ALICE BUTLER PROVIDES A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY IRISH MOVING IMAGE PRACTICE.

It is difficult to appreciate the volume and diversity of contemporary practice in artist moving image and experimental film in Ireland without taking stock of its comparatively short history and modest origins. When artists and filmmakers in Europe, the UK and America – such as Germaine Dulac, Len Lye and Maya Deren – began experimenting with new possibilities for cinema as an artform in the early part of the twentieth century, they were also laying the groundwork for the foundation in the 1960s and ‘70s of the cooperatives and distributors (including the London Film-Makers’ Co-Op, the Film-Makers’ Cooperative in New York and Canyon Cinema in San Francisco) that would build indigenous collections and, in most cases, continue to disseminate artist moving image and experimental film material right up to the present day.

Without the formation of a robust native film culture until later than these international counterparts, Ireland did not follow the same trajectory. It was not until the 1970s and ‘80s that Irish artists and filmmakers began jointly to make moving image work for the gallery and cinema that challenged norms, both formally and politically, and much of this compelling early material – by artists like James Coleman, Vivienne Dick and ‘First Wave’ filmmakers Thaddeus O’Sullivan and Pat Murphy – was at least initially produced abroad. As a direct consequence of this new approach to filmmaking however, lasting infrastructural change – both for artist and commercial cinema – did come about in Ireland at this time. In 1973, the Arts Council of Ireland added film to the list of artforms that it supported, and in 1981 the Irish Film Board was established, becoming the country’s first state funding agency for cinema.

In the years since, there have been clear indications of the increasingly prominent role played by the moving image in Irish visual culture. As Maeve Connolly has pointed out, Irish artist moving image work has gained greater “visibility and legitimacy” since the 1990s, a fact illustrated, she highlights, by its recurring presence at the São Paulo Biennial (Alanna O’Kelly in 1996, Clare Langan in 2002, Desperate Optimists in 2004) and the Venice Biennale (Jaki Irvine in 1997, Anne Tallentire in 1999, Grace Weir and Siobhán Hapaska in 2001, Gerard Byrne in 2007, Kennedy Browne in 2009 and Jesse Jones in 2017).1 This same period has also seen a surge in the presentation of artist and experimental film material in Ireland in a cinema context, through a range of platforms including Darklight Festival, the Experimental Film Club and, more recently, the Experimental Film Society, PLASTIK Festival of Artists’ Moving Image and aemi. These diverse initiatives have emerged at least partly in response to the marked rise in production of this material in Ireland in the last twenty or thirty years, a development that mirrors international trends but is all the more striking in an Irish context, given how quickly the scene has evolved.

Because of the pace with which work of this nature has been produced here in a short amount of time, it is all the more pressing to underpin these practices with the resources afforded to artists, students, curators and researchers elsewhere, through organisations like LUX and REWIND in the UK, Lightcone and Collectif Jeune Cinéma in France, Arsenal in Germany, Auguste Orts in Belgium, CFMDC in Canada and many others. In an effort to address at least some of these needs in the first instance, Daniel Fitzpatrick and I founded aemi at the beginning of 2016, an organisation now funded by the Arts Council that supports, advocates for and regularly exhibits moving image work by artists and experimental filmmakers, primarily in a cinema context.

Aemi is one facet of a dynamic, shared ecology of artist and experimental moving image culture in Ireland. Through partnerships and collaborations (with festivals, artists, programmers and other arts organisations) we are keen to strengthen and contribute to a wider, broader infrastructure that is interconnected and mutually enriching. We also recognise that there is a thriving international network and circuit of activity around artist and experimental moving image practice that Ireland-based moving image artists and experimental filmmakers have not historically been in a strong position to engage with. This is not only because we are an island on the periphery of Europe but also because advocates or agents for Irish practice have been in shorter supply. In an effort to upend this frustrating trend, we frequently think about programming as an innate part of our role as a resource organisation. At our screening events, we regularly situate international work alongside films by Irish artists including Vivienne Dick, Sarah Browne, Susan MacWilliam, Saoirse Wall, Moira Tierney, Julie Murray, Aisling McCoy, Tamsin Snow, Alice Rekab, Vanessa Daws and Cliona Harmey. We also invite international curators, programmers and artists to Dublin to present their work in person, while giving them first-hand experience of the busy and diverse scene here. Guests we have previously welcomed include curators Herb Shellenberger, Benjamin Cook and Peter Taylor and artists Mark Leckey, Soda_Jerk, Anne-Marie Copestake, William Raban, Peggy Ahwesh, Lewis Klahr, Tamara Henderson and Sven Augustijnen.

Because it is relatively difficult for Irish artists to gain the same exposure as artists based in the main cultural hubs of Europe or the UK (by virtue of being en route for the stream of arts professionals constantly passing through), we have made a priority of touring aemi programmes abroad, so that we’re not just seeing some of the excellent work that’s being made here ourselves, but also sharing it as much as possible with international audiences. Thanks to funding we have been able to tour aemi programmes abroad for the first time this year, something which forms part of a larger initiative through which we have commissioned two screening programmes, curated and including work by Irish artists Sarah Browne and Vivienne Dick, that we are currently bringing to arts centres and cinemas around Ireland. Aemi is increasing audiences for and critical engagement with this material, through the collective experience of the cinema event, not just in Dublin (where until this year almost all of our screening events had taken place) but around the country more broadly.

