Millennium Court Arts Centre, Portadown

2 November 2018 – 23 January 2019

The current exhibition, ‘MANMADE’, at Millennium Court Arts Centre, features the work of several artists examining marine debris, coral life and metaphors of irrevocable danger carried by the sea, based on increasing levels of human pollution that threaten the oceanic ecosystem. The centre has developed an accompanying public programme, comprising a range of outreach activities, aimed at promoting environmental consciousness. This agenda acts to both serve and subvert the curatorial theme: collectively the artworks explore this subject and its associated materials, yet the conceptual integrity of the exhibition is undermined, in its framing as some sort of awareness campaign.

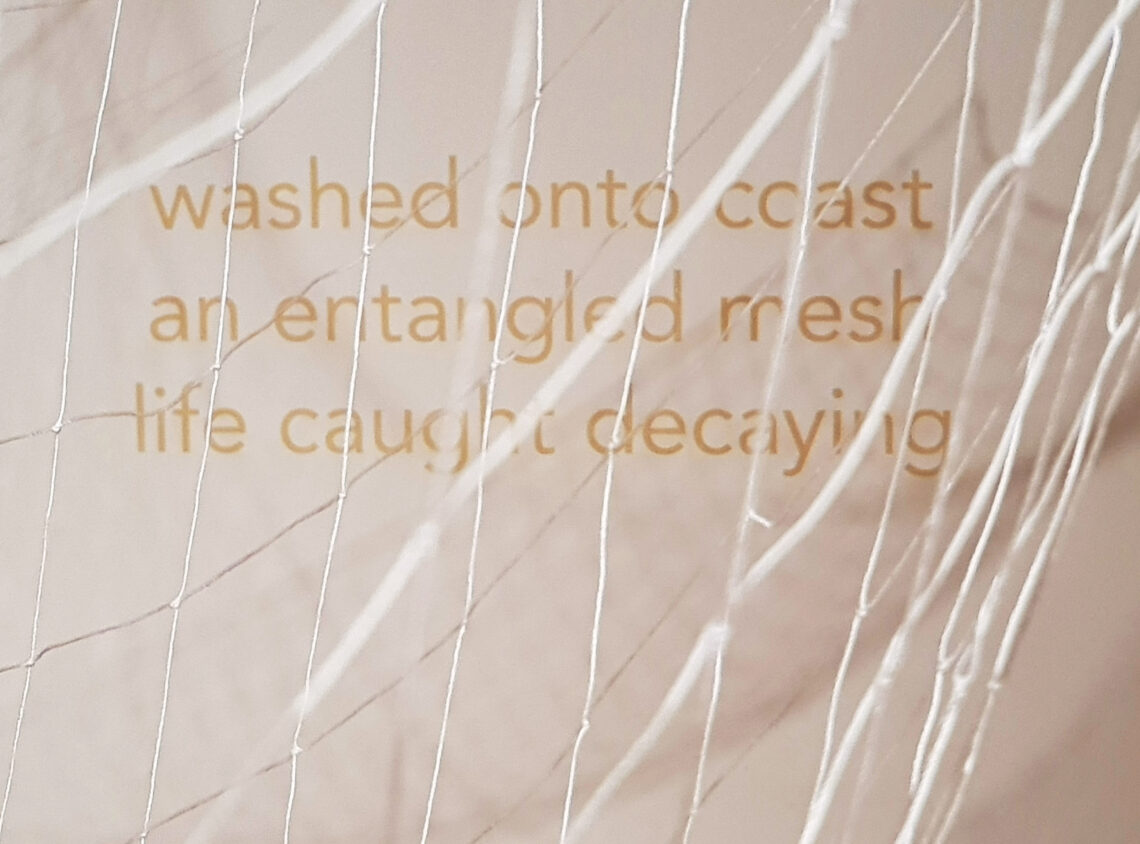

One element that weaves throughout the works on show, is the repeated use of text in various forms, each uniquely interpreting the multiple elements embedded within the curatorial inquiry. In Ghost Net (2016) – a collaborative work, by Kathryn Nelson, Julie McGowan and Sandra Turley – a large white cotton fishing net is rendered almost invisible. The net’s presence is betrayed by the webs of overlapping shadows it casts onto the surrounding walls, intertwining with the soft yellow lettering of the accompanying wall text. These short verses highlight both the sinister function of the apparatus and its delicate qualities, alluding to human intervention in the environment, including the ancient tradition of fishing, which is being quietly scrutinised. These short and momentary poetics reflect this antagonism; emerging broken and lost, the words are reassembled, ultimately changing their agency.

This shift in agency corresponds on a fundamental level with the reclaimed materials that feature widely in the exhibition – once considered pollution, now categorised, arranged and reconstituted as artworks, and given autonomy in the gallery context. Recent Ulster University graduate, Kate Ritchie, presented a series of sculptural installations titled Beachkeeping No.1, No.2 and No.3. The artist’s regular beach combings were presented as a cabinet of curiosities – taking the form of a traditional kitchen dresser – as well as stacked Perspex boxes on the gallery floor. Categorised by colour, shape or form, the variety of collectibles included animal bone, multicoloured rope floats, petrified sea sponges, workman’s rubber gloves and manufactured objects of all shapes and sizes, reflecting Ritchie’s durational commitment to this work. Some objects have been eroded beyond repair, to resemble the abstract sculptural forms of Tony Cragg. Unfortunately, Uniform of Debris (2018), a video and sound installation by Kathryn and Roy Nelson, was experiencing technical difficulties during my visit, and therefore cannot be discussed in this review.

