The closing event for ‘Eva 2016: Still (the) Barbarians’ was the culmination of one the most well received Eva exhibitions in recent years. Reflecting the scope and complexity of the biennial itself, the presentations and discussions were diverse and ambitious, representing a range of both Irish and international offerings on postcolonial discourse. Curator Koyo Kouoh began by introducing Alan Phelan’s “counterfactual” film Our Kind (2016), which imagines a future for Roger Casement had he not been executed in 1916.

Post-Colony: Curatorial Perspectives from India and South America

Chair Declan Long (MA Art in the Contemporary World, NCAD) reiterated Casement’s relevance to discussions on colonialism and postcolonialism in Ireland. His work in the Congo, Long stated, highlighted the abuses of colonialism and ties in to contemporary representations of exploitation, such as Jeremy Hutchinson’s work for Eva on indigo production.

Grant Watson (Curatorial Theory, Royal College of Art, London) has spent over 15 years researching and curating contemporary Indian art. Watson spoke mostly about the role of poet and artist Rabindranath Tagore’s art school Kala Bhavana, established in 1940, during the Indian decolonisation movement. In creating a syllabus for the school, Tagore and the artist Nandalal Bose wanted to bypass British influence, looking to the far reaches of Asia, as well as Europe, to create a cosmopolitan knowledge base for students. They travelled widely, including several times to Japan, bringing back books and ideas.

Watson noted Kala Bhavana’s connection to Bauhaus, which was established in the same year, and also emphasised the workshop and the social function of art. In both institutions the language of modernism was used to depict social upheaval, exploring ideas of colonialism.

Watson then spoke about his own curatorial practice, specifically his work with Sheela Gowda, whose large scale installations explore the problems inherent in the language of modernism as well as exploitation in modern India.

Independent curator and writer Catalina Lozano introduced her research and curatorial practice on forms of colonialism across Latin America. Her interest lies in historiography as a way to counter historical hegemonies. She introduced the theorist Anibal Quijano’s ‘coloniality of power’, which describes the continuation of colonial hierarchies and paradigms in postcolonial societies.

Lozano discussed several Latin American artists, beginning with Fernando Palma Rodriguez, whose works relate to his heritage in the indigenous central regions of Mexico. Palma Rodriguez explores the loss of minority languages and in turn of “particular and specific ways of understanding the world”.

Next, Lozano introduced Carolina Caycedo, whose work incorporates direct activism opposing the construction of multiple dams in Colombia, which has led to displacement of indigenous people and exploitation of natural resources. Continuing the theme of environmental concerns and of political protest, Lozano moved on to Eduardo Abaroa, whose work The Total Destruction of the National Museum of Anthropology (2013) imagines razing the Mexico City institution. The piece highlights inequality in how we regard artefacts, people and the natural world.

Next, Lozano introduced Carolina Caycedo, whose work incorporates direct activism opposing the construction of multiple dams in Colombia, which has led to displacement of indigenous people and exploitation of natural resources. Continuing the theme of environmental concerns and of political protest, Lozano moved on to Eduardo Abaroa, whose work The Total Destruction of the National Museum of Anthropology (2013) imagines razing the Mexico City institution. The piece highlights inequality in how we regard artefacts, people and the natural world.

During the panel discussion, Kouoh reiterated the idea of colonial constructs, arguing that discriminatory racial hierarchies, in particular, are an “invention of Europe”. For Lozano, this is an example of “internalised colonialism”, perpetuated by our continuing Eurocentrism.

Kouoh brought up assimilation and perpetrators becoming ‘local’, bringing the discussion towards Ireland. Lozano cited the mass extermination of indigenous people in Argentina, which occurred after the country’s independence, as an example of how indigenous movements are often in opposition to the mainstream anti-colonial agenda.

The discussion moved to the role of contemporary political and economic systems in continuing colonial structures. The ideology of neoliberalism, which sees capitalism as inevitable, Lozano argued, continues to posit indigenous people as “behind” in the model of social development. This was also explored by Tagore, Watson stated, in his attempts to create a different modernism not intrinsically tied to European industrial capitalism. In this system indigenous people are often “trapped by the idea of authenticity”, which defines them as worthy of protection but can also force them to remain stuck in a particular time.

Artists and Post-Colonial Legacy

Following a performance of Media Minerals by David Blandy and Larry Achiampong, artist Yong Sun Gullach spoke about her performance work on transnational adoption. Born in Korea, Gullach was adopted to Denmark. She sees transnational adoption as a continuing visible trace of colonialism and began by posing a series of questions challenging our preconceived notions: “Why do so many women have to give up their children? Why is this practice largely funded by receiver countries? Where are the parents in this process?”

In a particularly powerful description she referred to the process of transnational adoption as one of “exploiting resources” in a colonised country that contravenes the UN Declaration on the Rights of the Child by denying the child knowledge of their indigenous identity and their original family. The common practice of forging birth documents to comply with international rules further entrenches this. In the process of transnational adoption, whiteness is “borne upon” the child. A key part of colonialism, she argued, is that the norms of indigenous people in colonised countries become disorientated and are forced into Western paradigms, echoing Lozano’s sentiment about internalised colonialism.