The desire to foster a sense of community around this work also informs how we approach the aemi newsletter, which we send out by email to our subscribers every month, highlighting not only events that we are presenting but also festival submission dates, exhibitions and screenings taking place across the country. Signing up for the newsletter is the first step in our aemi affiliate programme which provides Ireland-based moving image artists with access to our free one-to-one advisory sessions, through which we offer feedback or advice around work-in-progress, new work or exhibition strategy. The affiliate programme will develop further in 2020, with the introduction of a regular series of aemi ‘Rough Cut’ events, where artists will also have the opportunity to present newly finished work or work-in-progress to a small group of peers as well as an invited producer, critic, curator or academic who will moderate the event.

Working on aemi has meant that I have had the privilege of viewing a wide range of artist and experimental moving image work produced in Ireland in recent years and this has informed a number of projects and screenings that I have curated in an independent capacity. While the artists I’ve worked with represent just a fraction of what is being made here at present, to some extent they offer insights into the varied landscape of contemporary Irish artist and experimental moving image practice. In autumn 2018, I curated ‘The L-Shape’, an exhibition featuring a new presentation of Going to the Mountain (2015) by Jenny Brady and The Invisible Limb (2014) by Sarah Browne – two moving image works that offered portraits of radically different subjects. In Going to Mountain, Brady’s study of three pre-verbal babies, the viewer is given a perspective divested of sentimentality that provides instead the opportunity to tune into the infants’ physical gestures and movements, often reflected in mirrored surfaces and made to appear unfamiliar through the use of slow motion and syncopated editing. An equally absorbing process of defamiliarisation is also at work in Browne’s elegiac, The Invisible Limb, a film letter addressed to deceased German artist Charlotte Posenenske that considers her work and enigmatic withdrawal from practice as a sculptor in 1968, in relation to Irish stone carver Cynthia Moran, an artist with a very different trajectory whom, it transpires, was born the same year as Posenenske.

