Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

25 October – 7 December 2019

Speaking on Luke Clancy’s ‘Culture File’ on RTÉ Radio 1, Eoin Mc Hugh offered ‘Loje, Jelo, Laso’ (Red, Yellow, Blue) as straightforwardly phonetic, like all of the words in Toki Pona, a philosophical language invented – believe it or not – to make things easier to understand.1 McHugh’s titles have previously referenced poetry and psychoanalysis, in an oeuvre rich with allusions to both. Clearly interested in language and how it relates to our perception of art, he complicates things considerably here by choosing titles – our traditional access points – every bit as esoteric as the images themselves. Maybe that’s the point. Approaching an image through familiar language inevitably alters our perception; we see the image overlain with language, we ‘read’ it, and perhaps the artist wants to confound this tendency by presenting us with words we don’t understand.

Mc Hugh’s previous Kerlin show (‘The Skies Will Be Friendlier Then’ in 2014) was commanded by an ungainly black beast. Unearthed from some despicable ground, the hybrid figure was both threatening and oddly vulnerable. On the walls nearby, two Persian carpets had been stripped of their woven logic and touched-up with a kind of analytic violence. The air in Toki Pona land is less fraught. Paintings and drawings – there are no scary sculptures here – are divided equally between framed and unframed, abstract and figurative, colour and black and white. The anxious air of old has been replaced with an idea of order.

Seven small oil paintings are equally spaced along the gallery’s north flank. Of similar size and treatment, their colourful surfaces are smooth and blurry, like out of focus night scenes or botanical details too close for the eye. Of course they might be just paint, ordered by intuition and formed into pleasing abstractions. Introducing them, the gallery press release states that: “Research and source material are largely bypassed in favour of experimentation and direct expression…” This might be applied to any number of painting practices, and is difficult to square with Mc Hugh’s previous habits of allusion and metaphor. Of course things change, but their sense of a probing, underlying restlessness suggests these paintings are less about experimentation than a world waiting to be born, hovering on the brink of comprehension.

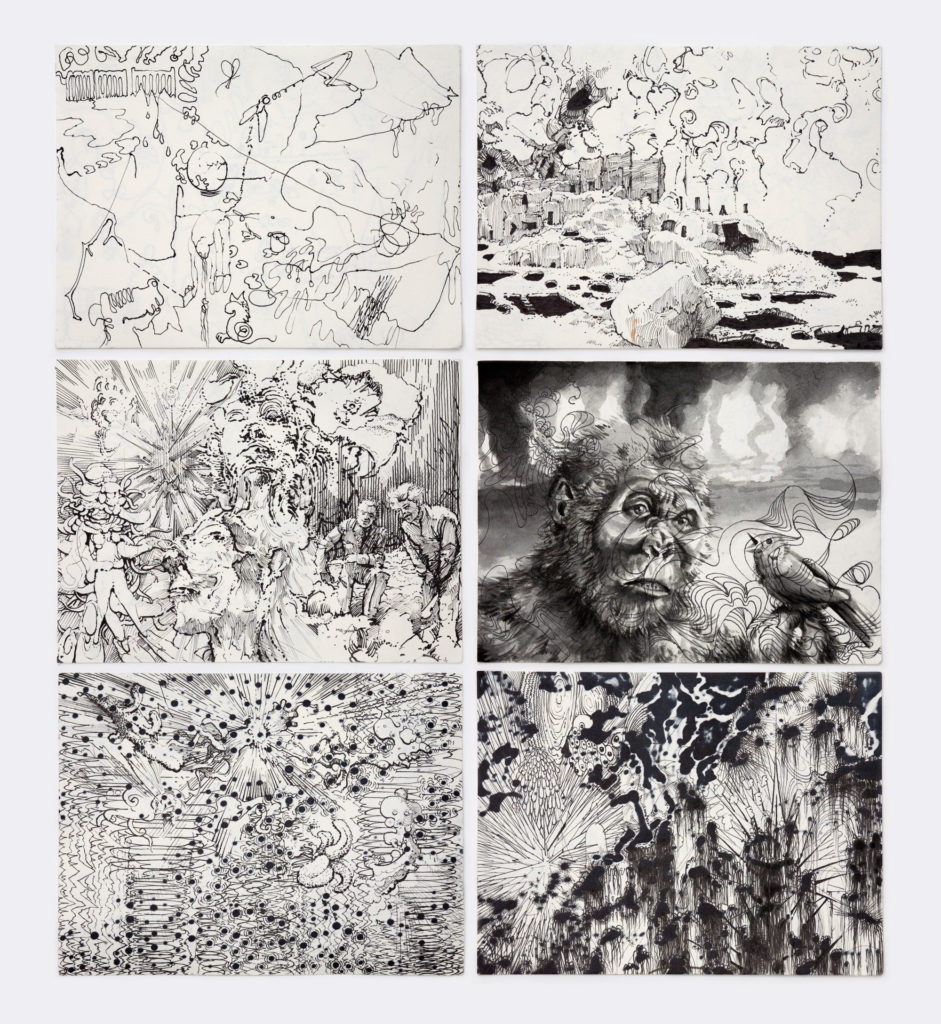

On the opposite wall, a series of more than 100 black and white notebook drawings are displayed in a row of elegant, white frames.2 Hinged so they sit out from the wall, each frame carries two sets of six drawings arranged in neat grids on opposing sides. Made during and after therapy sessions, the pages have a doodling, obsessive quality, with birds, human figures, and other, freakier creatures, all set amidst explosions of marks and lines. Here and there words appear – ‘floating’, ‘glowing’, ‘nerves firing’ – and these, along with the serial format, bring comic books to mind (and zines, á la Raymond Pettibon, for instance). A grander imaginative leap might take us to Goya, and his etching series, ‘Los Caprichos’ (1799). An early comic book of sorts, the most talismanic work from that set, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, would feel perfectly at home here.

Mc Hugh is a gifted draughtsman, adroitly capable of making even the most outlandish scenarios seem, if not exactly natural, at least on the brink of credibility. In a separate, larger drawing, called Orzchis Caldemia, a bald and naked man sleeps beneath an orgy of spiralling figures and abstract shapes. While he sleeps, his erect penis, topped with a miniature version of his own head, appears distinctly awake. This miniature knobhead is, in turn, a platform for a tiny songbird, one of a myriad of avian creatures (some with penises of their own) swirling within the centrifugal image. In an additional twist, the entire scene appears to be emanating from the eye sockets of a ghost-like, human skull. A previous work by Mc Hugh, Little Hans Nightlight (2014), with its light projecting eyes, seems a forerunner to this macabre image. I’m also reminded of John Ashbery’s long poem, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, where the poet describes a captive soul, restless to go further than the eyes can see. “But how far can it swim out through the eyes”, he asks, “And still return safely to its nest?”

John Graham is an artist based in Dublin.

Notes

1 First published in 2001, Toki Pona (‘Good Language’) was invented by Canadian linguist, Sonja Lang.

2 The series of drawings is collectively titled ‘io’, from the aUI language, invented by W.J. Weilgart as an aid to psychoanalysis.

Feature Image: Eoin Mc Hugh, Orzchis caldemia, 2018–2019, acrylic ink and watercolour on paper, 56 × 72.5 cm; courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery.