CHRISTOPHER STEENSON REPORTS ON SONORITIES FESTIVAL – AN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC AND SOUND ART FESTIVAL THAT TOOK PLACE IN BELFAST FROM 17 TO 22 APRIL.

If someone asked you where they might find a week-long, international festival dedicated to the latest developments in experimental music and sound art, you might recommend somewhere like Berlin. But since 1981, when Sonorities was founded at Queen’s University (QUB) as a “festival of twentieth century music”, Belfast has been just the place for an exploration of all things sonic. This year’s Sonorities Festival, which featured artists from over 40 countries, made a conscious effort to be more inclusive and open to the general public. By partnering with Moving on Music, the Belfast Film Festival and the club nights and labels, RESIST and Touch Sensitive, Sonorities was more widely-publicised and integrated within the city than it has been before, reaching beyond the festival’s usual academic circles.

Most of the programme revolved around music and performance, with emphasis on how new technologies can be used to augment the music-making process. This theme was variously explored through concerts in the Sonic Arts Research Centre’s (SARC) world-renowned Sonic Lab and during a one-day symposium, which focused on “techno-human encounters” in sound production, performance and composition. The opening performance, Re-Breather, by Franziska Schroeder, Jules Rawlinson and Dara Etefalghi encapsulated the festival’s reputation for daring experimentalism, comprising computer-generated visuals and the choked sounds of an electronically-treated saxophone, played without its mouthpiece. Other performances took place in Accidental Theatre, where highlights included Jon Kipp’s and Stuart Bowditch’s sound-sculpture performance, Fogou, and the slow motion body movements displayed by Federico Visi for SloMo Study #1.

In conjunction with Belfast Film Festival’s programme of screenings and events, festivalgoers experienced a different kind of audiovisual delight with a new performance by People Like Us (aka Vicki Bennett), titled The Mirror (2018). Working for over two decades as a multimedia artist, Bennett weaves together audio and moving image material to create collage-based works. The piece began with a chimeric soundtrack formed from cover versions of the song The Windmills of Your Mind (first made famous by the English crooner Noel Harrison). The lyrics to the song – which reference circles in spirals, wheels within wheels, turning carousels and tunnels – act as a roadmap for the recurrent imagery in the 40-minute performance. As the audience entered a hauntological world of Hollywood films and radio hits, a fractal and circular narrative was formed, whilst all the while being propelled forward by Bennett’s accomplished methods of live audio mixing. Other noteworthy video works included Fergal Dowling and Mihai Cucu’s surround-sound, fixed media piece, Ground and Background.

Sonorities also included an array of exhibitions and installations. In SARC’s basement-level Broadcast Room, the sound art collective Umbrella presented newly created multimedia works. Titled ‘Same Place’, the exhibition featured work by 11 members of the collective, who each explored different locations around Belfast and their related soundscapes. John D’Arcy’s North Street, for example, acted as a commentary on the Royal Exchange development that will see parts of Belfast’s historic North Street demolished to make way for a new retail area. In the video, D’Arcy walks along North Street with a virtual reality headset, intercutting his vantage point with simulations of a shopping centre. The open soundscape of North Street is contrasted with clinically-produced pop music, reverberating within the shopping centre’s enclosed environment, creating an amusing – if not bleak – future vision of the area.

Sonorities also included an array of exhibitions and installations. In SARC’s basement-level Broadcast Room, the sound art collective Umbrella presented newly created multimedia works. Titled ‘Same Place’, the exhibition featured work by 11 members of the collective, who each explored different locations around Belfast and their related soundscapes. John D’Arcy’s North Street, for example, acted as a commentary on the Royal Exchange development that will see parts of Belfast’s historic North Street demolished to make way for a new retail area. In the video, D’Arcy walks along North Street with a virtual reality headset, intercutting his vantage point with simulations of a shopping centre. The open soundscape of North Street is contrasted with clinically-produced pop music, reverberating within the shopping centre’s enclosed environment, creating an amusing – if not bleak – future vision of the area.