Gullach emphasised the political potential of performance. Bodies possess the power to “define new linear norms” through processes of disorientation. She sees this as a challenge to postcolonial power that has not proved a popular position to assert within the art world.

Mary Evans spoke about her work and her life, which, like Galluch, are closely intertwined. Born in Nigeria, Evans moved to London in the late 1960s aged six and is interested in issues of migration, psychogeography and race. She began with an anecdote about her first experience of institutional racism after being relatively sheltered growing up in a community of immigrants.

Evans spoke about her use of decorative arts as a foil for the content of the work. Ordinary brown paper is a recurring motif, demonstrated in Held (2013), displayed at Limerick City Gallery, which depicts refugees waiting in an endless line. Evans often uses materials from her childhood growing up among immigrants from former colonies, representing their attempts to absorb and mimic British culture.

Lastly, Evans introduced a residency she undertook at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens, looking at how the movement of tropical flora and fauna mirrored the movement of people from former colonies to Britain and the botanic garden as a manifestation of Victorian imperial Britain.

In the discussion, Kouoh noted the common theme of ‘othering’ across the artists’ works. She questioned Achiampong and Blandy about the element of their work that encourages those around them to relive past events. Achiampong described how his own family never discussed coming to Britain as paperless migrants. Evans spoke of the common experience of Irish and West Indian immigrants in London, while Achiampong and Blandy emphasised the ways in which both similarity and difference of experience had brought them together. Achiampong talked of the shame felt by all migrants to a new country, his own childhood desire to be white and feeling different from his parents. This led back to Gullach’s thesis about the experience of transnational adoptees, whose history has been “whitewashed”. She became frustrated with official channels and activism, where she was often silenced for being “too emotional”. Mary Evans concurred, describing how art helps her to understand a history of which she has no direct memory but which affects her daily life.

Asked about their connection to Ireland, Achiampong, Blandy and Evans all referred to their direct experience growing up in Kilburn, London, among a large Irish community. Gullach made comparisons to the Faroe Islands, former colonies of Denmark that have internalised Danish language and culture to an “irreversible extent”. She noted the different trajectories of ‘white’ colonies, when oppressor and oppressed cannot be distinguished by race.

Architecture and Memory

Dr John Logan (History, UL) spoke about the changing urban shape of Limerick City. He began by showing a map from 1633, when the city was divided in Englishtown and Irishtown, moving to the changes of the eighteenth century when Edward Sexton Perry owned most of the land that now makes up the city centre. This sudden move from the theoretical to the physical demonstrated the tangible legacy of colonial rule on the urban Irish landscape.

The consistency of the British colonial project was evidenced in the familial connections between landowners and administrators in Ireland and India. Plassey House, for example, now part of the university campus, was named after a British victory in India in which thousands were slaughtered. It was known by this name for many years with little thought to its origin.

He described the “funnel of deprivation” that formed through the city after independence, as the rich moved to the outskirts, Englishtown and Irishtown dissolving only in name. This was the case across many Irish towns and demonstrates the reality of continuing inequality. Logan spoke about the concept of “fabricated histories”, exemplified by the reclaiming of the old Englishtown and its cobbled streets for tourism. ‘Education’ is used as a defense for prioritising these areas over those in which people actually live.

Dr Aislinn O’Donnell (Philosophy, UL) spoke about “navigating colonial remains” through philosophy. She returned to Lozano’s concept of internalised colonial structures, noting how the past “speaks through us” in our language, for example in the myriad ways people describe Northern Ireland: the six counties, the north of Ireland or Ulster. In this way our implicit allegiances are given away.

Referencing the philosopher Enrique Dussel, she queried Ireland’s position within the paradigms of colonial and postcolonial analysis. “Who are the Irish? Where is Ireland? Is it located at the centre or the periphery?” Ireland is positioned as a “different kind” of colony, largely due to its white population. European philosophy sees itself as universal, which is an important part of Cavafy’s poem after which Eva 2016 was named. What might a ‘barbarian’ philosophy be like?

She spoke of the “underside” of modernity: the genocides that were not “anomalies of history” but a central part of the ‘modern’ world created through colonialism. This conquering ego still decides “who gets to speak”. O’Donnell returned to Northern Ireland, and our reluctance to speak about it due to a “volatile mixture” of political shame and willed ignorance. The situation reveals a collective responsibility that has not been met.

O’Donnell emphasised her frustration in trying to talk about colonialism, which is viewed as unfashionable or embarrassing. Primo Levi’s notion of the shame of being human describes our refusal to see the suffering in which we are complicit. As both participants in and subjects of colonial structures we are unwilling to admit our own othering impulses.

The panel discussion, chaired by Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith, turned quickly towards the direct provision system in Ireland and the “uncomfortable otherness” on our doorstep, which has taken the place of the Magdalene Laundries. O’Donnell concurred, referring to Homi Bhaba’s writings. What we mean when we say we’re opposed to colonialism, she argued, is in fact very complicated in the Irish context. We are not living in a post colonial or a post racist society. Some lives are valued more than others.

