SARA BAUME INTERVIEWS DOROTHY CROSS ABOUT HEARTSHIP AND OTHER RECENT ARTWORKS.

In February 1999, the ghost of a small ship appeared in Scotsman’s Bay. It returned every night for three weeks, glowing on into dawn, fading as the hours passed and revealing itself, in daylight, to be a decommissioned lightship called Albatross, which had been covered in phosphorescent paint and moored to the spot. Its protracted presence off the coast of Dún Laoghaire has since become one of the defining works of contemporary Irish art, as well as the stuff of urban folklore.

Twenty years later, on a glittering afternoon in September 2019, a different kind of haunted ship set out from the naval base on Haulbowline Island and sailed hesitantly up the River Lee. Strange, soulful music radiated from its top deck and out across the waters and shores of Cork Harbour. It appeared to be carrying a sole passenger – a figure wrapped in a sparkling foil blanket sat huddled against the grey steel. Below deck and out of sight, a human heart in a lead box was being returned to the place from which it had been stolen over 150 years ago. On a quayside in the city, a crowd had gathered to meet it.

Dorothy Cross isn’t resistant to Heartship being called a sequel to Ghost Ship, though the two-decade anniversary is a coincidence. Mary Hickson, director of Cork’s Sounds from a Safe Harbour Festival, first approached her with the offer of the use of a naval ship in 2017, and the project had been planned for last year. “It has not been smooth,” Cross says. I meet the artist the morning after the event. She is in exuberant form, if not a little overwhelmed. Now that Heartship has finally been realised, Cross is keen to praise the hard work of Hickson, as well as the foresight of Captain Brian Fitzgerald of the Irish Navy, but she also despairs of “the calcification of imagination” that she encountered repeatedly along the way.

“I think of the project in terms of an isosceles triangle…” Cross says, “… the heart, the voice and then the ship as a container, a reliquary – this vessel which is about both protection and destruction.” The voice is that of Lisa Hannigan and the song, Prayer for the Dying, is drawn from her 2016 album, ‘At Swim’, though it has been rearranged, pared-back and coupled with the music of Alasdair Malloy playing the glass armonica. Cross knew she wanted music that “originated from water” and she had already worked with Malloy on her ‘jellyfish films’. As soon as she heard Hannigan’s song, with its agonising refrain of my heart / your heart, she was besotted – “… it just seemed to sum up everything I was trying to do.”

The stolen heart is a remarkable object – a blob of wizened, colourless gristle which has been nestled in tissue paper and encased in a lead box in the battered shape of a heart. It might be as much as five-hundred years old, but nothing is known of its owner, nor of the circumstances which led to its being placed in the crypt of what was once Christchurch and is now the Triskel Arts Centre. It was discovered in 1863 and later acquired by General Pitt Rivers – an English officer, ethnologist and archaeologist whose collection of artefacts ended up in the University of Oxford. Cross had first encountered the heart in an exhibition in the Wellcome Trust in London in 2007. “It’s been in my consciousness for a long time…” she says, “… that the last heart I might work with would be human, after the snakes, and then the shark.” But securing permission to borrow it was the main source of the project’s delay and she found herself exploring other options: “I contacted all of the universities where hundreds of hearts languish on shelves; I spoke to surgeons about maybe getting a diseased heart which had been taken out in a transplant. I knew I was dealing with sensitive territory, but at the same time it was with such great respect that we were going to be treating the organ.” She went back, again and again, to pursue the Christchurch heart specifically because of its origin, and her tenacity, in time, paid off.

The anonymous, Corkonian heart finally sailed home to its harbour. “Part of me wanted to take it and throw it in the River Lee…” Cross says, “… and its lead box would draw it right down to all the silt and rubbish on the bottom and that would be the end.” Instead it disembarked, safely, in the sunshine to a military salute. “There was no attempt at any point to theatricise the process. I didn’t want any fireworks or fakery, but only what the navy would normally do – their own daily rituals and theatrics.” The heart was taken directly to a glass case in The Glucksman, while simultaneously in Crawford Art Gallery, a short film (also entitled Heartship and made in collaboration with Alan Gilsenen) played on a loop in a darkened lecture hall.

Cross is still surprised that the film came together in time for the festival. “In my head,” she says, “it had become too complex, but Alan had the faith that I lacked at that point.” The film is elegant and understated. A wind-buffeted Hannigan roams the decks, the camera following her but also wandering off, settling momentarily on the metal-ware and military equipment, panning across the ashen horizon. “We just went out into the harbour one day, as the navy did their routine manoeuvres,” Cross says. “At first I was afraid of Lisa’s beauty in a funny way – afraid that it would take away the essence of the project and turn it into a pop video. But I didn’t want to bring in the notion of the refugee too much either, to dress her in something which would suggest that. Essentially, I wanted to neutralise Lisa – to just have her voice as much as possible – the heart as the heart; the ship as the ship and Lisa as the energetic conduit between the whole thing, and that was what Alan managed to create.”

