Atom Gallery, London

5 – 26 May 2018

There is an immediate urgency to ideas surrounding the digital – whether in terms of its technological capabilities, the dark underbelly of its culture, or in its increasing influence across political and economic spheres. It feels definitive of the present moment in a way that is all-consuming, whilst also being difficult to fully articulate. Belfast-based street artist and printmaker Leo Boyd wrestles with the philosophical questions posed by artificial intelligence, by taking influence from the work of Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom. Are we living in a computer simulation? Perhaps life as we know it is nothing but fragments of data on some other being’s hard drive…

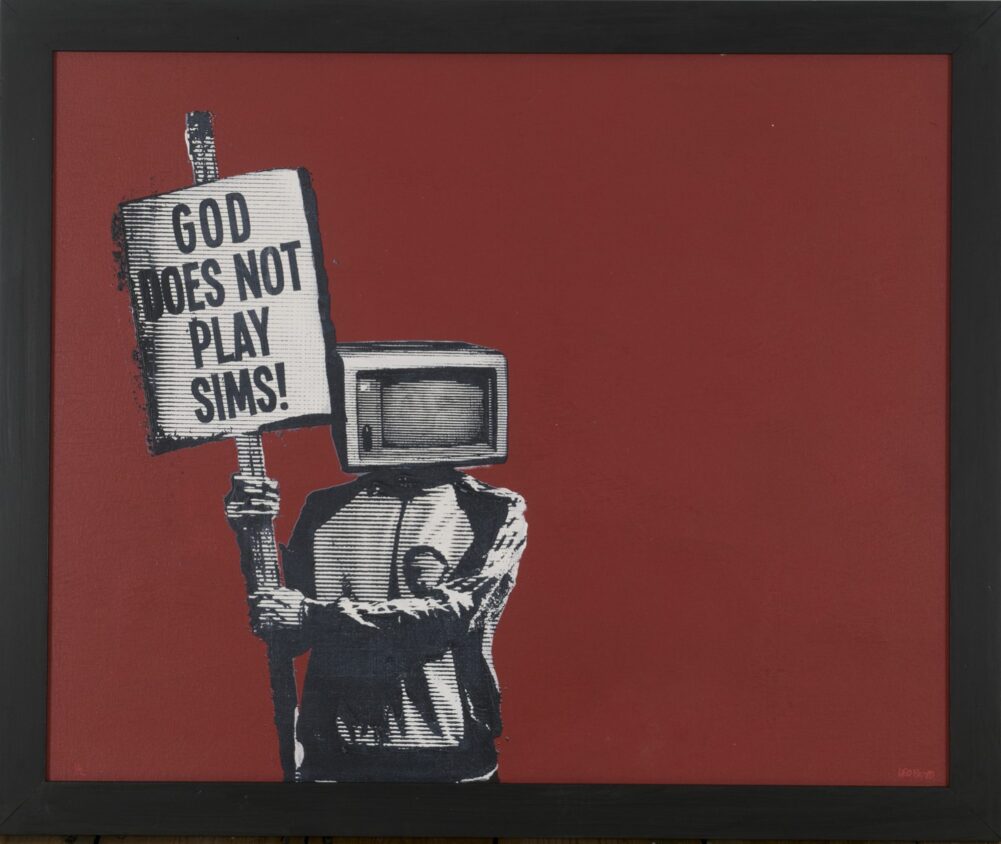

Boyd’s recent exhibition, ‘Welcome to the Simulation’, was presented at the small-scale commercial Atom Gallery, featuring paintings and prints that reference techno-utopianism, religious belief, political radicalism and retro advertising. Boyd’s titles clearly show an interest in puns, evident in a piece referencing agitprop titled Keyboard Warriors, or the Holy Mary with a heart emoji on her chest called Our Lady of the Emoji. This kind of punning isn’t limited just to artwork titles; it’s evident in how images are mashed up and used to communicate their message. When Mary’s sacred heart is substituted for a digital icon, it’s determinedly satirical, but also signals the relationship between technology and belief, contrasting an information economy with religious tradition.

Boyd’s artworks demonstrate a wide and varied assortment of gestures and marks. The flow between paint and print is fluid but controlled. It’s in this interrelationship that the works are at their best. When it’s just paint or just print, the works feel somewhat insubstantial; a little too small, with their surfaces failing to capture much attention beyond the visual gimmicks. Every artwork contains at least one character, and every character has a computer for a head. Sometimes this works to humorous effect, as in God Does Not Play Sims or Searching for Signal; the former shows a protester holding a sign with the titular phrase boldly printed on it, and the latter shows a huddled group of monks looking dramatically into the distance. Boyd’s work is weird and playful because of this, but can sometimes miss the mark, with the joke coming off a little too trite. Other moments feel adolescent in approach; one piece is a pixelated image of a Cézanne painting that is wholly out of touch with a generation of painters who’ve used glitch art to great effect, such as Enda O’Donoghue or Konrad Wyrebek.

While Boyd’s varied mark-making lends a kind of energy to his art, the far-reaching references in the works make the original premise feel quite flippant. There is a notable disconnect between the ideas of Nick Bostrom, the supposed premise of the exhibition, and what the artworks in question are actually addressing. Looking across the paintings and prints, we see religion, political movements, landfills, soldiers, gaming and so on. The series of references is so broad, it becomes incoherent. We could say that digital technology is so pervasive today that it has influence across all cultural arenas; that we can’t understand belief, power and consumption without it. But these notions are very far removed from specific points that Bostrom raises.

Contemporary art has an uneasy relationship with puns. What is gained in humour and accessibility, feels like a subtraction from the deeper meaning and dialogue found in a more ambiguous approach. Banksy might be the most established critical shorthand for a brand of street art that embraces both politics and humour. And while he may lack credibility amongst critics, he’s more than made up for it in mainstream popularity. In one sense, this isn’t surprising, as his street art borrows from and sits comfortably within the world of popular, accessible visual culture. One of the most interesting things about Banksy is this gap between his critical standing and his widespread popular appeal. The phrase contemporary art is not as broad as it seems, instead signalling a hyper-specific ecosystem of white cube galleries and the rolling series of art fairs and biennales that they participate in. Humour in art is always risking this gap.

Chris Hayes is an Irish art critic based in London and Assistant Editor with CIRCA Art Magazine.

Image Credits

Leo Boyd, God Does Not Play Sims, screen print and paint on plywood, 63 x 76 cm; image courtesy Atom Gallery