the disappointment of farmers, of the stones, and of the curator, Matt Packer – and using an overarching theme of ‘imposter syndrome’.

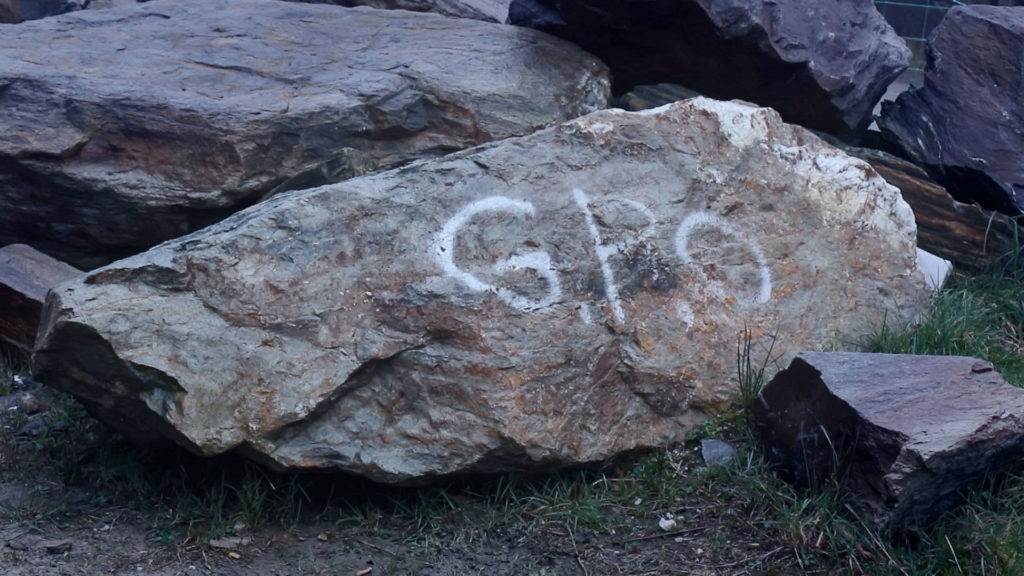

EM: As part of my ongoing research, I have been looking at ways in which shared collective memories, cultural narratives and material histories are produced and what gets preserved or lost at a specific historical conjuncture. Bearing witness to the ecology of a particular landscape, preserving embodied memory by recording it, forming a contingency archive of a place in time, is something I’ve been thinking about as a method for resistance and transformation. I have been collecting moments of testimony from rural activists currently occupying land acquired by the mining company, forming the Greencastle People’s Office – a collection of caravans high in the mountains overlooking a valley of farmland, and utilising documentary forms to note particular details in the topography, non-human life, voice and song from the camp and surrounding mountains of West Tyrone. The dialogue shifts between shared experiences and personal accounts, converging with wider notions of solidarity, sovereignty, circulation of capital, ideologies of capitalism and particular legacies of historical colonialism, intersecting the global and the local.

EW: I’ve been learning about the history of the Irish Land Wars and the life of Land League co-founder, Michael Davitt. I believe the Land Wars are an under-discussed aspect of Irish history that feels very pertinent today. I’ve also been filming in sites related to these histories and sites along my own trajectories of movement across the country. To try and gain better emotional understanding of the subject, I’ve been learning to sing traditional and country songs that deal specifically with romance, sexuality, class mobility and housing. Another aspect of the research has been in the gaining of knowledge about the social, political and affective consequences of having sex in different sites in Ireland: public, private, rural, urban, humble, monumental.

JL: How do you envisage the public manifestation(s) of this work, in the context of EVA 2020?

ÁMcB: The work is conceived of as an outdoor work. The material and form of the work will be suited to, and informed by, the site. I think there is an option here to engage with the prospect of change. Could the work be manipulated to weather/develop/have a non-static form that could evolve over the course of the biennial’s two-month run? The work’s manifestation is likely to focus on creating a landscape onto which other works might be sited. A constructed ground might gather on its surface, in reference to construction foundations. How might the creation of a surface draw together various strands of past, present and future? And ultimately how can elements of these be juxtaposed to produce or provide space for poetic thought?

LF: I am hoping that the video will be shown on an analog television set that people used to have in their homes – now more or less defunct, having been widely replaced by HD flat screen TVs. It might take the form of a series of separate videos relating to each season – so four videos in total. These pieces may end up chaptered on one TV or screened on four separate TVs. I’d like to install the work in the kinds of places where members of the farming community might make pilgrimage to when visiting the city. Potential sites could include the main branch of a bank, the dairy aisle of a supermarket, a hardware store, or even a ‘Cafe Kylemore’-style restaurant within Limerick City – any of these places might be appropriate.

EM: Right now, I am in the process of producing a sequence of short films and a longer single-channel video, which I see as fragments in a series. The films will be shown alongside ephemera and artefacts from informal archives compiled by individual community members since the beginning of their actions and establishment of Greencastle People’s Office.

EW: I’m making videos and drawings at the minute. I’m also writing about the affective relationship between modes of housing and sexuality from a more personal perspective, which I’ll publish in some capacity. I’m especially excited about EVA’s immersive and adaptive approach to sites within this iteration of the biennale, especially considering how the location and thematic are so intertwined. I’m hoping I can respond appropriately to that context in the installation of the work.

The 39th EVA International will run from 4 September to 15 November, across venues in Limerick city and beyond.

Feature Image: Eimear Walshe, video still (research image), 2019; courtesy of the artist.