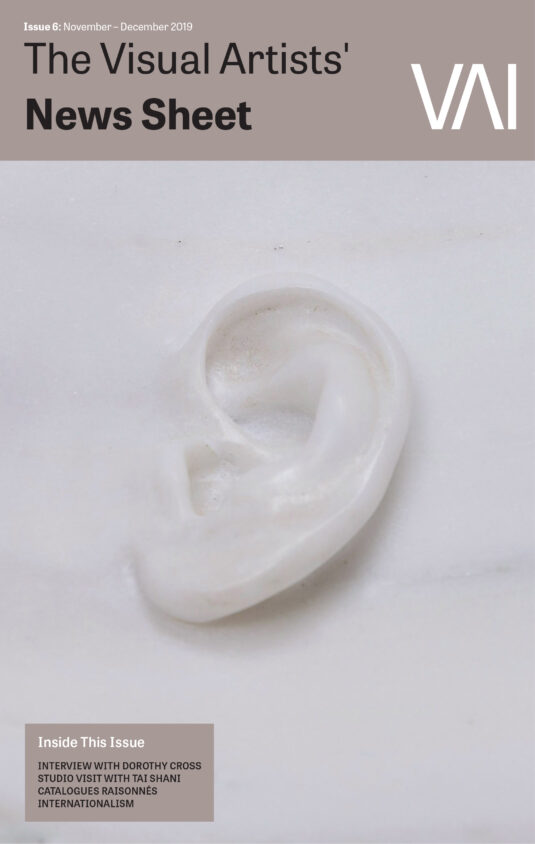

In spite of its understatement, it’s impossible to watch these scenes without calling to mind the Irish navy’s humanitarian role in the Mediterranean migrant crisis. When I ask the artist about politics, she speaks instead about her exhibition at Dublin’s Kerlin Gallery, ‘I dreamt I dwelt’ (6 September – 19 October). “It’s very much about human presence on the planet…” she insists, “… about demise and decay; time and extinction.” The exhibition presented three significant new sculptures. Listen Listen comprises a pair of carved marble pillows with a right and a left ear rising, as if sprouting, out of their indented centres. ROOM – “as in the verb…” Cross explains, “to give room…” – is an expanse of marble floor from which a small shark emerges; its position makes it difficult to tell whether it is struggling to the surface or being dragged down. “And then the third piece is quartz stones found on the beach which have been rolled by the water over centuries. Twenty-six of them have been carved with the letters of the Roman alphabet. It’s our language just thrown – scattered.” The artist’s choice of material is intrinsic to the meaning of the exhibition. “Marble should be humble and organic, but it has been glorified throughout history. There’s something unifying in its nature; there’s lots of subtraction but absolutely no addition; there’s the purity of it but also – it is so connected to death. Marble is both the tomb and the domestic dwelling; this is where the title comes from.” The title is from a line in a popular 19th-century aria: I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls, with vassals and serfs at my side. The line, like the exhibition, is full of darkness and longing.

On show concurrently at the Irish Museum Modern Art is another new marble sculpture by Cross, Everest Erratic, in the group exhibition, ‘Desire: A Revision from the 20th Century to the Digital Age’ (21 September 2019 – 22 March 2020). Speaking of this new work, she states: “I wanted to make a thing which was like a glacial erratic – a miniature representation of the pinnacle of our planet, which for most people is inaccessible, and yet at the same time, recently we’ve watched people queuing up to climb Mount Everest as if they were just waiting for a bus.” This kind of stirring contradiction has often been at the core of Cross’s work – her ability to marry elements which seem, at first, to be at odds has never waned throughout her career, now spanning thirty years. Each new work falls effortlessly into a continuum – branching from the last and stretching on – and yet when I ask her the dreaded question “what’s next?” she winces and insists that “… Heartship does feel like a bit of an ending. How can you ever get anything more powerful than those three elements? You can’t go past a human heart. It’s the essence of everything.”

After our interview, she will go to The Glucksman and visit the stolen heart before driving back to Connemara. “Heartship is gone now…” she says, “… it’s never going to be seen again. Maybe it just becomes narrative.” Maybe, in twenty years, people will still be telling the story of how they were there on the quayside in Cork harbour on a sunlit autumn day, as a haunted ship sailed up.

Sara Baume is a writer based in West Cork.

Based in Connemara, Dorothy Cross is one of Ireland’s leading contemporary artists. She is represented by Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Heartship was presented as part of the biennale festival, Sounds from a Safe Harbour (10 – 15 September 2019). Heartship was made possible through support from Cork City Council, The Irish Naval Service, The Glucksman, UCC, Crawford Art Gallery and participating artists.

Feature Image:

Heart (unknown origin); image courtesy of General Pitt Rivers Museum.