CURATOR DANIEL BERMINGHAM INTERVIEWS ARTISTS EIMEAR WALSHE AND EMMA HAUGH ABOUT THEIR RECENT EXHIBITION, ‘MIRACULOUS THIRST’, AT GALWAY ARTS CENTRE (5 – 25 MAY).

Daniel Bermingham: The exhibition title, ‘Miraculous Thirst’, is a totem for shameless desire, in the face of personal sexual trauma. During the development of your show, Ireland responded to a particularly violent period of national sexual trauma. Can you discuss the relationship between personal and collective trauma?

Eimear Walshe: Coming from the online lexicon, ‘thirst’ is a playfully condemning word for shameless displays of queer desire. I use ‘miraculous thirst’ to describe persistent, undisguised desire that has been suppressed, under whatever personal or systemic regime. Such desire should not exist – especially in the context of the dystopian legal, medical, political and sexual landscapes that we’ve been subjected to in Ireland – but somehow it still does. It’s painful to acknowledge how intertwined national and personal sexual traumas are. I think it’s appropriate to name a lot of the desire that I see around me in Ireland as ‘miraculous’. Personally, I’d beatify many of my friends and lovers for not just going on sex-strike over it.

DB: I’m curious how some of your artworks operate. You used gay men’s literature in the performance, Sex in Public, and incorporated the body in Clothes for Queer Cruisers, denoting a ‘dyky land reclamation’ of the male cruising area of the Teufelssee in Berlin. Is this an intentional reclamation of queer history from cis gay men1?

Emma Haugh: I would say that the borders here are quite amorphous; it’s a bit of a trickster move that marks desire and sexuality as a terrain that can be shared. It took me some time to unravel the implications of these appropriating actions for myself. I understand them more and more as a performative questioning of identity, ownership and spatial politics in relation to history. I don’t so much propose to reclaim history – or the future – from gay men; I propose that I am already there and perform an alternate narrative of visibility.

DB: How do you see the role of our individual queer histories (dyke, non-binary, trans, cripple, fag, poly, bi) and does this inform a certain hybrid futurity in your work?

EW: I think those histories were central; the show integrated and emphasised a set of united interests, without ignoring difference. There were a lot of shared motifs in the work and common reference points. Snakes were recurring figures, so, in a serpentine fashion, I think of our work as picking up where the other leaves off. For me, the exhibition facilitated a different type of thinking – thinking with agency around desire and thinking with hope – making space for futurity in queer discourse without centring reproductive futurism.2

DB: ‘Miraculous Thirst’ touched on the overlapping discourses of queer theorists, José Esteban Muñoz, Gloria Anzaldúa and Kathy Acker. Did these textual inclusions amount to a homage?

EH: I would say it’s more of a presence. The desire was to bring these people and their brilliant work together and to acknowledge, through dedication and remembrance, their importance in queer world-making practices. I would say it’s also a citational act of love, to stay close to the voices of those who inform our work.

DB: You have previously spoken about the “obviousness” of work that speaks for itself. Can you discuss your desire and intent?

EW: I think I’ve been using ‘obviousness’ as another way of speaking to what might be euphemistically be called ‘visibility’. Obviousness is a way of psychologically grappling with what’s implicit in an artwork, regarding the extent to which work reflects its author. In the same sense that ‘thirst’ implies some kind of ‘indiscreetness’, I wanted the sculptures to be flirtatious or wanton in some way. Take for example the word, ‘Middle Spoon’, which was rendered in pink cursive neon on the gallery wall. You can interpret that as a proposal, in the sense of a neologism, or as a proposition, maybe even a personal ad! Or as an idle fantasy, a threat to society – inclusion gone too far, or not far enough, depending on what you project. In the spirit of indiscreetness, I’d say the works are also a retort to two classic harassment slogans: “Do you have to advertise it?” and “Get a room!” The collective works answered “yes!” and “no!” respectively.

DB: Your performance, Sex in Public, (which took place on 5 May as part of the exhibition) used self-described “theory poetry”, comprising the quite slippery use of language. I want to say this was an attempt to establish a future queer language, but what informed it?

EH: This was directly informed by Kathy Acker saying that she wanted to increase possibility and her own pleasures within her writing – a process that involved her use of reappropriated, plagiarised texts. I wanted to try this method as a means of loosening control and rigidity within my own writing practice, so that multiple voices and histories could be channelled through the avatar of my performing body. I find it interesting that an audience so easily ascribes the spoken experience to the speaking body – I enjoy playing with this device. The texts have been appropriated form literature written by gay men describing experiences of sex in public, and also from theory dealing with sexual politics and public space. They all come together with me as the channel, with my own desires being loosely woven between the reappropriated words.

DB: We have proposed a certain open-ended futurity for the show and artworks. Where do you see this afterlife enacting itself?

EW: The exhibition operated around the idea of an ever-expanding horizon of hope, I think. For me, that’s ongoing work – involving making and learning new vernaculars in language and images – and I see this already manifesting in the aftermath of the exhibition. I remember the first time I saw a show by Emma Haugh; it left a pressing question in the back of my mind, one that’s still unresolved. That’s a real gift. I’m really glad we got to show together, and hopefully these works meet again in the future, to perform some more miracles.

