Gallery of Photography, September 9 – October 22

The result of the 2016 British referendum on the future of European Union membership has brought about a new era of social and political anxiety regarding the border between the Republic and Northern Ireland. ‘Brexit’ is a neologism that has been mobilised by ultra-conservative politicians and sections of the British media alike, to portray what was in reality a marginal ‘yes vote’, as the inevitable political expression of the zeitgeist of British isolationism and nationalism. On the island of Ireland, Brexit has resurrected the spectre of the border which has haunted Irish politics for nearly a century. Kate Nolan’s exhibition ‘Lacuna’ at the Gallery of Photography explores everyday experiences of the border through the local inhabitants of Pettigo, a small town in County Donegal. This body of work emerged in the midst of political speculations about Brexit, including the potential hardening of the border between north and south.

Nolan’s recent body of work was not produced as a reaction to Brexit’s revival of the border as a prospective geographical and ideological barrier; rather ‘Lacuna’ emerged in the midst of the psychological ‘anxieties of place’, engendered by the shadowy presence of Britain’s exit from the European Union on the not-so-distant future horizon. This distinction is important because the cultural weight of Brexit (and its pervasiveness in the discourse of European affairs) can obscure the more nuanced experiences of border life explored in this exhibition.

Looking at Nolan’s exhibition solely through the prism of Brexit would limit the artist’s investigation of the everyday realities of border communities. Importantly, place, border and geographic location are not abstract concepts; they are lived out through the everyday experiences of the individuals who dwell and labour in the interstitial spaces between the neat geographical borders that demarcate north from south and vice versa. Indeed, as the centenary of the 1921 partition of Ireland approaches, ‘Lacuna’ may become a precursor to wider investigations of other border locations.