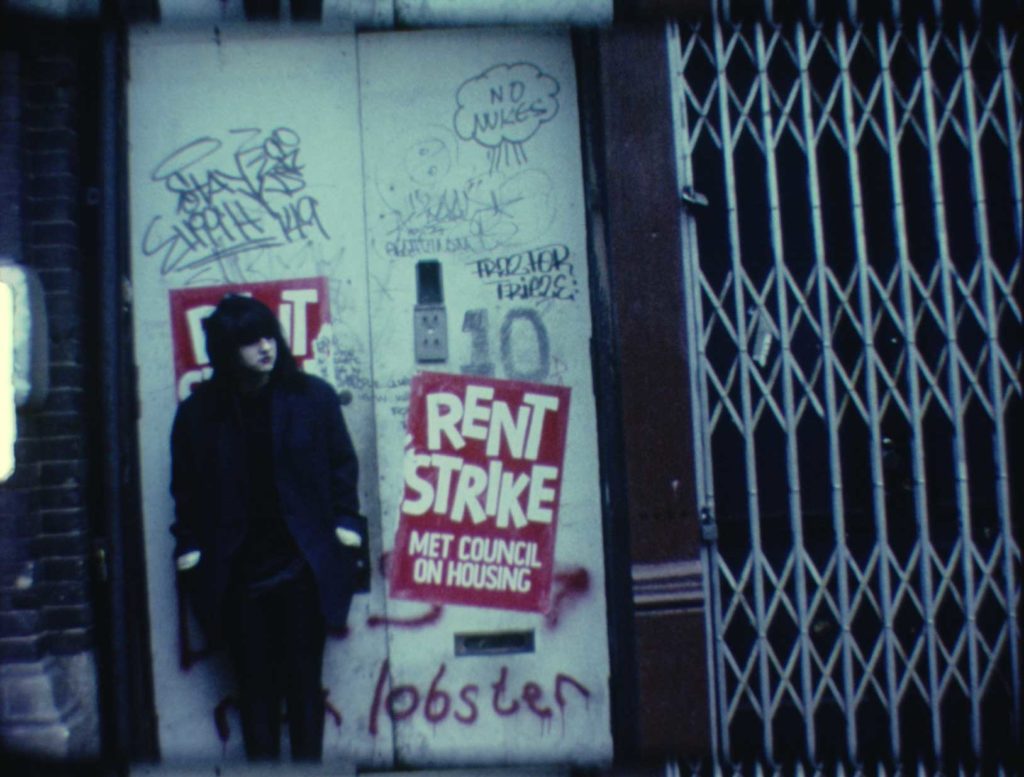

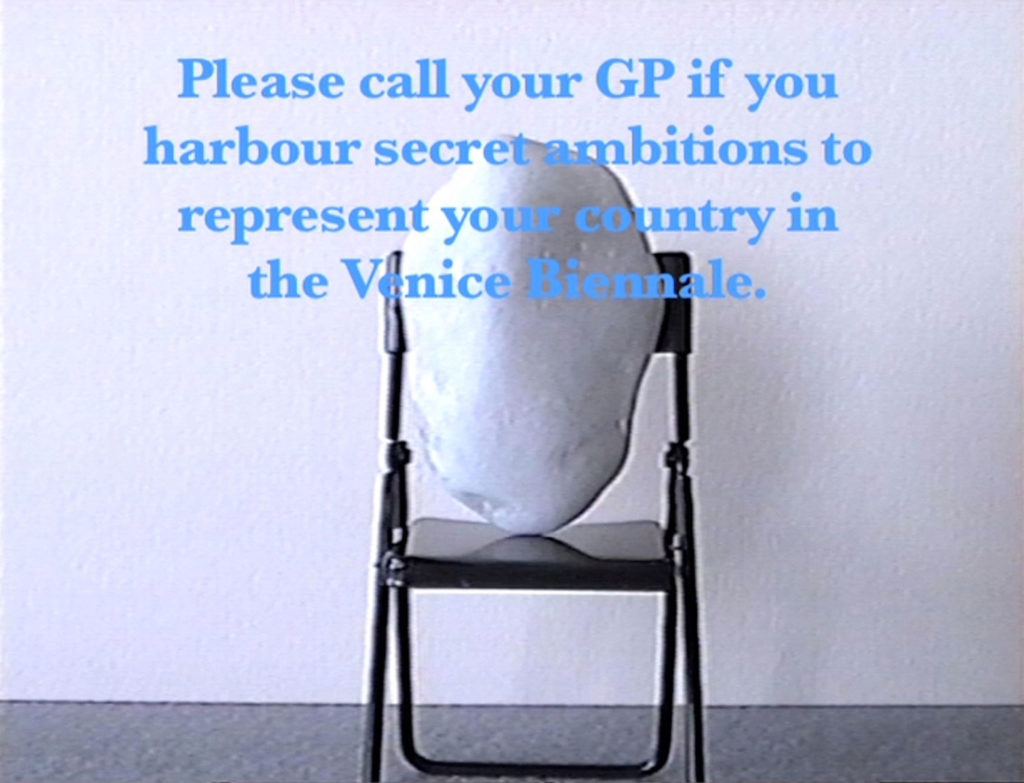

The uniquely challenging existence of the artist is also a concern in Laura Fitzgerald’s tragicomic Portrait of a Stone (2018). This was one of the films included in ‘Between Structure and Agency’, a screening of Irish work I curated last year for the Irish Film Institute and Culture Ireland, that will tour the UK with LUX. Fitzgerald’s split screen video piece contrasts footage of her father shot in his native Kerry, obligingly taking direction from his daughter behind the camera, with a steady flow of often humorous on-screen text in which the viewer is addressed as a presumed artist and presented with a multiple choice questionnaire in which every option spelt out is more ludicrous and desperate than the last. Also featured in the ‘Between Structure and Agency’ programme was Doireann O’Malley’s A Dream of Becoming 24 Eyes, 4 Parallel Brains and 360° Vision, a film that reveals a similar level of intimacy and vulnerability as explored in Fitzgerald’s video work, albeit in an altogether different tone. Shot on Super 8 and 16mm film, and drawing on material from the artist’s personal archive, the title references the anatomy of the box jellyfish and expresses, as O’Malley recently described in an interview for Vdrome, “the faint hope or dream of transcending the limits of human embodiment and perception”.2 Likewise Bea McMahon’s sublime silent 8mm Film of Octopuses (2013) – which featured in a screening I presented at the IFI in 2017, entitled ‘As We May Think’ – uses the camera to offer or imagine a vision not of an octopus, but instead an impression of what an octopus might perceive. These contemporary Irish film works then each demonstrate an impressive culture of practice that is experimental, both technically and conceptually – a culture that is deeply rewarding to engage with, as a programmer and film curator, and deserving of wider attention.

Alice Butler is a film curator, writer and co-director of aemi, a Dublin-based, Arts Council-funded organisation that supports and regularly exhibits moving image work by artists and experimental filmmakers.

Notes

1 Maeve Connolly, ‘Archiving Irish and British Artists’ Video: A Conversation between Maeve Connolly and REWIND researchers Stephen Partridge and Adam Lockhart’, MIRAJ 5.1&2, 2016, p.208. See: maeveconnolly.net

2 Doireann O’Malley in conversation about A Dream of Becoming 24 Eyes, 4 Parallel Brains and 360° Vision for the online exhibition platform, Vdrome. See: vdrome.org/doireann-omalley

Feature Image: Doireann O’Malley, A Dream of Becoming 24 Eyes, 4 Parallel Brains and 360° Vision, 2013, Super 8 and 16mm transferred to video, stereo sound; video still courtesy of the artist.