Professor Luke Gibbons (Irish Literary and Cultural Studies, NUI Maynooth) introduced his closing remarks with a quote from Finnegan’s Wake about the English being full stoppers and the Irish semi colonials, and spoke about the “choreography of coincidences” that are created through art. Gibbons noted the connection between Tagore’s school and Pádraig Pearse’s school in their attempts to transcend colonial educational paradigms. He also mentioned Tagore’s play The Post Office, said to have inspired the Rising in its depiction of the GPO as the symbol of colonial rule. Continuing the word play, he stated a need to rescue the word ‘post’ from its temporal meaning.

Returning to the idea of invented tradition, he argued that seeing these histories as invented is a misconception. The past is not fixed. In the revolution the avant garde’s role is to imagine the future, which the present must then catch up with. The Rising, for example, had no popular mandate at the time and was seen by many as elitist. Its mandate has come from the future, which partly explains the state’s continuing discomfort. For Gibbons, memory is made and remade, not passed on. Commemoration is itself part of the 1916 Rising, which was not one event but is a continuous history that changes with memory.

Gibbons closed on the idea of colonial universalism, which counters reality, where everything is grounded in the specific. We view art through our own contextual eyes. He referenced Mary Evans’s point that the spaces between us are in fact what bring us together. Differences are simply more interesting. Art and aesthetic appreciation are necessary for filling in the gaps between the ethical and the political.

Lily Power, Production Editor, Visual Artists Ireland

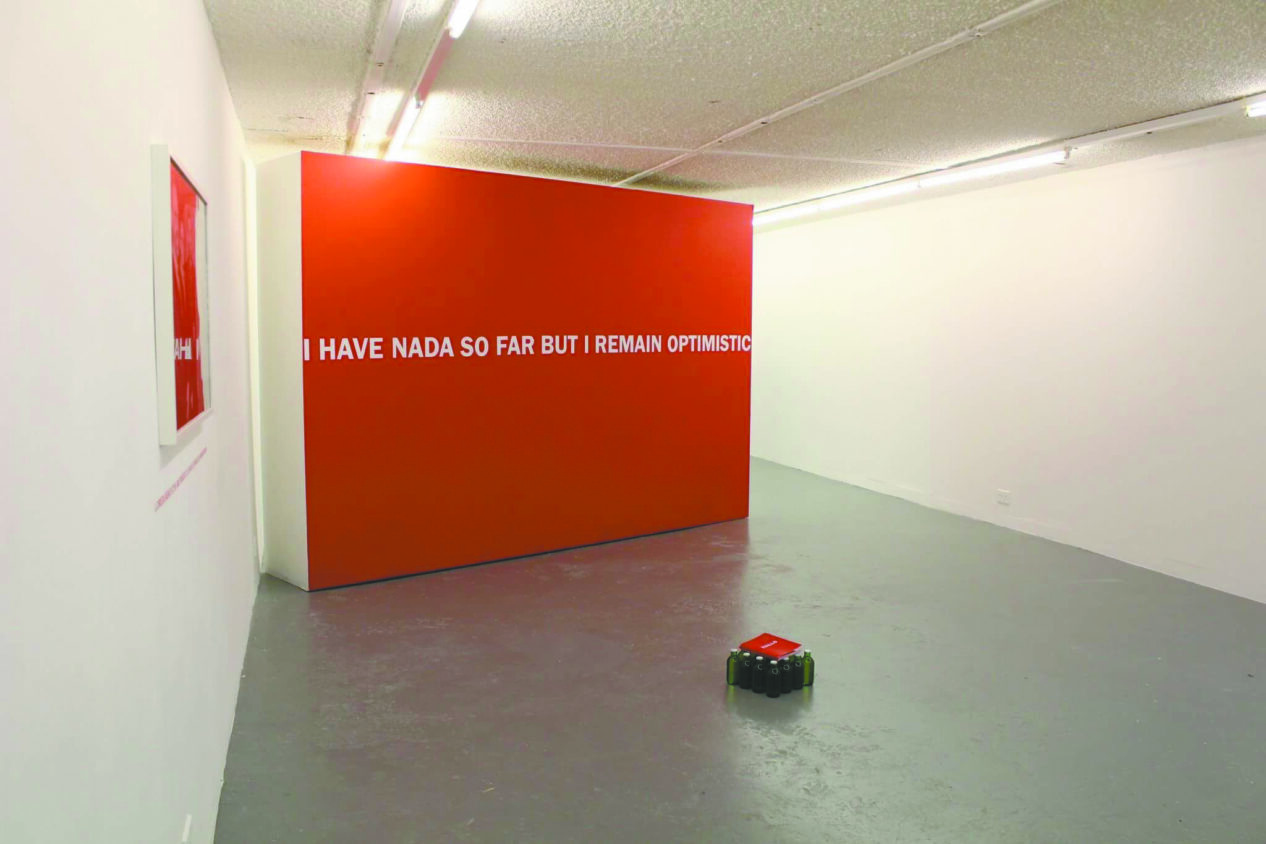

Images: Yong Sun Gullach performing at Eva; Koyo Kouoh and Larry Achiampong, Belltable, Limerick; photos by Deirdre Power