Eimear Walshe makes sculptures, writing and research with a focus on queer theory and feminist epistemology. Walshe is research fellow at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven and will initiate The Department of Sexual Revolution Studies.

Emma Haugh is a visual artist and educator based in Dublin and Berlin. She is interested in reorienting attention in relation to cultural narratives and develops her work from a queer/feminist/working class questioning of what is missing? She is co-founder of the performative publishing collective, The Many Headed Hydra.

Daniel Bermingham is a curator based in London. Bermingham is interested in publicness, community space and pedagogy, particularly with regard to intersectional queer and crip audiences.

Notes

1 As a prefix, ‘cis’ refers to the term ‘cisgender’, denoting people whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth.

2 The term ‘Reproductive Futurism’ was developed by American academic, Lee Edelman, to describe the tendency to define political value in terms of a future “for the children”, insisting that the power of queer critique is in its persistent opposition to this narrative and, therefore, to politics as we know it. Edelman argues that to be queer is to oppose futurity. See – Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004).

Image Credits

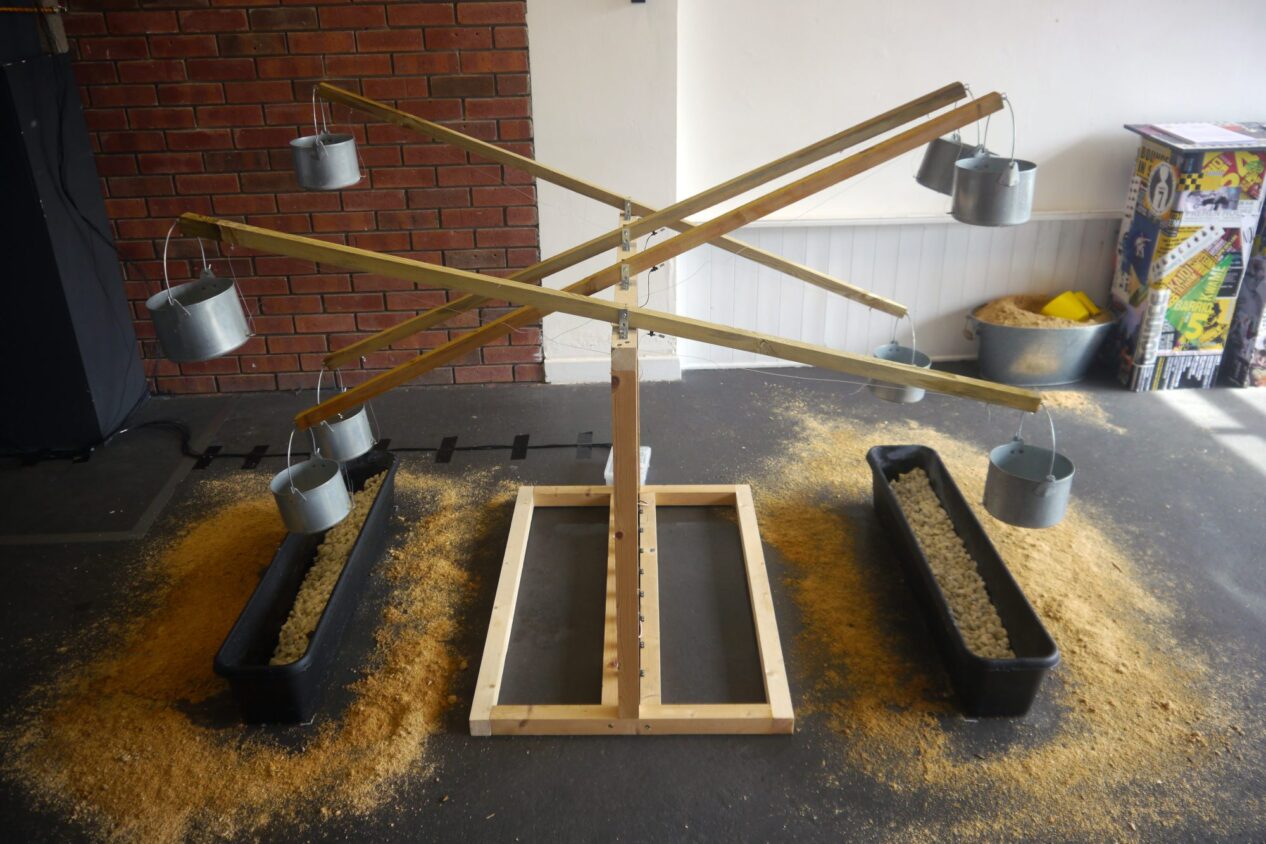

Eimear Walshe and Emma Haugh, ‘Miraculous Thirst’, installation view, Galway Arts Centre, mixed media, dimensions variable; photograph by Tom Flanagan.

Eimear Walshe, Middle Spoon, 2018, neon, 130 x 30 cm; photograph by Tom Flanagan.