Draíocht Arts Centre, Blanchardstown

14 March – 18 May 2019

Immediacy, I’ve found, has always been an underlying characteristic of much contemporary painting. I’ve never tried to pull back the curtain of the canvas, in search of hidden meaning lurking beyond sight. Surely, I thought, there is no code to crack; what you see is what you get. However, this limiting preconception was unilaterally turned on its head by ‘MAKing Art:PAINTing’. Sitting with the paintings in this group exhibition – which includes work by Susan Connolly, Bridget Flannery, Geraldine O’Neill and Liz Rackard – I found nostalgia, warmth and physical engagement seeping out.

‘MAKing Art:PAINTing’ is the second instalment in a series of exhibitions tailored to the general public and young people. Speculating that this exhibition may have an ‘educational agenda’ (as I’ve seen in previous shows), I did not expect to encounter work that would showcase the true scope of Irish contemporary painting. In fact, the opposite is true.

Liz Rackard’s small-scale portraits of family and friends read like a family album, however they are not necessarily the kind of photos you would display above the fireplace. Two acrylic works on paper, Big Sleeper (2016) and Little Sleeper (2016), detail anonymous figures during moments of rest. These scenarios recall the mental image we all have of loved ones relaxing after a long day. The tenderness of these images and their intimate scale draws us into the frame and into the warmth and comfort of these private domestic moments. Such delicate reminiscence is stripped bare in Bridget Flannery’s painted panels. Rather than languorous figures, we are shown rugged abstract landscapes, painted vibrantly with expressive brushstrokes in muted pastel shades. Across Clearings (2018) embodies atmospheric natural hues, textures and materials at the contracting methodical scale. Flannery’s physical expression of memory and place seeps pungently into the wood, which acts as a support for this work. Rather than formal paintings, Flannery’s compositions feel as though they have been chiselled out of a dreamscape, like organic segments cut and pasted onto the gallery wall.

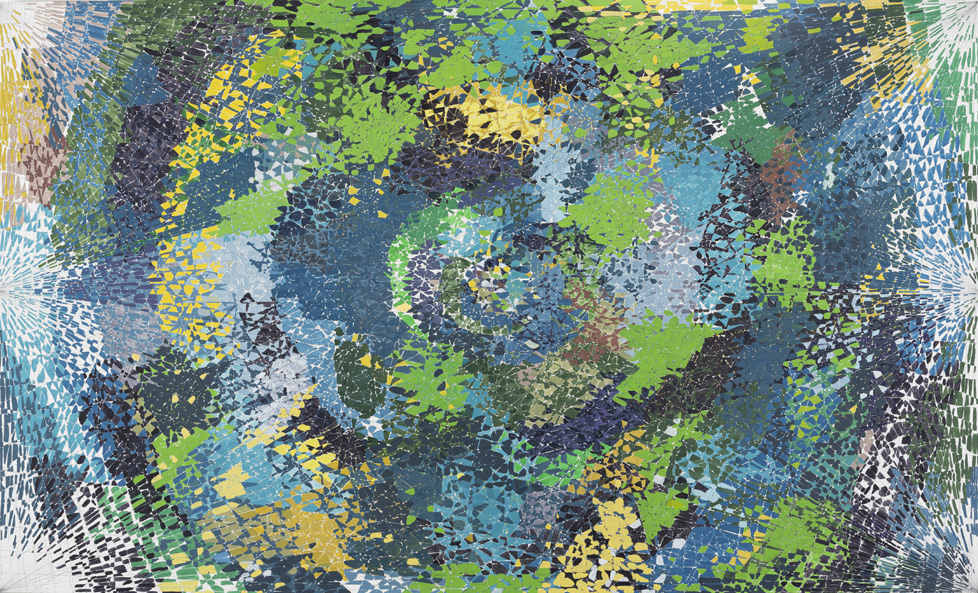

On the opposing wall, three works by Geraldine O’Neill lean into the art historical cannon of realist painting. O’Neill’s compositions appear to take influence from seventeenth-century Dutch Still Life and other prominent movements throughout the history of painting. And yet, the work feels extremely fresh because it is permeated with modern cultural references, including the vibrant pink and orange outfit of Dora the Explorer, depicted in Mouse Trap (2010). This scene is so meticulously painted, that we can almost hear the synthetic rustling of the ever so slightly deflated, crinkled balloons. In addition, the rich green Irish football jersey, depicted in Boy (2008), is instantly recognisable. This painting depicts her own son against a vast and barren landscape, providing a seemingly outdated backdrop for the uncanny aura of youth.

The stand-out work – quite literally – was Susan Connolly’s large-scale, installation-based painting. The artistry of Connolly’s oeuvre does not lie her in subject matter, but in matter itself. It is her layering process and her unapologetic treatment of materials that translates the work into three dimensions. For example, Ymc-iridescent (2019) invites us to shift from viewer to active participant. Our perspective moves from outward to inward, as we venture between the fixed blue wall and the back of the canvas. As we move, the shadow cast by the intricately arranged panels traverses the body, momentarily transforming it into a light-painted surface.

Overall, the experience of each body of work is heightened by curator Sharon Murphy’s gentle consideration, which allows autonomy to emerge between each cluster of paintings, while encouraging the viewer to follow each surface throughout the space. This diverse range of painting practice is further supported by a strong concurrent exhibition taking place in the First Floor Gallery, which showcases paintings from the Arts Council Collection. Spanning a 50-year period (1968–2018), this choesive selection of paintings range from Roy Johnston’s minimalist yet sculptural Sixteen Rotating Forms (1975) and the vibrant parallel brushstrokes of Diana Copperwhite’s Argentina (2006), to Damien Flood’s delicately restrained and considered approach to subject matter in Parting (2016). No cultural object can retain its value without consistent viewing by new audiences. This makes the regular showcasing of works from the Arts Council Collection ever more important.

Sara Muthi is a writer and researcher based in Dublin.

Feature Image:

Geraldine O’Neill, Mouse trap, 2010, oil on canvas, 130 × 180 cm; courtesy of the artist and Kevin Kavanagh Gallery.