JOANNE LAWS SPEAKS TO JOHN HUTCHINSON ABOUT HIS 25-YEAR DIRECTORSHIP OF THE DOUGLAS HYDE GALLERY.

Joanne Laws: Your vast contribution to the Irish visual arts is fondly conveyed in a series of thoughts, reflections and tributes by artists, colleagues and friends. How do you feel about these comments?

John Hutchinson: I found it a very strange experience. It felt a bit like reading my own obituary. But by and large they were lovely and very generous. Michael [Hill] and Rachel[McIntyre] put them together with a lot of work and I’m very touched and grateful for all their efforts.

JL: Among these comments, Alice Maher described her 1994 solo exhibition, ‘Familiar’, as pivotal, not only in launching her career, but in starting to see herself as a “full-time practicing artist – no going back”. How important is it for you to champion emerging artists?

JH: The funny thing was that at the time I wasn’t long there either. I was learning my trade while Alice was learning hers. She said that I gave her another six months to develop extra work and I only vaguely recollect this – I’m sure it was just an instinctive or natural response. However, I rarely champion anyone. Besides, I always made an effort to have a balance between emerging and established, Irish, non-Irish, women, men, minorities and so on – a basic structure to avoid opening myself up to criticism for having too much of this or too little of that.

The other thing I had to bear in mind was a spread of different mediums. Nonetheless, if you look back, you’ll find a sustained interest in painting and photography. There was an emphasis on installation in the early 1990s, when it was very fashionable, but as other galleries began doing more installation or conceptual work, I backed away from it. I tried to work with a sense of necessity, of need, with something I wanted to see happen. I increasingly gambled on the belief that if I found it interesting there would be other people out there who would too.

JL: In your curatorial approach, the philosophy of dualism seems to allow binary opposites to coexist, emphasising the thresholds between the expansive and the intimate, familiar or strange, even the venerated art object and the discarded artefact or relic. Can you say something about dualism?

JH: Actually dualism in itself interests me not at all. I’m much more interested in – to use a metaphysical term – ‘oneness’. The question is, how does one experience, explore, manifest or share that sense of oneness? There are a number of ways to do this. For example – and of course I’m simplifying – in Hegelian dialectic you put opposites together and the result is something which combines the two. That’s one way, and this is the way of contrast that you describe. Another is the idea that you begin with oneness and end with it. If you do that, relationships are established like networks, in a kind of unfoldment, which is less a set of binary oppositions of contrast than an investigation or exploration of connections – between big and small, outside and inside, absence and presence. It’s this richness of interrelationships that interests me.

JL: Your curatorial approach seems rooted in questions of identity and spirituality. Perhaps you could discuss some of your influences?

JH: When I first started at the gallery in 1991, I wrote a short piece for Circa in which I said that the programme would be based on themes of identity and absence. These ideas served a purpose initially, but my approach gradually became more intuitive than rational. The pragmatics of curating are pretty straightforward; the rest is down to the depth and breadth of your experience, the people you hang out with, the books you read, the music you listen to and so on. The question of what a curator is and does is a thorny one, particularly as there are so many approaches one can follow. It’s a bit like writing: almost anyone can write a book, but the question is, can you write an interesting one?

JL: With a shake-up of directors and curators happening across many Irish arts organisations at the moment, we are confronted with the (often anxious) realisation that, to varying degrees, the curator is actually the institution. Do you have any thoughts on this?

JH: Sometimes, when radical shifts happen, the contrast with what went before is very evident. I wouldn’t be surprised to see dramatic changes at the Douglas Hyde, and many people may well prefer them. Others might miss my approach – but that’s life. In general the art system is very antipathetic to people staying a long time in one place. Curatorial careers are increasingly globalised and ruthless – a curator will often come into an institution already thinking about moving on to another job within a year or two.

I worked for 25 years in the Douglas Hyde Gallery, where I probably put on around 250 exhibitions. One of the best-attended shows I was involved in was the Kalachakra Sand Mandala with the Tibetan monks. We had phenomenal numbers for that. On the final day, we collected donations for the monastery and they came in so fast that the money boxes were overflowing. That all happened through word of mouth. If an exhibition touches people and they’re interested, then that’s fantastic, but it often won’t happen. That seems OK to me.

JL: Have you programmed a few things at the Douglas Hyde for 2017?

JL: Have you programmed a few things at the Douglas Hyde for 2017?

JH: I have bequeathed three solo exhibitions: Sean Lynch (17 February – 5 April) and Isobel Nolan (June – August), that I felt were appropriate to the gallery and with which any incoming director would feel comfortable. The current exhibition by Dennis Dineen (21 April 21 – 27 May) is a bit of a wild card. Dineen was an amateur photographer who ran a pub outside Cork. He took photographs of locals in the back room for passports, first communions and other events throughout the 1950s and 60s. Now, not every curator will like these photographs, because they’re odd things, but I think they are wonderful. I didn’t want to programme shows that I wouldn’t do myself, but by the same token I didn’t want to leave shows that were too obviously ‘me’. Perhaps the Dineen show is the exception.

