JOANNE LAWS CONSIDERS SEVERAL PROJECTS COMMISSIONED FOR GALWAY 2020 EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE.

Though beset from the outset with every obstacle imaginable – from early resignations, rumoured deficits and weather-related postponements, to the full-blown catastrophe of pandemic and unprecedented global lockdown – Galway 2020 European Capital of Culture (ECoC) ended up delivering a timely panacea to the escalating inadequacies of the globalised art world. With COVID-19 bringing the planet to a standstill for more than half the year, many of the prescribed long-term benefits of holding the ECoC title – such as wider participation, social inclusion, or economic prosperity brought about by infrastructural investment and tourism – were either compromised, reduced or fundamentally unachievable. When such policy imperatives dissolve and fall away, what endures is simply the art – in this instance, a slower and embodied form of art, with the capacity to make us think more deeply about our current reality.

Deviating from the methodologies of other large-scale exhibitionary events – like global art biennales, whose cosmopolitan urban centres generally funnel the global art market – the abbreviated Galway 2020 programme extended far beyond the city. Where biennales tend to address the universal rather than the particular – often adopting modes of ‘world-picturing’ to articulate pressing global concerns – Galway 2020’s county-wide programme assembled a robust set of multidisciplinary projects that were either physically or conceptually embedded in their immediate landscapes. From towns and villages, to boglands and archaeological landscapes, the distinctive spatial character of the west of Ireland landscape was harnessed as an effective exhibitionary platform.

In journeying to remote places to view artworks, attend events or participate in workshops, audiences were exposed to many existing geo-cultural features – from the nuances of language and regional dialect, to the county’s deep-rooted maritime heritage and the slower pace of island life. Even the tumultuous weather patterns of the Atlantic coast proved memorable, shifting moodily across sublime landscapes. Described by Oscar Wilde as a “savage beauty”, Connemara was the setting for numerous projects, including a spectacular light installation in March by Finnish artist, Kari Kola. A thousand lights were installed across a five-kilometre stretch of Ceann Garbh mountain surrounding Loch na Fuaiche, illuminating the terrain at night with an electrifying aura of shimmering green orbs and indigo shafts. The spectacle was reminiscent of natural phenomena, such as the Aurora Borealis, or bioluminescence – the emission of light by living organisms. In Irish folklore, atmospheric ghost lights seen by travellers at night – commonly cited as levitating around ringforts, bogs and woodlands – were often attributed to elemental spirits and fairies. A descending shroud of fog further enhanced the atmospheric conditions of Kola’s Savage Beauty, which was also dramatically reflected in the still lake below. The light installation was originally intended as a public event, to be presented from 14 to 17 March; however, due to public health restrictions, it had to be reconfigured as a film and disseminated online. Happily, the aerial footage shows a steady flow of traffic along the lakeside, with locals experiencing private viewings, as they drove past in their cars.

Another important manifestation of slow art encounters in the landscape was ‘Aerial/Sparks’, a well-conceived and ambitious interdisciplinary project, developed by artist Louise Manifold, in partnership with the Marine Institute. Seven artists, writers and composers from Ireland, Germany, England and Slovenia participated in research surveys onboard the Marine Institute’s Celtic Explorer, a multipurpose research vessel with sonic capabilities. During these expeditions, artists worked alongside scientists monitoring biodiversity in the ocean wilderness. Acoustic and audio-visual works, inspired by the ocean environment, were exhibited as an art trail on Inis Oírr from 11 to 27 September.

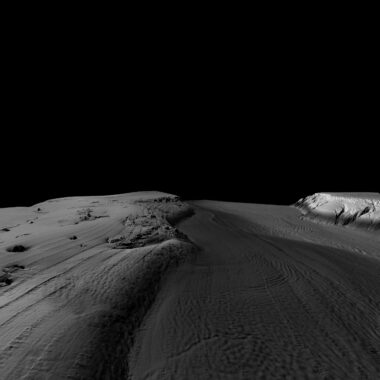

The hour-long ferry crossing from Rossaveel to Inis Oírr tentatively echoed the nautical experiences of the artists onboard the research vessel. This pilgrimage into the wilderness was worthwhile; viewers were invested from the outset, with their journeys becoming part of the art encounter. Upon arrival, most visitors traversed the island on foot or by bicycle, following the art trail, which distributed artworks across the island. Manifold wanted to keep space for thinking between artworks, describing Inis Oírr as “a place rich with silence” where “sounds are carried on the wind.” Inis Oírr Church was the site of Slovenian artist Robertina Šebjanič’s audio installation, comprising field recordings taken above and below the sea, with narration channelling the seanchaí and sean-nós traditions. Similarly, German composer David Stalling’s mesmerising audio-visual soundscape, Palace of Ships, was installed in a former handball alley. The installation combined footage and field recordings of turbulent sea conditions, in which seismic data was reconfigured to emphasise its musicality. Several works were also presented in Áras Éanna, the island’s only dedicated art space. Carol Anne Connolly’s seductive series of monochromatic Giclée prints, Answering Echoes, was dramatically spot lit in a darkened room, the grainy, lunar-like landscapes revealed as images of the ocean floor, generated through acoustic mapping.

Continuing themes of cultural embodiment explored in their individual practices, artist duo Kennedy Browne’s crisp new video work, Island Affinities, shows improvisation by Gearóid and Colm Devane, fifth generation sean-nós performers from Connemara. They dance and play accordion against a backdrop of crystal-clear water, upon a ruined US military vessel, recently washed up on the shore. Magz Hall’s installation, Waves of Resistance, comprised wall diagrams and a looped sonic work transmitted via six radios. Centred around a kitchen table, it recalls the DIY aesthetic of pirate radio1 as well as the domestic setting to which we have all been recently confined. Presented in Áras Éanna’s snug theatre space was Ailís Ní Ríain’s hypnotic video and melodic sound composition, East-West, featuring footage taken through her cabin porthole – described by the artist as a “solitary and limiting, yet limitless viewpoint”.