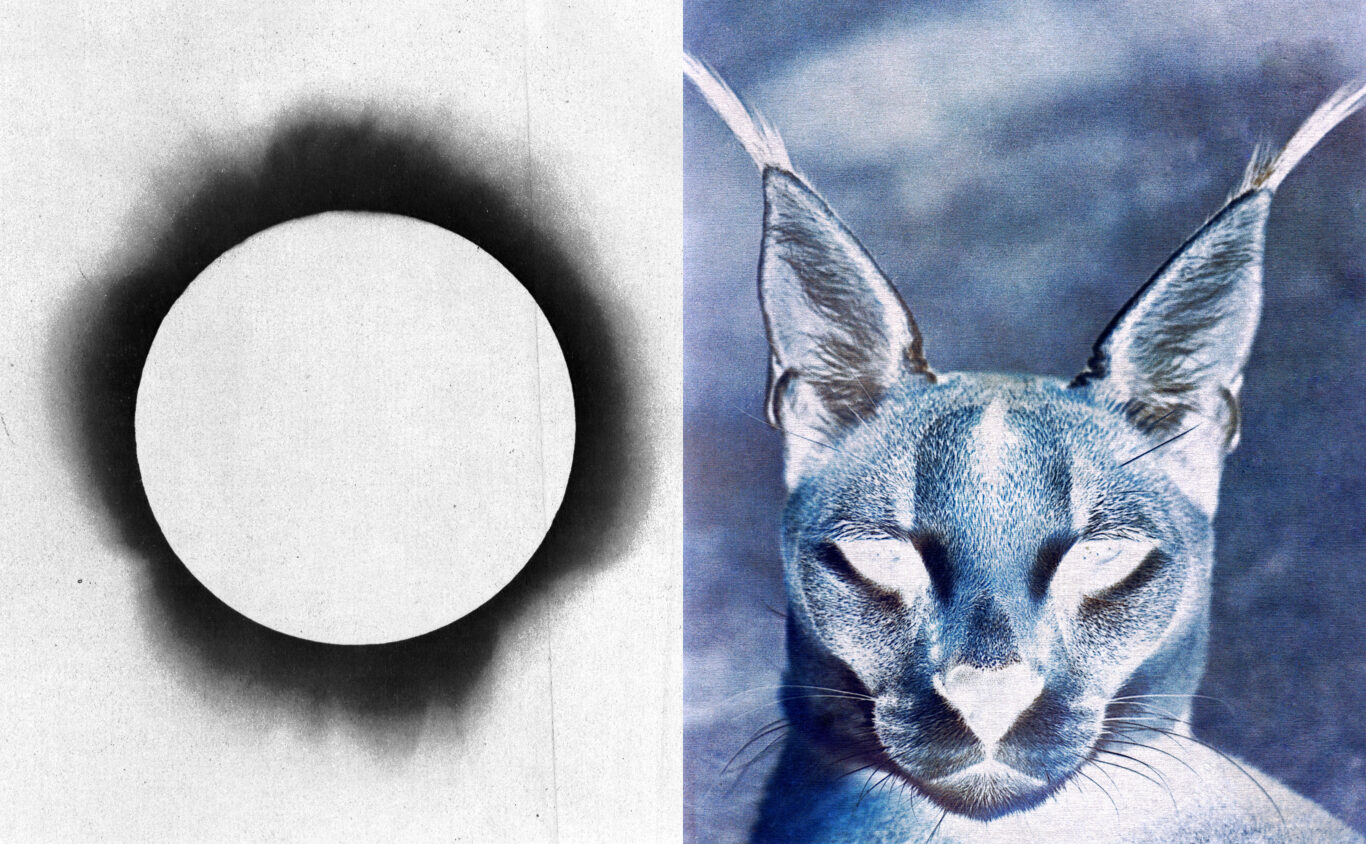

The exhibition comprises several photographic and audio-visual works including: two large-scale colour portraits; photographs of landscapes and the built environment, including detailed depictions of fauna and water; an audio recording of an adolescent girl who describes a typical Friday night; and a three-screen audiovisual installation with an accompanying sound piece composed by Gavin O’Brien. Nolan’s visually distinctive installation focuses on the shifting momentum of Termon River, which divides the town and functions as the border between the Republic and Northern Ireland. Three monochromatic projections animate the light against swaying conifer tress. What coheres this audiovisual installation to the other works in the show, is a sound recording of an adolescent girl describing her journey to the local chip shop. These deceptively simple descriptions of mundane events are highly effective in conveying how ‘place’ is enacted through the daily routine of traversing the border.

The various artworks are interspersed with wall-mounted textual inscriptions, drawn from stories recounted by Pettigo inhabitants. While these statements are not attributed to specific individuals, their dispersal throughout the exhibition prompts the viewer to make connections between the photographic works and the community’s experience of the border. However, the anxieties created through the possible imposition of a ‘hard border’ are not directly expressed in this exhibition. Instead, the artist focuses on the mundane aspects of daily life, evidenced in stories about the practicalities of school bus journeys, visiting friends or relatives and the delivery of take-away food. Combined with Nolan’s two large portraits of an adolescent girl and boy, photographed against a densely wooded backdrop, these textual descriptions convey the everyday ‘lifeworlds’ of communities – a subject that has increasingly permeated Irish photography over the last decade. Such work has been characterised by photographers engaging in ‘empathetic insideness’, to borrow a term from Canadian human geographer Edward Relph. In other words, these artists present a sustained ‘seeing into’ and appreciation of place as lived experience.

The bodily disposition of Nolan’s two young subjects in these large-scale portraits, coupled with the absence of formal codifications of portraiture, emphasises an awareness of how place and identity are intertwined. However, it is the audio piece of the adolescent girl – who relays her knowledge, experience and familiarity of her locality, through a habitual Friday night trip to the local chipper – that provides the most powerful evocation of place. On her journey, landmarks are named, residents are identified, history is recalled, and before the chipper comes into view, “the sweet sting of vinegar” awakens the young narrator to her position in the everyday ‘lifeworld’ of this small border town.

Justin Careville is a lecturer in Historical and Theoretical Studies in Photography at the Institute of Art, Design & Technology, Dún Laoghaire, where he is also Programme Chair of the BA (Hons) Photography Programme.

Image used: Kate Nolan, Untitled, 2017, photographic print; image courtesy of the artist.