Other works on the grounds of QUB included John Kefala-Kerr’s Book of Bells in the Graduate School, whilst off-site there were exhibitions in QSS Gallery and Framewerk. As implied in the title, ‘Silent Sonorities’ at QSS inverted the general paradigm of the festival by focusing on the act of listening rather than sound-making. In one room, Iris Garrelfs’s project, ‘Listening Wall’ featured a selection of “listening scores”, encouraging visitors to engage with their auditory environment via several verbal and graphic instructions. The project is motivated by the isolationist stances that currently typify the modern political climate. In the context of Belfast’s Peace Walls and Northern Ireland’s continuing deadlock at Stormont, as well as a divisive focus on national borders in the era of Brexit and Trump, Garrelfs sees the ‘Listening Wall’ as a means of connecting people in the face of increasing threats of separation. However, the exhibition’s amateur presentation in the gallery, which saw pages affixed to walls with Blu-tac, could have been more refined.

In the second space at QSS was ‘SchuhzuGehör_path of awareness’ by Berlin-based artist Katrinem. Katrinem’s practice concentrates on sound and its relationship with space, which she investigates through performance-based ‘listening walks’. Originally developed in 2012 at Festival Klangstätten in Braunschweig, Germany, ‘path of awareness’ has since evolved into an international project with the artist recording her walks in various locations, including Marseille, Tehran, New York and, now, Belfast. Maps of these routes were presented on the gallery walls, while a video monitor with headphones, showed documentation of these walks, comprising video stills and binaural recordings, captured from Katrinem’s own ears, as she walked through the different locations. In these recordings, the artist’s “soundful shoes” act as a percussive focal point for the listener, revealing the material and spatial qualities of these environments and how they change as the walks progress.