JL: Under your directorship, the Douglas Hyde also became renowned for its commitment to publishing. When and how did this practice unfold?

JH: There were three stages. I inherited a budget of £17,000 for a simple A4 catalogue when I started at the gallery in 1991. Massive amounts of money were spent on catalogues in those days. I started off working with a couple of designers and eventually with Peter Maybury, with whom I had a very interesting and productive relationship. At this time, every catalogue was designed according to individual needs, budgets and aesthetic requirements. The second stage was to find a format that could be applied to all artists, that was affordable, democratic and could provide an identity for the gallery. I came up with the idea of small, bound A5 volumes and we began to print abroad. The artist was given the outside format and told they could do more or less whatever they wanted within it. It worked like a dream. That lasted up until the economic crash, and then we couldn’t even afford those, so I came up with a different format, printing digitally and designing in-house. Generally, I wrote the texts for the small books, and they were incredibly efficient financially. We were able to sell them for €5. In the last few years we were typically printing 250 or 300 copies; often they would sell out and we would make a modest profit.

Joanne: Do you feel that printed matter does more than its digital counterpart?

JH: Oh yes, much more. It looks and feels different when you have an object in your hand. One of the ideas behind the scale of the small publications was that they were meant to be, subconsciously, a bit like a little prayer book – something intimate that you could stick in your pocket. There was something slightly precious about them, but on the other hand if someone spent €5 and didn’t like it, they could toss it away. I like those ambiguities and contradictions. But that normally only comes across with a physical object.

JL: In foreword of the 2009 publication Questions of Travel, you reflect on art as being founded on “stillness and familiarity”. To what extent does art feature in your future plans? Will you still go to openings? Are you someone that likes to travel? What will you miss?

JH: No, I disliked openings, even when I had to host them. I don’t want to set foot in the gallery again for a while, so the new director has time and space to settle down and I can develop a new persona. But I do enjoy keeping in touch with artists, colleagues and friends. It’s interesting to see, though, how transient your influence is. You’re left with the people you want to see and who want to see you.

In some respects, it’s taking longer to settle than I thought. What I will miss are the dialogues with artists and hanging shows. They are things I wouldn’t like to do without, but how they can be sustained I don’t know. I won’t miss the increasing bureaucracy or the politics of the art world, but I will miss standing with an artist in the Douglas Hyde’s big concrete room, or even in the little one, and thinking “right, okay, where do we put this?” I loved that. I travel mentally; I don’t travel physically much anymore. I’m a big reader. My house is full of stuff. I collect things. I’ll probably have to stop now that I’ll have less money, but I accumulate books, CDs, films and objects from all over the world. They feed me. I garden, I walk, I listen to music, and I stare at the sky – and that does me, you see.

John Hutchinson was director of the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, from 1991 to 2016.

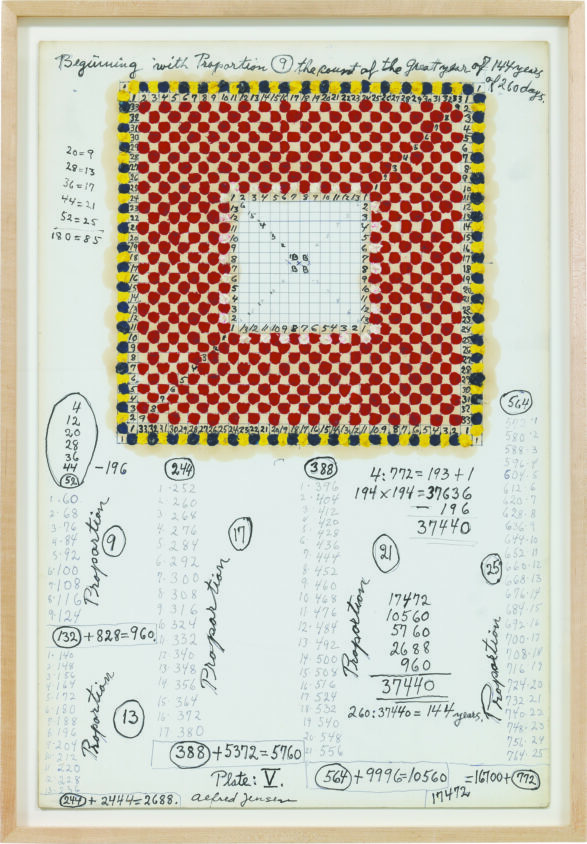

Images: Alfred Jensen, installation view, the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Gallery 1, March 2010; ‘Turkmen and Uzbek Children’s Clothes’, the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Gallery 2, May 2016.