Inis Oírr Lighthouse is normally closed to the public, but generously welcomed visitors for Kevin Barry’s Island Time, a site-responsive nine-part monologue presented as a two-channel video.2 A lighthouse keeper, tormented by isolation, unrequited love and the phases of the moon, speaks of “presences in the fields, unseen by the naked eye” and “unknown stray dogs losing their reason”. He likens the 3am to 7am shift to “crawling across Siberia”, preferring instead the calmer 11pm to 3am shift, when the night is “as blameless as a small child” and “as quiet as the boneyard” – perhaps an affectionate nod to the late Tim Robinson’s exquisite book, Connemara: Listening to the Wind. Occasionally, the keeper’s mind follows the lines of distant ships to the ports of Cairo, Vancouver, Genoa; but in reality, he never sees further than the cold damp cliffs of Clare.

Continuing a focus on island life, ‘MONUMENT’ at the Galway City Museum assembles a rather poetic inquiry around stone monuments situated on small islands. Featured in the exhibition is previously unseen material from the 1990s archaeological excavation of the Dún Aonghasa – a prehistoric hillfort on Inis Mór – alongside other cultural artefacts and oral histories. Several new commissions are presented, including filmmaker Colm Hogan’s striking 15-minute film, which captures the unique physical and cultural landscapes of the Aran Islands. Also situated in Connemara, ‘Culture Horizon’ in Clifden was developed as part of ‘Small Towns Big Ideas’ – Galway 2020’s county-wide community programme, assembled around the old Irish term, Meitheal. Clifden is officially twinned with Coyoacán, a culturally rich municipality of Mexico City, where Frida Kahlo’s family home is located. A Frida Kahlo exhibition, as well as installations, performances and a candlelit vigil, formed part of a festival in Clifden, aimed at celebrating cultural connections between Ireland’s Samhain traditions and those of Mexico’s Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead).3 Another highlight of ‘Small Towns Big Ideas’ was the Headford Lace Project, which involved the commissioning of a permanent artwork by artist Róisín de Buitléar, to honour and celebrate the town’s lacemaking heritage, alongside a popular series of craft workshops, tours and an art trail.

Irish artist, John Gerrard, is best-known for his ambitious digital simulations that use real-time computer graphics. Gerrard was commissioned by Galway International Arts Festival to develop two new artworks for Galway 2020 ECoC, originally intended to be presented consecutively in dual locations: Mirror Pavilion, Corn Work was installed in Galway City from 3 to 26 September 2020; while Mirror Pavilion, Leaf Work was scheduled to be shown in Derrigimlagh Bog from 11 to 31 October. However, the second phase has since been postponed until March 2021. Gerard’s team combined 3D scanning technology with meticulous hand-rendering to create algorithmic portraits of these sites, which took over two years to complete. A pavilion structure was designed to host both artworks, clad in polished metal and fronted with a high-resolution LED wall. This futuristic-looking cube was installed on Galway’s Claddagh Quay – the site of one of Ireland’s earliest fishing villages (dating from the pre-Christian era) later associated with eighteenth-century industrialists who harnessed the River Corrib to power dozens of corn flour mills, once installed along the riverbank. However, rather than an incongruous presence, the shimmering, seven-metre-tall structure felt strangely of this place.

Mirror Pavilion, Corn Work featured four mysterious folk figures, who perpetually performed in circular configurations, echoing the phantasmagorical water wheels that once powered the city. Clad in straw suits and headpieces, these anonymous characters appeared to be physically subsumed by the material landscape that once sustained them, while also recalling the rural Irish Straw Boy tradition, whose ancient dances and fertility rituals have druidic origins. The character’s anonymity conjured a supernatural presence – a sublime yet unsettling encounter that was further confounded by their posthuman scale, regal posture and slow glide across the screen. This hypnotic choreography was originally undertaken by real dancers, wearing wireless sensor motion suits to transform their performances into ‘databases of motion’. Assuming that COVID-19 is a food-born virus, it seems fitting that Mirror Pavilion, Corn Work would memorialise an era prior to the advent of petroleum-based energy and intensive conventional farming – described by the artist as a ‘hyper-violent machine’, deadly to all other forms of life. A more sustainable past was channelled without nostalgia and pitched against our present reality, reflected in the mirrored structure, to jut against and make a continuum with the horizon.

As COVID-19 continues to halt the planet, it also arrests the global flow of artists, artworks and audiences, while making visible the structural apparatus and economies of labour that underpin the production of art. This was especially pronounced at the microlevel of the island, where nothing can be done simply or quickly, and everything needs to be shipped on or off. The embodied art encounters delivered by Galway 2020, punctuated a time when people began to question their priorities and adjust to a slower pace of life. Due to ongoing lockdowns, many projects were largely experienced by local or regional communities, in contrast to the specialist art audiences or cultural tourists that generally descend on events of this scale, accelerating the default inequalities of overtourism. With traditional evaluation methods now rendered untenable – like visitor numbers, hotel bookings and other statistical data – it would be interesting to know whether a more narrative framework could be assembled, to gauge the impact of these projects, particularly for local communities, who know these landscapes intimately.

Joanne Laws is Features Editor of The Visual Artists’ News Sheet.

Notes

1 A named example was Women’s Scéal Radio, broadcast by activist and performance artist, Margaretta D’Arcy, in Galway from 1986–88.

2 Rumour has it that the monitors came from a police station in Birmingham, where the Birmingham Six were interrogated.

3 At the time of writing, the festival in Clifden was scheduled to take place from 23 October to 1 November.