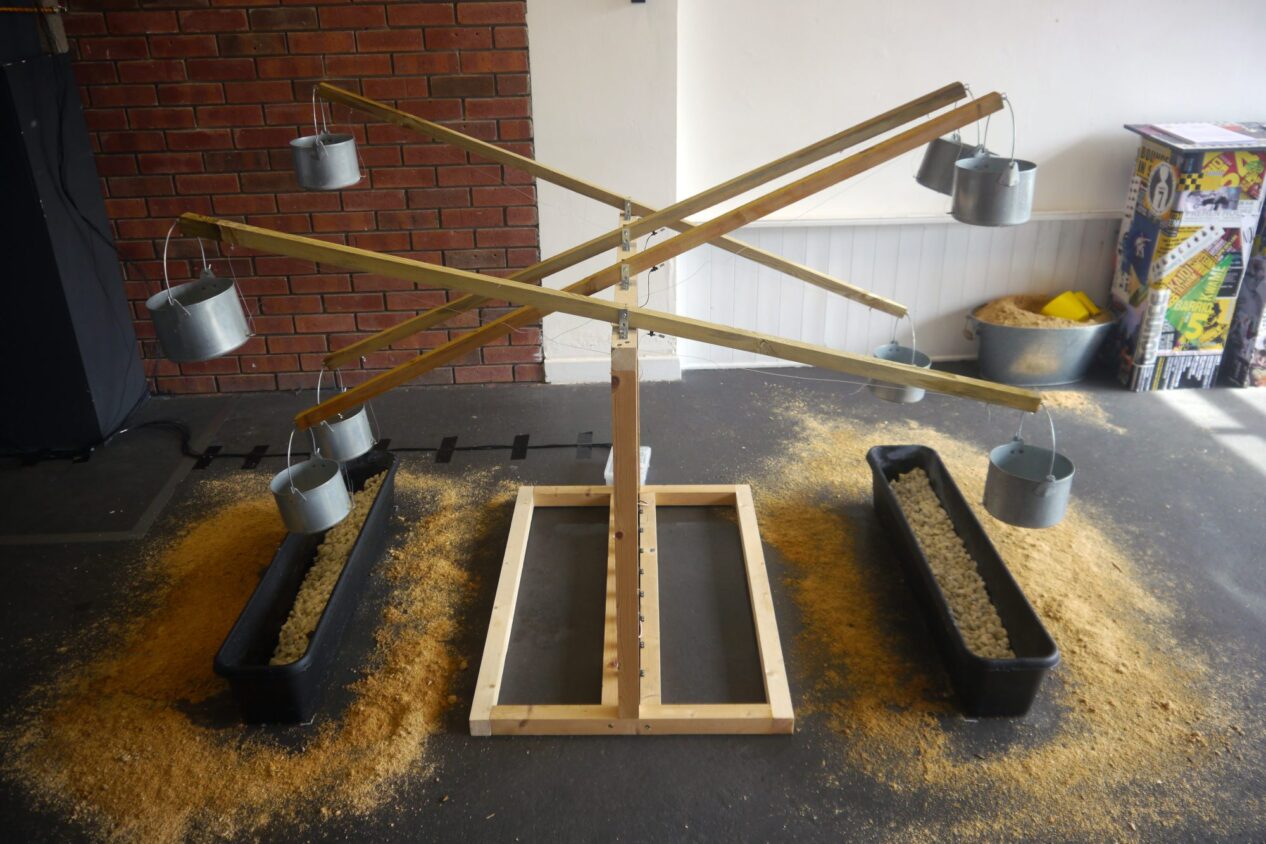

Glasgow-based artist Calum Scott’s sound sculpture, Scare the Deer, was shown at Framewerk in the east of the city. The work draws influence from the Japanese suikinkutsu sound-producing water ornaments and shishi-odoshi water devices, used by farmers to scare away crop-threatening animals. Taking these traditionally analogue modes of sound production, Scott’s sculpture also incorporated modern technology – such as Max software, Arduino boards and servomotors – to create a marvelously complex, yet graceful piece of work. Water dripped down into a set of metal buckets, creating delicate bell-like sounds. As the buckets were filled, they moved downwards and were tipped out, in a computer-coordinated dance. It was a highly meditative piece that invited prolonged periods of listening and viewing, proving to be a highlight of the festival programme.

The site-specific exhibition, ‘House Taken Over’, was curated by sisters Ciara and Nora Hickey. Taking place inside the curators’ family home in south Belfast, the exhibition was inspired by the discovery that the house was previously used as the Northern Irish Intelligence Headquarters during World War II. Logs recorded by a secret network of listeners across the country were forwarded to ‘Heathcote’ house, to be logged, before being sent on to code breakers at Bletchley Park. Lorcan McGeough’s parabolic sculpture, Swallow (2017), rose up from the lawn outside. Echoing the appearance of an ‘acoustic mirror’ (large, concrete structures used in WWI to detect the sound of approaching enemy aircraft), the work immediately suggested the presence of intruders. Its resemblance to a trumpet or a satellite dish seemed to imply that the secrets of Heathcote were finally being broadcast into the world.

The site-specific exhibition, ‘House Taken Over’, was curated by sisters Ciara and Nora Hickey. Taking place inside the curators’ family home in south Belfast, the exhibition was inspired by the discovery that the house was previously used as the Northern Irish Intelligence Headquarters during World War II. Logs recorded by a secret network of listeners across the country were forwarded to ‘Heathcote’ house, to be logged, before being sent on to code breakers at Bletchley Park. Lorcan McGeough’s parabolic sculpture, Swallow (2017), rose up from the lawn outside. Echoing the appearance of an ‘acoustic mirror’ (large, concrete structures used in WWI to detect the sound of approaching enemy aircraft), the work immediately suggested the presence of intruders. Its resemblance to a trumpet or a satellite dish seemed to imply that the secrets of Heathcote were finally being broadcast into the world.

Paintings, moving image works and sound installations – each toying with the ideas of military surveillance, radio communication and audio technology – were installed in different parts of the house. Searching for the artworks, visitors got the impression that they themselves were spies in search of lost historic objects. In the living room, Dorothy Hunter’s audio installation, Unofficial Secret (2013), softly announced itself from the fireplace, playing field recordings from a Cold War-era spy base in Berlin. Similar in content, Allan Hughes’s audio and video work, The Listening Station I (2008), was played on a video monitor in the downstairs bathroom, showing footage of the British army’s communications base, Black Mountain, in northwest Belfast. A concurrent soundtrack called out numbers, reminiscent of an intelligence war tactic. Meanwhile in the dining room, Colin Martin’s paintings, Stasi Museum II and Drum machine, visually referenced locations and technologies used for spying and music-making respectively.

Over the five days of the Sonorities programme, it was hard not to be overwhelmed by the sheer variety of work on display. From concerts to installations and insightful presentations, you might not have liked everything you encountered, but you certainly came away with a whole new appreciation of what the possibilities of sound can and will be.

Christopher Steenson is Production Editor of the Visual Artists’ News Sheet. He also practices as a sound artist.

Image Credits

Calum Scott, Scare the Deer, installation view at Framewerk, Belfast; image courtesy of the artist.

Stuart Bowerditch performing Fogou at Accidental Theatre, Belfast; image courtesy of Sonorities Festival.

John D’Arcy, North Street, 2018, video still; image courtesy of the artist.

‘House Taken Over’, installation view; image courtesy of Ciara Hickey.