Shambles on a bodyboard (2018) is another text-based work, developed by Mitch Conlon in collaboration with Belfast based tradesman Bobby Seggie. The slogan, “She/He/They Deserve to Hear the Wetlands Play”, refers to a time when Conlon’s socially-engaged practice came into contact with activism and protest. The projection distils a potential mantra of social change, carving out a slightly more localised political position amongst the rubble. Seggie employs the traditional methods of handmade signwriting, with the large white typeface amplified by the saturated colour image of rippling water, creating a pared back and mystifying aesthetic. Apparently, the work is incomplete, however this presentation in the arts centre functions as an initial design plan – a work in motion ebbing at the shoreline – that resonates with the accumulative threads of neighbouring artworks.

The projection work sits in stark opposition to another piece of text – a large black vinyl statistic on the adjacent wall, proclaiming that the amount of plastic dumped every minute into the ocean equates to that of a truck-load. The inclusion of this statement is problematic. Situated beside a series of interpretive artworks, it has a flattening effect, framing them as some sort of ‘awareness campaign’, with a ‘child friendly’, educational doctrine. The publication reinforces this line of inquiry, claiming that the exhibition “explores the devastating long-term effects plastic is having on our precious oceans”, thus positing linear and prescriptive interpretations for the work on show, while masking other potential narratives that remain unrealised. This shiny black declaration provoked my scepticism, because it is not an artwork by one of the artists involved. It strikes me that conflicts between curatorial intention and public relations have become increasingly common within public institutions, which runs the risk of diluting the nuanced intentions behind certain artworks, in order for them to appear more topical or ‘accessible’. This can also result in artistic validity being outweighed by thematic generalisations, as a bridge to tentatively connect artistic practice with the mainstream public.

Tara McGinn is an artist and writer currently based in Belfast and an MFA candidate at the University of Ulster.

Image Credits

Kathryn Nelson, Julie McGowan & Sandra Turley, Ghost Net, 2016, cotton and text; image courtesy of Millennium Court Arts Centre.

Kate Ritchie, Beachkeeping No.3, 2018, found mixed plastics, bone, wood and cabinet; image courtesy of Millennium Court Arts Centre